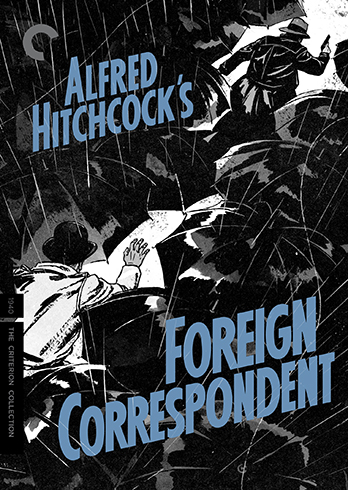

For the second winter in a row, the Criterion Collection has seen fit to add one of Alfred Hitchcock’s earlier (and presumably more easily licensed) titles to its lineup. Last January, the original 1934 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much provided a surprise to many of us who had no idea that it was even up for consideration as a Criterion release when it was first revealed. Though the announcement of Foreign Correspondent didn’t pack the same delightful wallop when the news was unveiled last fall (after all, the film had been available on Hulu Plus since 2011), Hitchcock aficionados should feel no less grateful to receive this lavish new edition of one of the director’s most pivotal works. Overshadowed nowadays by Hitch’s other 1940 film, his American debut Rebecca (which won the 1940 Academy Award for Best Picture and paired acting legends Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier), Foreign Correspondent (itself a Best Picture nominee) has to overcome the handicap of having less in the way of star power, a more dated and topical subject matter and a fairly tangled story line that doesn’t quite achieve the haunting emotional resonance that Rebecca‘s Gothic melodrama delivered to that film’s most ardent admirers. But as has been often observed by critics and is most readily evident to anyone familiar with Hitchcock’s work both in his earlier English films and those that followed this one, Foreign Correspondent is the movie that really established the director’s foothold in America. Much more than the heavy but enabling hand of Rebecca‘s producer David O. Selznick, the relative freedom afforded Hitchcock by producer Walter Wanger allowed the director to recreate the rapid pace of his British classics like The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes, incorporating the sly mix of racy/morbid humor and powerful visual and editing innovations that he would go one to perfect over the course of the next few decades.

Released in the fall of 1940, after Rebecca had already proved itself a sensationally successful follow-up for Selznick to Gone With the Wind, released the previous year, Foreign Correspondent took a consciously “ripped from the headlines” approach in updating the book Personal History, a newsman’s memoir from the mid-1930s. The American reporter Vincent Sheean had won the National Book Award of 1935 for his first-hand accounts of some of the major European political developments of the previous decade. That basic concept, of a fearless freelancer who somehow managed to get himself positioned as an eyewitness to history, is about the only element that carried over from the book to the movie adaptation. The rights had circulated for several years before they landed in Hitchcock’s ample lap, and his assignment from Wanger was to come up with a screenplay that put a journalist in the thick of the action as the Continent’s various principalities and powers trembled on the brink of imminent, inevitable war, which as everyone knew at the time had indeed broken out following Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939.

What Hitchcock and his collaborators came up with was a story involving Johnny Jones, a reckless street-beat scribe sent over to Europe so he could do some digging in places where better connected, more sensible professional journalists fear to tread. His assignment is to interview Van Meer, a senior diplomat who’s presumed to have inside knowledge on what’s about to happen as tensions escalate between the nations. But when he lands, Jones is immediately drawn into a vortex of obfuscation, betrayal and insidious posturing involving a pacifist front organization, double-agents and, of course, a beautiful young woman somehow oblivious to just how entangled she’s become in a web of danger and deceit. The stage is set for a thrilling mix of adventure and suspense, laced with acerbic wit and a sudden eruption of romance that seems all but implausible until we learn (courtesy of James Naremore’s liner notes) that the impromptu ship deck marriage proposal that takes place shortly after the meeting of leads Joel McCrea and Laraine Day was based on Alfred Hitchcock’s offer of engagement to his future wife Alma. In keeping with the standard mystery fare of its era, the plot reversals are numerous, sometimes incredulous, and the clues can fly by rather quickly if one is not paying close attention. I wouldn’t put this narrative up at the top of the list of Hitchcock’s most ingenious constructions, but that’s a high standard in any case. Here, the proceedings develop with enough cleverness and subtlety to warrant future viewings, just to make sure we have the details sorted out good and proper.

In socio-political terms, the trick of making the film consisted in balancing the intentions of Foreign Correspondent‘s producer and director to mobilize the American populace into shaking off its apathy and isolationism toward the atrocities unfolding in Europe with a cautious conservatism that wanted to avoid taking any stands that would offend German business interests (as well as the American financiers and industrialists that sympathized with many of the aims of the fascist regimes of that era.) Thus viewers then and now wind up scratching their heads wondering what’s the point of references to the “Boravian ambassador” and other absurdly transparent veils that avoid mention of the Nazis outright (though Hitler gets a fairly neutralized name-check early on.) And for much of the film, the mobilization of public sentiments is hardly given any attention at all. As it should, the emphasis remains squarely on the swiftly unfolding action involving false identities, closely guarded secrets that would wreak havoc if they fell into the wrong hands, assassination attempts and that peculiarly consistent characteristic that runs through practically every Hitchcock film that comes to mind: the average guy who somehow finds himself caught up in extreme perils far beyond anything he bargained for in the course of just wanting to do his job.

But when that “call to action” is signaled, underscoring the urgent need to take sides in the war (on behalf of England and Western Europe, against the Axis tyrants), boy is it delivered with an unmissable sledge hammer, especially at the film’s end when the blanket of patriotic sentimentalism is laid on so thick and earnest that it’s hard to conceive Hitchcock had any say in the decision. (Indeed, the ending was tacked on just to drive home the pro-intervention, pro-England point.) No matter, really – it gives Foreign Correspondent a precise cultural time stamp and effectively puts us very much in the moment of the film’s original context. The attitudes and temperament of the war years also comes through clearly in bonus features focusing on “Hollywood Propaganda and World War II” and “Have You Heard,” an exhortation for readers to be careful and on the lookout for spies and saboteurs, told in still images that Hitchcock composed for publication in Life Magazine in 1942. We’re also treated to a 1946 radio play that condenses the story into less than an hour and stars Joseph Cotten in the lead role.

Beyond Foreign Correspondent‘s place in either Hitchcock’s canon or American film history, there’s a lot of pleasure to be found in the creative beauty and originality of this movie, especially in the set designs and special effects work. The production details are nicely covered in another new supplement included in Criterion’s release, taking us behind the scenes to learn how they made the famous Dutch windmill sequence, the pursuit of the assassin through the crowd of umbrellas, the reporter’s escape via the ledge of his hotel room and most remarkably the plane crash into the ocean, which remains utterly astounding almost 75 years after the scene was filmed. Rounding out the extras is an hour long 1972 interview with Hitchcock from The Dick Cavett Show where we not only get to listen in on quite a few of Hitch’s well-rehearsed reminiscences but also to get a sense of the chemistry between the venerable old curmudgeon and his fairly adoring audience. As much as the power and poignancy of the feature film itself, the conversation’s ability to capture Hitchcock’s charisma fairly late in life makes this generously appointed and handsomely illustrated package an essential acquisition for the great director’s legion of fans here in the USA and all around the world. With a few other older Hitch gems currently available on Hulu (Blackmail, Secret Agent and Sabotage), let’s hope this won’t be the last of his films to bear the Criterion logo and benefit from their immaculate presentation.