With a career spanning 50 years and over 30 feature films, legendary filmmaker Akira Kurosawa was an auteur all his very own. Best known for samurai epics like Seven Samurai, Kurosawa’s career featured ventures into noir (High and Low), crime drama (Rashomon) and even war epic (Dersu Uzala), but few of his films were as decidedly singular as one of his most grand and deeply personal works.

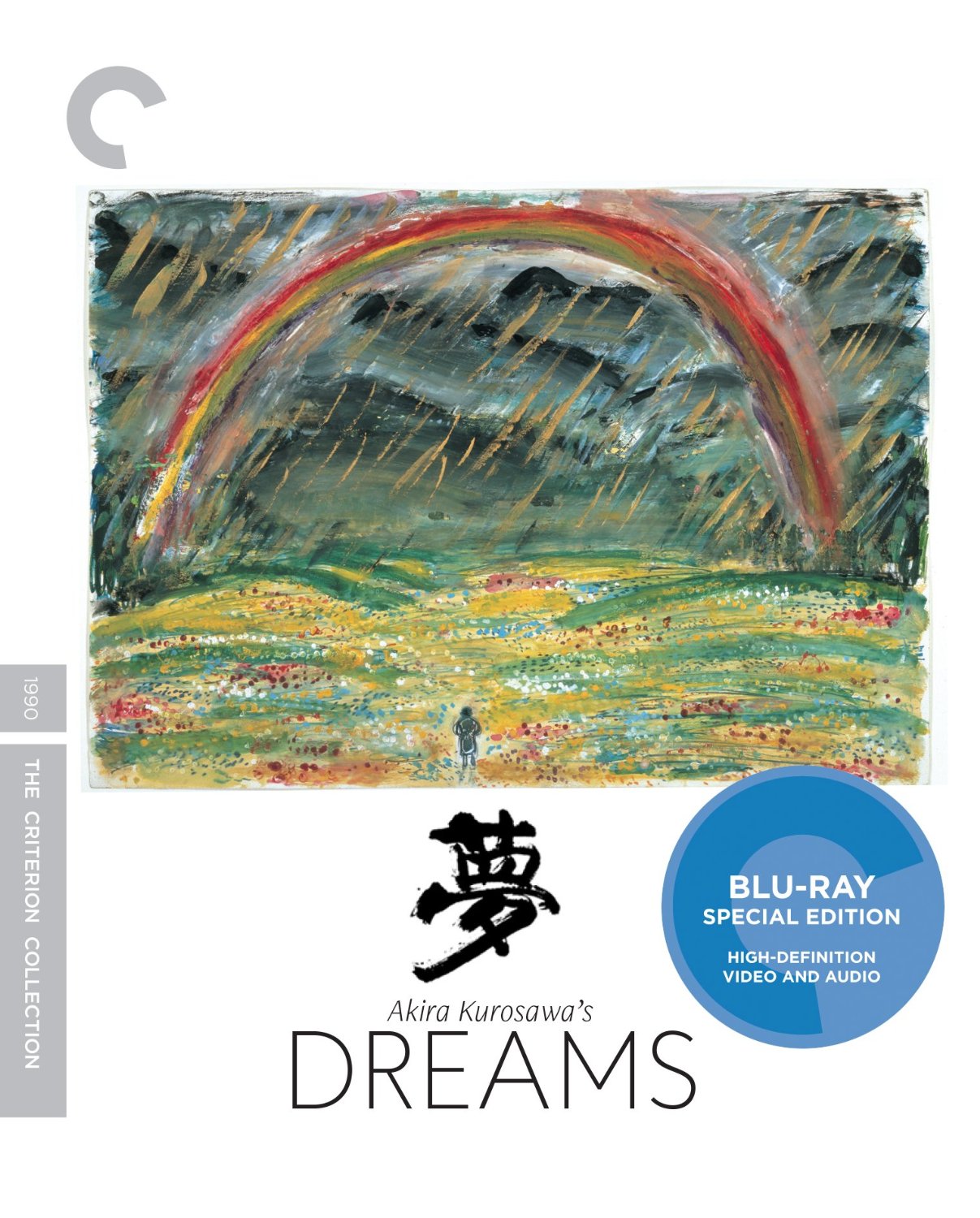

Entitled Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (at least how it’s billed on the Criterion Collection website), this sumptuous epic is admittedly an oddity in the Kurosawa canon. Narratively, the film is broken down into eight varied vignettes, all of which drawn directly from actual dreams had by the film’s director. Rooted heavily in Japanese culture and folklore, Dreams takes us from small scale stories like that of a young boy getting caught in the middle of a forest-set fox wedding, to the apocalyptic with that of a nuclear power plant near Mount Fuji and its meltdown. Toss in surreal ventures like a breathtaking ode to Vincent van Gogh (more on that Martin Scorsese-starring short in a moment) and nightmarish yarns involving ghost soldiers and a demonic mountain witch and you have one of Kurosawa’s most breathlessly crafted and bizarrely moving works, particularly from his underrated late period.

At first glance, viewers will and very much should be absolutely blown away by the film’s aesthetic experimentation. As noted in the new Criterion Collection Blu-ray’s commentary from film scholar Stephen Prince, throughout his career Kurosawa would experiment not only with things like wide lenses and slow motion footage, but particularly things like using framing as a narrative device of sorts and even how focus allows for a different dimensional quality within a frame. This is clear here as well, be it how flowers are framed in one of the film’s opening set pieces, to his striking use of focus in an orchard sequence just moments later. Arguably best known for his bombastic, still-influential samurai epics, Dreams is one of the director’s truly great aesthetic fetes, particularly in his ability to both give each segment their own stylistic flair, yet never lose the connective sense of inherent surrealism that comes with each story. Be it a relatively small scale piece like that of a soldier facing the embodiment of the repercussions of war or an almost Fantasia-like journey through, literally, the work of and a direct confrontation with Vincent van Gogh, the film never loses sight of the almost fairy-tale like nature of dreams and how it can be enhanced by cinema. Aided by fellow filmmaker Ishiro Honda in a handful of segments and given real life by all-time-great photography from dual cinematographers Takao Saito and Shoji Ueda, Kurosawa is at the very top of his directorial game here, giving nuance and a singular voice to a handful of emotional, thought provoking and utterly moving vignettes.

Throughout each segment the viewer follows a character named “I.” Seen throughout his life from child to adulthood, I is played by actors Akira Terao (man), Mitsunori Isaki (boy) and Taoshihiko Nakano (young child), and while much of the film tasks these actors with being passive characters, each gives a specific energy to the role. Terao is particularly of note as many of the vignettes involve his iteration of Kurosawa’s “I,” and his character (also known as The Dreamer) is quite intriguing. There’s little to no actual narrative connection between the vignettes, and while that may leave the viewer struggling to find a connection at two hours, each of these performances offers up just enough of a center for the viewer to truly latch onto. Hell, even Scorsese is great in an albeit small segment as Vincent van Gogh. The van Gogh segment is likely the film’s most notable both for the Scorsese cameo as well as the simply unforgettable visual style, which finds Terao’s character literally embarking on a journey through various works of the legendary painter. It’s a decidedly singular segment and a real tour de force from a filmmaker who always pushed aesthetic boundaries. However, the film’s strongest and most intellectually stimulating segment may be that of a soldier coming face to face with the ghost of a fallen soldier, as it speaks not only to Kurosawa’s deft hand at framing and classical framing, but also his own personal conflict with war and what truly comes of it. It’s a haunting set piece that’s simplistic in its setup but offers up some of Kurosawa’s most unshakeable images, particularly from this period in his career.

Long considered a “lock” for entry into The Criterion Collection, Dreams is now not only finally among the ranks, but in one of the company’s best 2016 releases. Putting aside the glorious new 4K digital transfer with involvement from DP Shoji Ueda and the crisp new audio master which helps elevate the sound design which was produced within an inch of its proverbial life, there are superb supplements abound here. As mentioned above the Prince commentary is a must-listen for fans of the film as well as first time viewers alike, and interviews with production manager Teruyo Nogami and assistant director Takashi Koizumi help give a glimpse into the process behind producing such a brazen piece of work like this. A 55-minute documentary comes as well, with Kurosawa’s longtime translator Catherine Cadou behind the camera, and filmmakers ranging from Bernardo Bertolucci to Hayao Miyazaki in front of it. Rounded out by a trailer and a booklet that includes a top notch essay from critic Bilge Ebiri and a script for a never-filmed ninth dream sequence, and you have a release that will leave fans of this film, new and old, mining it for days to come. Often overlooked due to its placement in the late, unsung period of Kurosawa’s career, this is as clear a cinematic statement as the director would make across his decades-spanning career. It’s also arguably one of his best films, and has never looked quite as good.