The use of “I” statements when attempting to review a piece of art is often times the sign of a weak or lazy critic. However, in the case of viewing the newly-released Kino Lorber Blu-ray of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (which comes hand in hand with a release of the iconic filmmaker’s equally revolutionary Le Gai Savior), it’s all but impossible not to give personal context.

One of Godard’s most esoteric and polarizing works, La Chinoise is a simply constructed story of a group of students, led by Jean-Pierre Leaud’s Guillaume, who form a Maoist revolutionary collective that ultimately sees extreme action as the only thing that can spark any actual change in the modern world. Leaud is opposite the brilliant Anne Wiazemsky who takes on the role of Veronique, effectively the co-leader of the small group, a group that draws inspiration from the students at the real life University at Nanterre, the school that would become the epicenter of student revolution in the late 1960s. Ultimately coming to the conclusion that only violence will bring about the change they want to see in the world, the group hatches a scheme that includes the assassination of a visiting Soviet author.

There’s a reason why La Chinoise sparks such heated debate amongst cinephiles, acolytes of Godard or not. Ostensibly ground zero for Godard’s evolution from simple cinematic experimenter into pop art satirist and provocateur, Chinoise is an entrancing bit of formalism. While the structure of the film and its subsequent narrative are simple in their execution, the philosophical ramblings are decidedly more obtuse than much of Godard’s previous work, and they’re also more nuanced.

I began this piece mentioning the use of “I” statements in reviews, and that’s simply because I myself have never truly seen a film evolve like this between viewings. I had previously encountered Chinoise during my freshman year of college, as I made my way through Godard’s oeuvre like any good college cineaste does. Upon first viewing, the brazen, Brechtian ideas and themes completely enraptured me. A burgeoning leftist myself at the time, the film’s central connection to leftist revolution and the idea of Maoist cultural revolution made it an instant favorite, if the aesthetics left me somewhat confounded.

Making your way through the Godard catalogue, this film truly stands out. A master of framing and composition, this is one of the director’s most simplistic and yet jaw dropping pieces of filmmaking. A film of dense themes and allusions, the film is also one of profoundly aggressive aesthetic choices, be it the surreal use of primary colors or the various moments of Brechtian playfulness. Godard is unwilling to ever let the viewer get their footing. He allows for lengthy filibusters from revolutionaries like Omar Diop, only to break the plane of reality itself by cutting to reverse angles showing everyone from a production assistant to photographer Raoul Coutard himself.

One of the film’s greatest moments is also one of its most breathlessly crafted, turning what is a simple two hander on a train into a crowning achievement in Godardian cinema. For a film told almost entirely in almost assaultive primary colors, we watch as Wiazemsky’s Veronique has a lengthy chat with a philosopher by the name of Francis Jeanson (who, it’s worth noting, was the actresses professor at the period of shooting), as she bares her soul about the violent plan she and her collective have formulated. The sequence is far more muted in its color palette, a moment of uncertainty that finds Veronique’s plan called squarely into question on idealogical grounds. It’s a moment of profound import to the proceedings, and despite its perceived simplicity, is a stunning scene that itself is a key to truly understanding this masterpiece.

Upon this rewatch, a full decade after I had previously combated this film, there’s one broad idea that becomes almost devastatingly clear. While young viewers may glom onto the dense ideas and manic pop-art stylings, there’s a profound sadness and conflict at the heart of the film. Weirdly moving in a way Godard’s cinema usually steers clear of, La Chinoise is one of the director’s most resonant works, a film of grays that is as potent today as it has ever been. For example, upon first viewing, one doesn’t take to the image of a student revolutionary painting on a wall in bright, primary colors as anything more than a playful bit of Godardian tomfoolery. But this film isn’t so much a film in support of revolution as it is a lament for the loss of the revolutions heart and soul. These are children who, yes are sincere in their progressive politics as only youth collectives can be, yet they’re ostensibly finger painting on the way to kill themselves. Tragedy hangs over each and every frame of this film, and only becomes more powerful and crystal clear as time paces and viewings stack up.

And without the top tier performances, across the board, the tragedy would be almost for naught. Leaud is at his very best here, bringing at once equal parts boyish charm and youthful assurance to a role that could be played as nothing more than a series of monologues. There’s a profound understanding of Godard’s intent within the Leaud performance, his character being more or less a stand in for the director himself. It’s a striking performance in a striking film. Yet the one who steals almost the entire film is Wiazemsky. A less talked about muse of Godard’s, Wiazemsky gives a gobsmacking performance in this film, one of earth shattering nuance and deep seeded tragedy. The above mentioned train sequence is a genuine key to understanding this film, and it is in her performance that the film finds its rare threads of genuine humanity. Juliet Berto co-stars, and gets to chew up some of the film’s most striking scenes, be it her playfully taking on the role of a Vietnamese woman surrounded by child-like paper airplanes or her readying for battle behind a wall of Mao’s Little Red Book.

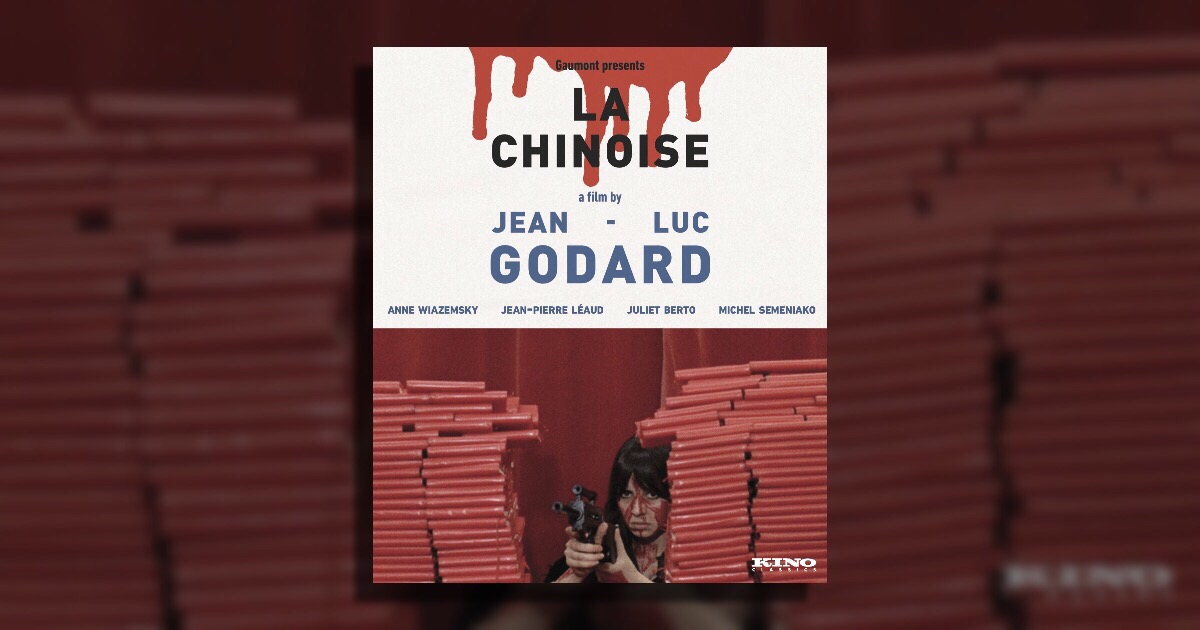

Coming prior to maybe his best film, Week End, La Chinoise is Godard in transition. Bucking his appreciation for Hollywood and genre, Godard jettisons anything really resembling coherent narrative for something entirely his own. Yes, the film holds within its DNA much of the Godardian playfulness that made films like A Woman Is A Woman the pop-art masterpiece it truly is, but there’s a profound regret and tragedy within this film that would only be heightened in the coming pictures. And thankfully, it’s finally available here stateside on DVD and Blu-ray. Gorgeously brought back to life by Kino Lorber, La Chinoise is one of Godard’s most beautiful films, and hasn’t looked better since opening weekend. The restoration here is top notch, particularly when highlighting the aggressive and assaultive primary colors that adorn the majority of this film. And unlike a great majority of Kino releases, this is a stacked Blu-ray. The film comes with a really engaging booklet which features essays from Richard Hell and Amy Taubin, and there is a jaw dropping cover that makes this a hard physical release to turn away from. Supplements include a superb commentary from historian James Quandt, and a series of interviews with those squarely connected to the film (like actor Michael Semeniako) and those who admire it (historian Antoine de Baecque). The interview with de Baecque is particularly interesting, as the critical view of the film is one of deep polarization. This isn’t one of Godard’s most talked about works, and yet with this release it’s rightly considered alongsides masterpieces like Breathless and Week End.

![La Chinoise [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41Im92jzE-L._SS520_.jpg)