To most, American independent cinema began in the late 1980’s-early 1990’s. With the rise of names like Spike Lee, Richard Linklater, Kelly Reichardt and Quentin Tarantino, American Independent film has been the breeding ground for some of cinema’s greatest artists, and fostered some of cinema’s greatest artistic achievements. However, for anyone with even a surface level interest in independent film, knowledge of its deeper, decade-spanning history here in the US is quite clear.

Dating back to the very birth of cinema, independent artists of every race, creed, gender and sexual orientation have been creating films looking at specific experiences. However, many of these films, from the silent era to more modern times (Kelly Reichardt’s River Of Grass only just last year saw a real release outside of festival appearances) have gone relatively unseen.

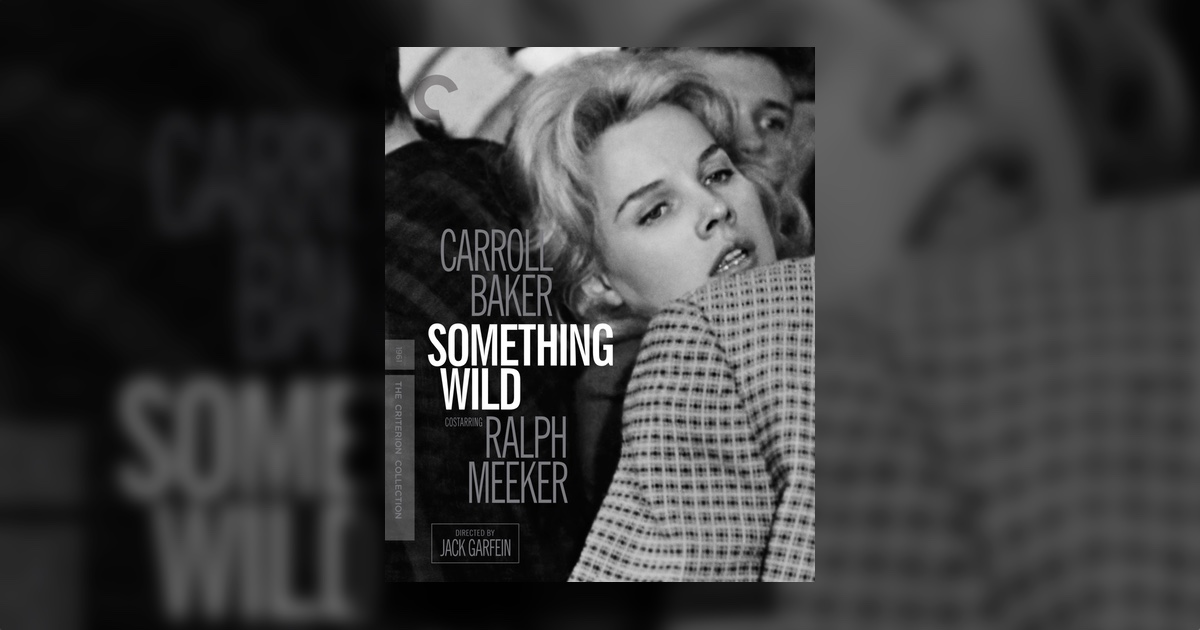

One of these films even comes from a prestigious pedigree. A product, of sorts, of the legendary Actor’s Studio in New York, Something Wild is the sophomore feature directing effort of Jack Garfein, a major player in the growth of that iconic collective. Gaining critical support recently, largely led by writer Kim Morgan and her programming of it on TCM and more specifically at a screening at the Telluride Film Festival, Wild spent many years as one of those storied “impossible to see” films that more often than not get lost to the annals of history. However, that’s not the case with this devastating piece of work, and it’s finally able to be seen and discussed as it more than deserves to be.

Starring Carroll Baker, Something Wild tells the story of Mary Ann (whose name the novel from which this film is based takes its title), a college student in bustling New York City. Opening with a Saul Bass title sequence that hints squarely at the tense energy held within the New York City of this period, the film then goes stone cold silent for an opening 20-plus minute sequence, relatively free of any dialogue that is one of mid-century cinema’s great sequences. Introducing us to Mary Ann as a vibrant, skipping college student, we watch as she makes her way through the city streets, only to suddenly get attacked by a stranger and subsequently raped.

From there we watch the effects of trauma weigh heavily on her, as she takes a bath trying to wash the memory out of her heart, ultimately leading her to nearly take her own life by leaping off a bridge. I say “nearly” because the film takes another turn when a second stranger, a mechanic played by the always alluring Ralph Meeker, arrives. Stopping her from jumping, Mike is no white knight. Subverting the clear expectation for the character to go from stranger to savior, Garfein’s film turns the interior of Mike’s apartment, where he takes Mary Ann for fear of her trying to kill herself again, into a cramped and claustrophobic cage. After various confrontations that show Mike as both aggressively compassionate and just down right aggressive, ultimately leading to Mary Ann taking out one of Mike’s eyes thus turning him into a cyclops in this epic poem of trauma and sexual violence. However, Garfein and writer Alex Karmel (author of the aforementioned source novel) subvert expectations one final time, leading Mary Ann to be set free, only to return to Mike’s arms in holy matrimony.

A startling achievement of tone and aesthetic experimentation, Garfein’s second and sadly final film (he’s currently an influential acting teacher) is a film truly unlike any other. Garfein tapped photographer Eugen Schufftan to shoot the film, and with that comes a very specific sense of style. Reminiscent of film noir in many ways, shadows play heavily into the film, the balance between light and dark giving Wild something of an otherworldly feel. Paired opposite occasionally New Wave-like exterior sequences (I’m thinking of a series of shots of Mary Ann walking the streets of New York City that feel ripped out of something like Elevator To The Gallows), Garfein’s direction is stylistic, expressionistic in its use of the frame and the angles from which he shoots. Particularly in the second half, when Mike arrives, the film seemingly turns on a dime, evolving from a naturalistic portrait of violence and the subsequent trauma, into something far more baroque, far more knotty. Is Mike’s keeping Mary Ann captive an act of violence itself? Is Mary Ann returning to Mike a bout of Stockholm Syndrome? Garnering great support in Europe, many have compared Garfein’s film to the works of Ingmar Bergman, and that’s about as perfect a comparison as one could make. The photographic comparisons are clear, as is the battle with guilt, shame and most clearly trauma. It’s a wonderfully moving motion picture, and Garfein’s direction is one major reason why.

But, jumping back to the opening series of shots, the portrayal of sexual violence and the human response to it is absolutely devastating and the film’s greatest achievement. Again, we are introduced to a bubbly, skipping young woman, who is savagely attacked by a name-less stranger in a brutally naturalistic sequence. Then, with a distinctly different energy, Mary Ann goes home, bathes, tears up her clothes and ultimately thinks of taking her own life. Told without much dialogue or even music, the film simply thrusts the viewer into this world, and with Baker’s performance at the core, there’s an almost Bressonian sense of realism to this series of scenes. Much will be written about this scene, and much should be written as its portrayal of violence and its effects on the human psyche are captivating and deeply insightful.

Opposite Baker is Meeker, best known as Mike Hammer in Kiss Me Deadly, who takes on a decidedly different example of masculinity. A knotty character himself, Meeker’s Mike is a complete subversion of the white knight lead. Slightly chubby looking with frazzled hair and a non-descript mechanic job, Mike is ostensibly a normal guy lacking empathy. Unsure why Mary Ann would want to leave, Mike more or less keeps her captive, making her lash out more and more, as one absolutely would given the experience she has just gone through. It’s a narratively dense film, and both performances are justly nuanced and engrossing.

Now on Criterion DVD and Blu-ray, this release marks its first real release on home video stateside, and is a superlative piece of work. The restoration is a gorgeous one, with the contrast coming through wonderfully, the blanks feeling inky and the whites almost blinding. Come the bridge sequence, the film almost embraces the grays of both the narrative and the city aesthetically, and the photography is as much a character in this production as New York itself. The aforementioned Kim Morgan leads a conversation with Garfein that’s a wonderful insight into the production of and response to this feature, and Garfein himself gives an interesting if not all that Wild-related acting Master Class. Carroll Baker gives an interview that’s insightful, and scholar Foster Hirsch looks at the film and its relation to Method Acting and the Actor’s Studio. All in all, this is a superlative home video release for a superlative piece of independent American cinema history.

[amazon_link asins=’B01M3Q7JQ8′ template=’ProductAd’ store=’criter-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’884aeaa3-df8e-11e6-964a-1196960b9dba’]