There are some tropes in pieces of fiction, medium be damned, that are absolutely time tested. In every romantic comedy, a boy or girl will meet a boy or girl only to lose this potential lover and ultimately win him or her back through a series of comedic and hopefully touching gestures. For every “last heist” there’s an aged former crook looking to get out of the gutter by returning to the world of crime in every other crime story. And for every bank job, there are a series of criminals that will undoubtedly fail to successfully steal the goods they have set their sights on.

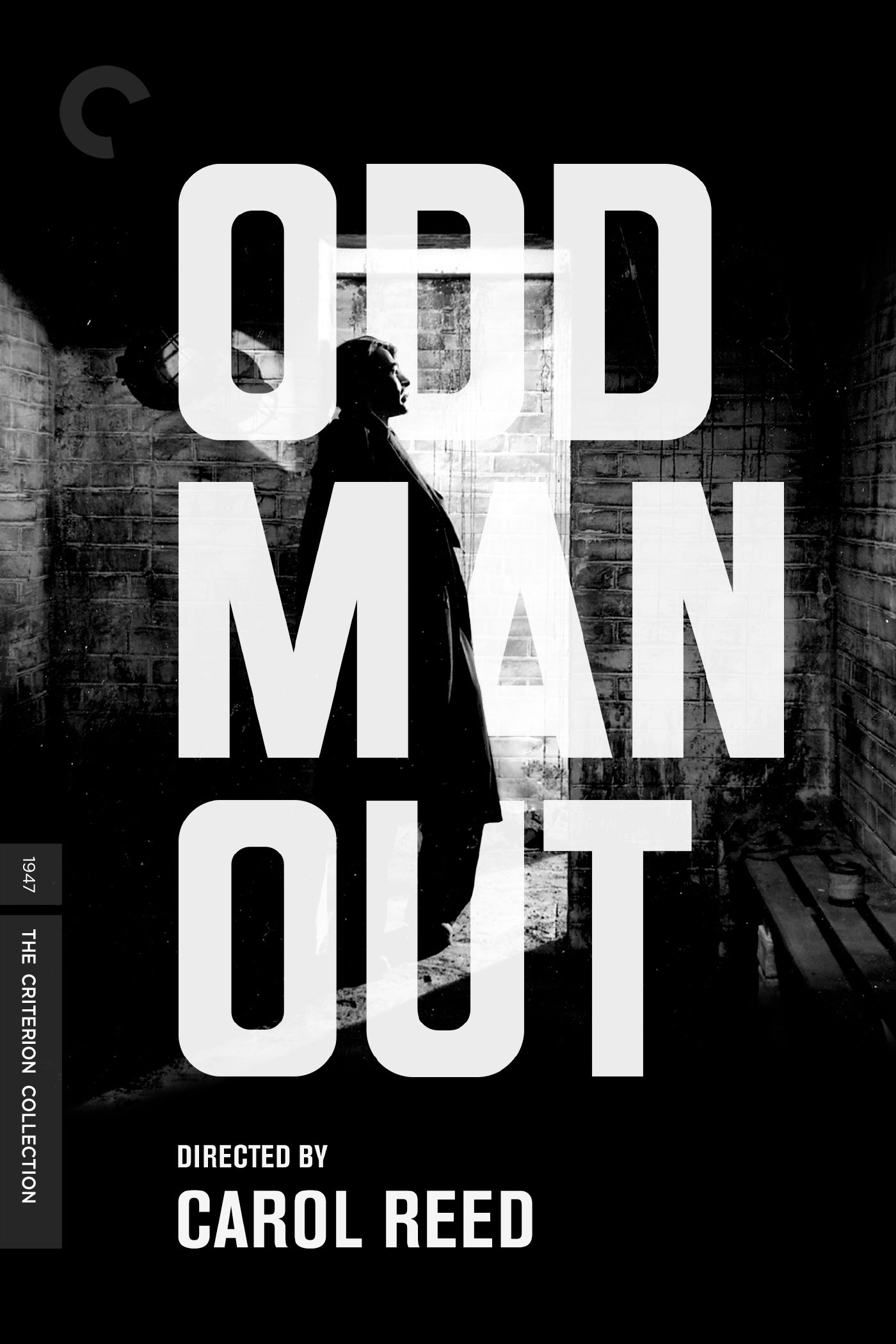

Now, while this type of paint-by-numbers narrative structure may be easy to read, there are some pieces of work that take these genre-specific tropes and turn them from cliche into groundbreaking brushstrokes that only give more vibrant color and detail to the pieces of art being crafted. Carol Reed’s legendary post-war noir Odd Man Out is exactly that type of motion picture.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqctI12CBzo

The first of three iconic noirs Reed would make following the end of World War II (capped off by The Fallen Idol and The Third Man), this would be a change of pace for not only its director, but also its star. Starring the ever magnetic James Mason, we are introduced to a proto-IRA leader (the group is never named, nor is the film’s location which is clearly Belfast) named Johnny McQueen who himself has been on the lamb following his escape from prison. Holed up in a house owned by a woman named Kathleen Sullivan (played by the breathtaking Kathleen Ryan) and her grandmother, he plans a heist that, despite his men’s displeasure in his current state following his escape, he ultimately goes out and leads forward. However, when things go sour, he is ultimately injured and after falling from his getaway car, is left only to go on the run again as he tries to last for as long as he can. Ostensibly told over one hectic night, the film is a relatively straight forward man-on-the-run noir that tells the tale of a man who hungers for some sort of salvation despite having killed a man in the heist, and the people he encounters. But the way it is told turns this into one of the many masterpieces the underrated Reed would craft during his career behind the camera.

Aesthetically the film is bewildering. Very much rooted in both the German Expressionism that would turn the noir genre into something entirely its own, as well as the poetic realism that had made the French cinema in the 1930s something of a golden age, the film is unlike any noir you’ll ever see. Made prior to a film like The Third Man, the film may not have the same unsettling camerawork that that picture has, but what this has is a distinctly melancholic sense of tone and atmosphere, and the black and white photography from Robert Krasker (who shot both The Third Man as well as David Lean’s masterpiece Brief Encounter) is startling. Noir, especially in the days so close to the end of WWII, is inherently a melancholic genre, as the existential angst rooted in almost every frame drenches the film in a sense of dread, that is only elevated with the poetic realism-like use of dream sequences that play throughout the film. Mason’s Johnny, while deeply passive, does go through a series of nightmarish encounters with various moments from his past, and these moments help elevate an otherwise notable, but relatively standard, noir film.

Odd Man Out’s main flaw is in its structure. While this type of story is interesting to see crafted in the genre of film noir, the fact that Mason’s lead is as passive as he truly is makes this film a hard one to find an emotional core to cling to. A passive lead in a noir film is an interesting concept, particularly as the genre’s existentialism influences are clear, the fact that his entire life depends on the reaction of these few men and women he runs into over this one night is hard to engage with. It becomes a structure that makes the film feel a bit longer than it actually is, and doesn’t give the performances the time or room to truly breath.

Thankfully, the performances are quite superb despite this odd structure. Mason turns in a performance that is unlike any he gave prior, or would truly give following. It’s a passive performance, granted, but it is one that has an energy to it that ultimately saves the film from being just a forgettable piece from a genre full of forgettable pictures. Kathleen Ryan is the film’s real beating heart however, as her love for Mason’s Johnny is undying and really gives a depth and a beauty to the proceedings. More an interesting tonal piece or thematic meditation than a real narrative-driven picture, Odd Man Out is a breathtakingly atmospheric look at one man’s journey inward that may be a tad repetitive structurally, but is saved and made all the more important by a director at the very height of his craft.

Criterion’s new Blu-ray release also helps give this film depth. Visually, the new restoration is glorious. The contrast heavy photography is given new life, and as hinted at in a separate supplement discussing it, the score from William Alwyn is both entirely unlike anything you’ll hear in a noir film, and also absolutely beautiful here. Scholar Jeff Smith muses about the score in a supplement, as does John Hill, who discusses the film’s history and its relation to Ireland. There’s a short documentary featuring various critics about the film itself that is a must-watch and important text when viewing the film, and a documentary from 1972 that features Mason revisiting his hometown. Toss in a radio adaptation of the story with Mason, and you have a release that is a must-own for noir fans and a worthwhile blind buy for anyone with a distinct appreciation for auteurs and works of aesthetic genius.