When looking at the entire medium of film from a respective region, very few areas on this planet have given the film world as naturalistic, quiet and pensive motion pictures as that of the world of African film. Ostensibly focused entirely on the battle between past, present and ultimately the future, African cinema has been deeply rooted in naturalism, taking the neo-realism from Italian cinema, and turning it into a vehicle for some rather entrancing discussions on generation gaps and the conflict between past, present and future.

And as one of Africa’s greatest films, Djibril Diop Mambety’s Touki Bouki, opens, one would envision the film following a typically naturalistic, faux-documentary aesthetic. Opening with herds of cattle walking through fields, only to be taken to a slaughter house where director Mambety unflinchingly shoots one’s execution, one thinks that what is set to follow is going to be a rather uncompromising look at the battle between history and modernization in Africa. That would be what one would think if they stopped watching, because as the film progresses, there is a pinch of that under the film’s surface, but this is as esoteric and experimental a film as the continent of Africa has ever given the cinematic landscape.

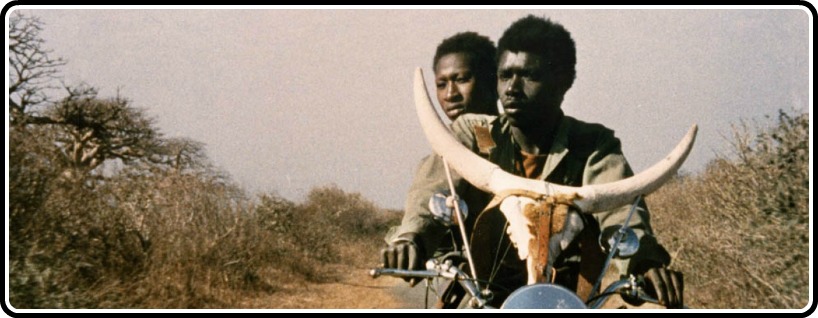

Touki Bouki tells the story of a young man who gets by by committing little crimes here and there in Dakar in the hopes of taking himself and his girlfriend to their dream land of Paris. Infused with the playfulness and anachronism of the French New Wave, Mambety’s film is a truly breathtaking debut film that is both an entrancing motion picture all its own, and yet a completely definitive African feature in its relationship to the people and the history of the nation it comes out of.

Coming out of Senegal, this film, first and foremost, is definitively African in its relationship to the history of the nation it comes from. A startling blend of African neo-realism and thoughtfulness and French New Wave anarchy, Touki Bouki, much like the former French colony that is Senegal, is a powerful blending of cultures, voices and energy. Released just 13 years after the country earned its freedom from France, Mambety’s film is arguably a influenced by names like Godard as it could ever imagine being by names like Sembene.

And in this energy, again inspired by the New Wave that launched the decade prior, the film becomes something truly special. Mambety is the star of this, his debut feature, and crafts one of the most auspicious debuts in all of film. Confounding in many ways, this stream-of-conscience-style picture, steeped in surrealism, is a beautiful look at two people hell bent on reaching their dreams. George Bracher is the cinematographer for this film, and it is truly unlike anything you’ll ever see. Especially in this new restoration from The World Cinema Project, the film’s grain pops right off the screen, particularly in the early sequences and those involving the more naturalistic beats the film has within its DNA. The “dream” sequences are an entirely different beast, with an anachronistic soundtrack and some wonderfully evocative imagery, often times brought upon by static cuts and some experimental use of editing. A completely singular aesthetic experience, particularly when taken as a part of the greater overall collective of films that is the African cinematic canon, Touki Bouki is a perfect blend of Rossellini style realism and some Godard playfulness and aesthetic anarchy.

Performances here, while great, do take a back seat. Both Magaye Niang and Mareme Niang are great here, but they play more broad characters than anything truly feeling of flesh and blood. Their dream of leaving their land for the dream of Paris is relatable and beyond vital, but the aesthetic here is so playful and continually moving that they seem to take a back seat. However, what doesn’t take a back seat is the esoteric musical choices here, and again the photography from Bracher, combined with Mambety’s direction, turns this into one of the greatest films to come out of the routinely underrated film canon of Africa.

Supplements on this part of the Criterion Collection’s World Cinema Project release are light, but entrancing. Touki Bouki comes with a gorgeous and energetic new digital restoration, which really adds even more life to this already vibrant picture. WCP founder Martin Scorsese gives a short intro to the film, and filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako gives an interview on the importance of the film to African cinema. It’s a solid watch, and plays its part as one sixth of this massive Criterion box set, one of the year’s best home video releases.