From, literally, the film’s opening title cards, Roma announces itself as something of a visual feast. A blood-red screen introduces us to the proceedings, with the four letters making up the Italian name for the nation’s capital of Rome fading in in all of their grand, pitch black glory. It’s a bombastic introduction to one of director Federico Fellini’s most esoteric and yet deeply personal motion pictures.

Also known in some circles as Fellini’s Roma, film critic Vincent Canby was right in suggesting that that specific title might be the real way we should look at this picture. While taking the title from the real capital city of Italy, this is not a Rome anyone recognizes at first glance. Seemingly a journey through the streets of a Rome from a universe just adjacent to ours, Fellini all but neglects anything truly resembling a coherent narrative, Roma is a tone poem of sorts, an autobiographical travelogue that resembles works of Gonzo journalism that would make names like Hunter S. Thompson icons in the US.

Fellini’s film is split across two real narratives, first introducing us to a young man (a Fellini proxy, if you will), who we first meet as he arrives in the city. Ostensibly the backbone of the film, it’s through this character and his uncertainty in the new city that we slowly become accustomed to the in many ways crude and vulgar nature of this cartoonish caricature of Rome. A city whose DNA runs rich with hedonistic pleasure, Rome is shown as an impressionistic, baroque city that is as grotesque in its lusty nature as it is utterly magnetic in its campiness. While Fellini embeds a documentary nature to a handful of scenes found within this specific narrative thread (particularly an eating sequence in the film’s first act), we never lose sight of the fact that this is Rome seen through the eyes of an outsider. Be it a cartoonish character design or a specific person staring directly into the camera, there is always an embracing of the artifice in this film, an artifice that sees this film evolve from a simple memoir into something far more experimental.

And with “what about the Rome of today,” Fellini jettisons us from the Rome of his youth, to the Rome of his then present. We meet a film crew in the throes of production, as they attempt to get to the core of what truly is the Rome “of today.” That’s about as structured as this film’s narrative truly gets. We go from a breathtaking sequence set in the middle of a bustling cityscape only to go below ground to see a group of people on an archeological as they uncover a hidden trove of art that’s gone in the blink of an eye, and even a baroque and utterly transfixing clergy fashion show, all turning this two hour long film into a scatterbrained and absolutely breathtaking bit of Fellinian tomfoolery.

Again, what makes Roma (like Amarcord, the other Fellini film this is most oft-compared to) a captivating piece of work is the filmmaker’s absolute control over his craft. While superficially the film seems absolutely lacking in any cogent narrative, it’s in actuality a very close kin to a film like Kurosawa’s Dreams. A series of tableaus ranging from the neo-realist to the almost defiantly surreal, Fellini’s voice is rarely more clear than here in this film. We see sequences like the opening involving a group of school children and a devolving lecture they’re witnessing; which itself, with its young boys and girls showing visible war wounds of their burgeoning creativity, is almost comical in its personal relationship to the filmmaker. And yet there are also moments like the above mentioned, perverse fashion show that makes up a good portion of the film’s back half, that’s as satirical in its discussion of The Church as the other sequence is personal. Where Kurosawa’s film is simply a collection of dreams had by the director, Roma feels just as personal, instead having the feel of a stream of one’s consciousness as they walk down the streets of a city remembered.

It’s also lushly composed. The photography here was done by famed cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno (All That Jazz), an oft-collaborator with Fellini. While the director is best known for his iconic black and white films, through films like Satyircon and Amarcord, Rotunno helped compose Fellini’s ornate color pictures, giving them an almost primal feel. The daytime sequences here are warm and inviting, and the nighttime compositions have an energy, with the production design helping to give a dream-like vitality to the proceedings. Rotunno’s work here is elaborate and justly baroque (word of the day, as it should be when talking about Fellini), giving the film an impressionistic color palette that helps evoke the “city remembered” feel the film so strongly tries to attain.

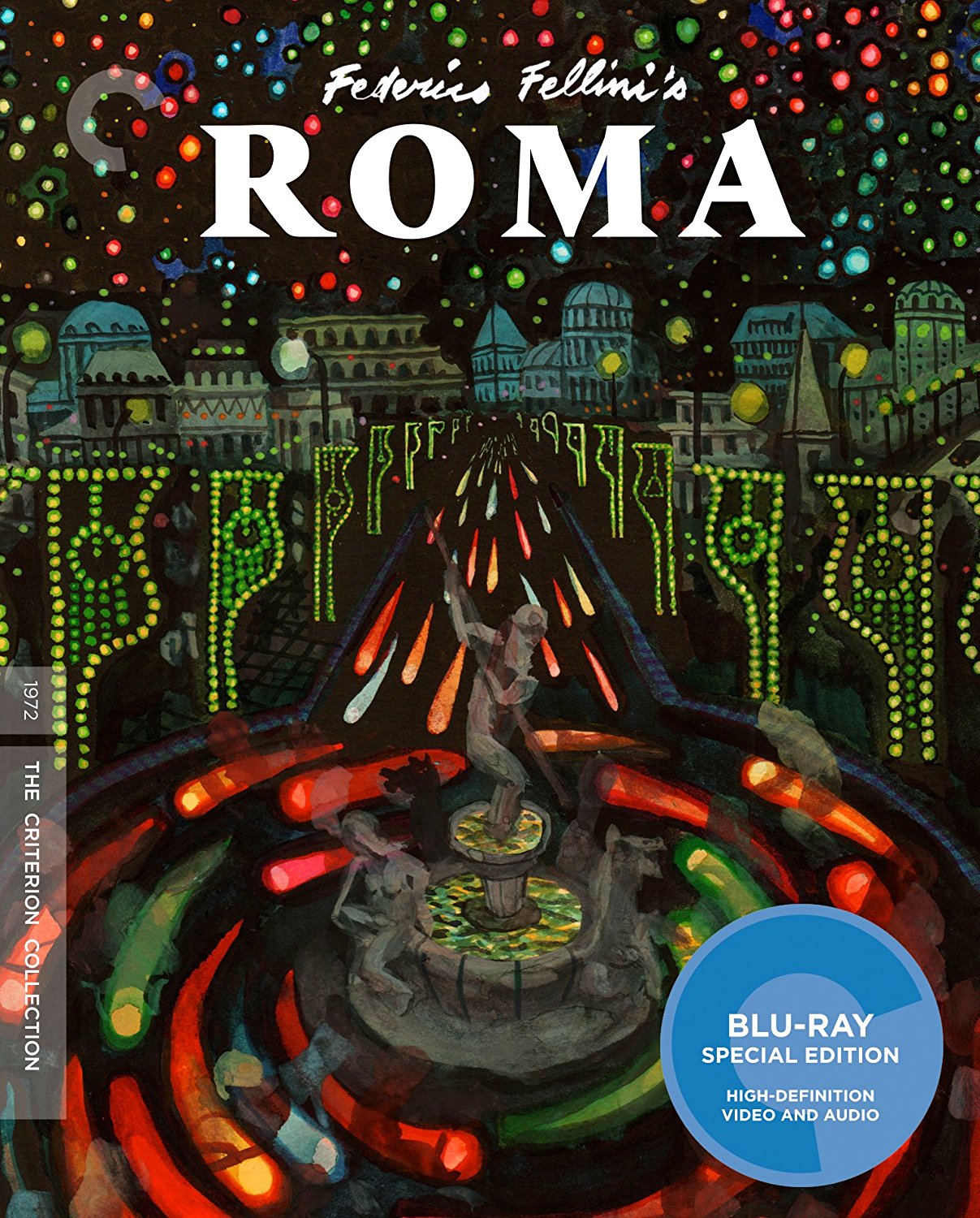

Also, it hasn’t looked much better than what Criterion has given us via their new Blu-ray. The 2K digital restoration is superlative. Done in 2010 at L’Immagine Ritrovata by Cineteca di Bologna, Cineteca Nazionale and Musco Nazionale del Cinema, this restoration comes from the film’s original 35mm negative, and looks absolutely superb. The nighttime sequences are particularly entrancing here, with their shades of blue making for some of Fellini’s most intriguing work in the film. The release itself is also quite good, with the cover art being a perfect entry point. It’s a gorgeous piece of artwork, and one that speaks to the busy, dream-like energy found in the title city. Inside the package is a interesting essay from scholar David Forgacs, that’s as exciting a read as the fold out pamphlet is somewhat annoying to handle. It’s a gorgeous mini poster, but trying to read on that large sheet is cumbersome.

There are a series of deleted scenes here which are interesting enough, as are the interviews with filmmaker Paolo Sorrentino and poet Valerio Magrelli. However, it’s the commentary here, led by Fellini scholar Frank Burke, that’s the real gem of this release. It’s a fine commentary, with enough contextual information with regards to both the production and the politics surrounding the film’s satirical voice that makes it a must for anyone interested in digging deeper into the picture. And it’s worth digging into as it’s one of the truly great and underrated gems of Fellini’s superlative career.