It’s hard to consider the release of a piece of entertainment, specifically a DVD and Blu-ray box set, as a culturally significant moment, but then again there are few items quite like the newest release from the team at Kino Lorber.

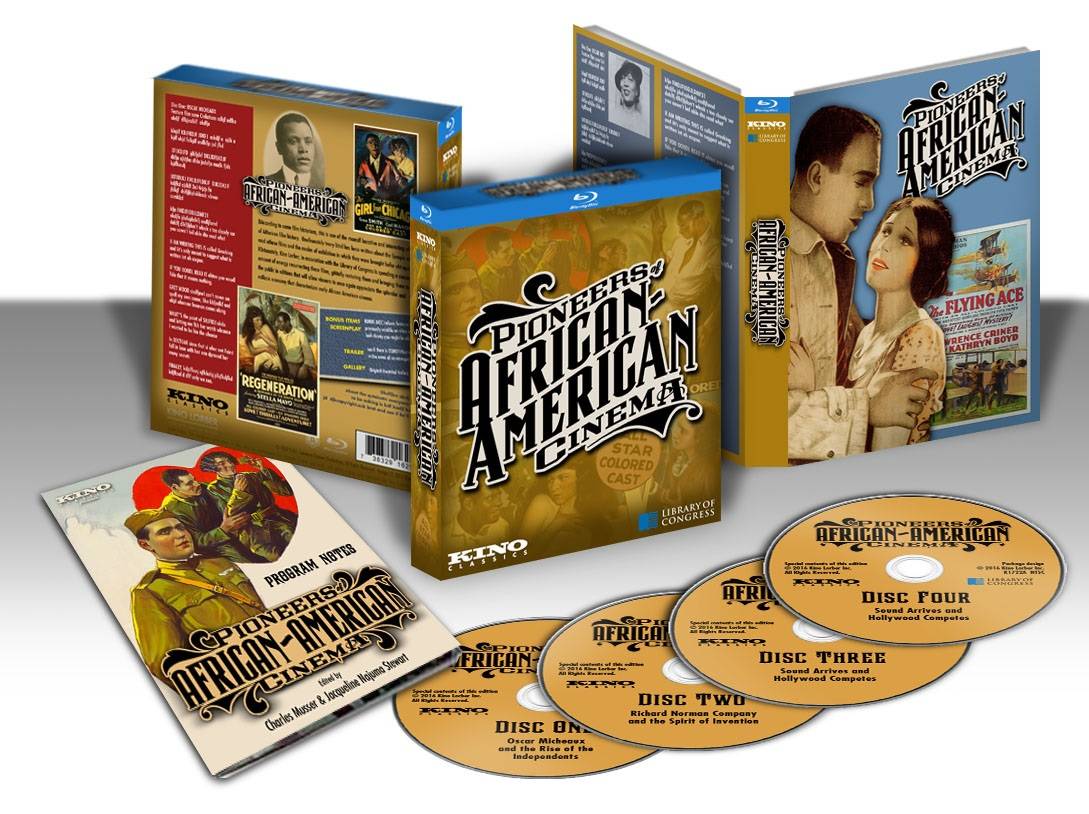

After a refreshingly successful Kickstarter campaign, Kino Lorber has finally released their groundbreaking collection, Pioneers Of African American Cinema, and to call it one of the year’s best home video releases is to truly understate the sociological import carried within this release.

Silent era and early-talkie cinema, as seen by many a film aficionado, is a deeply problematic world. Primarily helmed by white men, films more than occasionally featured everything from frustratingly cartoonish caricatures of African-American characters (furthering stereotypes like the “Mamie”) to white actors donning black face (of which there is also a great deal within this set as well) in what is seen today as a disturbing bit of racism. However, as this box set rightly points out, some of the most interesting and prolific filmmakers working during the earliest moments of film history are those African American directors who harnessed the medium to tell their singular stories.

One of the biggest highlights of this release, and the two auteurs whose vision most caught this writer’s eyes, are the husband and wife duo of James and Eloyce Gist. At first glance, the films look amateurish, with what is truly their masterpiece, Hellbound Train featuring a Satan character who is ostensibly a man in a Lycra body suit gallivanting around a train whose cars each represent a different level of hell, or more poignantly a different sin that will send you straight to hell. Be it listening to jazz or committing adultery, these sins are discussed and shown in what is one of the clearest representations of the type of “race” picture that was being produced around this period. With startling jump cuts that showed the filmmakers’ use of in camera editing due to budgetary constraints, Train is a breathtaking piece of lo-fi cinema, a roughly 50-minute meditation on the type of Christian culture that these two auteurs would directly play to. Impressionistic, these films are properly described as “spiritual surrealism,” with the narrative playing as a series of vignettes more than a truly coherent narrative.

And then there’s Verdict: Not Guilty. One of the numerous shorts held in this release, this is possibly the single most exciting discovery of this entire box set. Deeply haunting in its use of light and shadow, this tale of a woman who must try and prove her worth to God as she nears the end of her life is a briskly paced 7-minute short that shows the energy and vitality that would make this pair’s skim output so entrancing. Throughout this box, as we will discuss, the morality play is highlighted, and these films, which are rounded out by the recently discovered Heaven-Bound Travels, blend low-budget surrealist filmmaking that feels like the primordial ooze from which American independent cinema would be born out of with deep Christian themes, all forming some of the truly singular pictures of this time period.

That being said, the biggest name here, and the director whose work is both most influential and most worthy of re-evaluation and appreciation is that of Oscar Micheaux. The director of roughly 40 films, only about a third of them are still with us today, with none of them in their complete, original state. His greatest film, and the single most influential film amongst this entire box set, is the 1920 masterpiece Within Our Gates. The film tells the story of a woman attempting to start a new school, only to discover the racism within the very system she must go through to do so. It’s a beautifully made meditation on systemic racism that feels as rough around the edges aesthetically (Micheaux not only suffered from the same, above-mentioned budgetary constraints but also would himself, as a supplement here points out, be heard audibly directing the performances from behind the camera) as it does genuinely moving and deftly nuanced. The performances are even engaging, despite the fact that it’s clear Micheaux is editing his film in camera, with jump cuts occasionally startling the viewer.

Micheaux’s name is all over this release, with nine of the director’s films highlighted here. These include the unshakable The Symbol of the Unconquered: A Story of the KKK and the pair of underrated masterpieces, Veiled Aristocrats, and Birthright. The latter is a remake of an earlier Micheaux film, with both being lovingly restored and in the case of Veiled Aristocrats, this release even goes as far as to clarify the plot of the missing first two reels by describing details taken out of a censor board screenplay preserved by the Library of Congress. It is in this type of restoration, this type of tender cinematic love and care, that makes this a truly historic home video release.

The director’s earliest venture into talkies is also worthy of discussion. A short film entitled Darktown Revue, the film is an 18-minute long piece with a thin narrative, that is highlighted by a cavalcade of stage performances, ranging from choral numbers to a comedy vaudeville duo riffing on a haunted house. It’s not particularly well made and feels distinctly like an experiment testing what can be done with a new language for Micheaux, but the time capsule quality of this short is really entrancing. It comes off as a sociological curio, but its inclusion here highlights the type of collection Kino hoped to curate.

The other major director highlighted here is Spencer Williams. Best known as TV’s Andy, from the legendary show Amos n’ Andy, Williams is a director whose work, even more so than Micheaux, has gone largely unsung within the annals of film history. The Blood of Jesus is his most talked about, and arguably greatest, work, a style of moral melodrama that he’d go on to make a career out of. It’s a gorgeously composed picture and features some of this box set’s most interesting performances and directorial choices. Other films from Williams show the variety held within the filmmaker, with another melodrama like Dirty Gertie from Harlem USA playing opposite the entertaining The Bronze Buckaroo.

When taking a look at a set like this, much of the discussion must be placed around the restorations. Making a clear choice to both restore each film with great nuance while not shying away from including pieces of footage that are ostensibly unwatchable, the team behind this release allow each piece to show its age through grain and some wear and tear while including some short bits of footage that are beyond repair simply because it’s all that remains of a specific release. Something like the remaining scenes of Richard E. Norman’s Regeneration, all 11 minutes of it, are relatively impossible to truly comprehend and is largely unwatchable, but absolutely deserves to be included here as it is the remaining footage from an influential name in early African American cinema. Other films are much clearer and have been restored with a curator’s eye, finding that sweet spot where the footage is clearly restored but still carries the age that makes these types of films so thrilling to watch. There isn’t a moment while watching a film in this box set where one feels like the restorations are too clean, or too sterile, each film carrying with it an energy that comes inherent with a film that’s nearing its centennial anniversary.

There are also numerous supplements here that round out this release. Besides a look at the restoration process, there is an introduction to the set on Disc 1 and even a pair of trailers for the films Veiled Aristocrats and Birthright. However, the scores for two films are what will be the real talking point among the supplements here. DJ Spooky (aka Paul D. Miller, an Executive Producer on this set) scores two of these films, Body and Soul and Within Our Gates, with the latter playing out as one of the truly great modern silent film scores. It blends the classical silent film score composition style with the type of jazz-infused boom bap hip-hop production that makes DJ Spooky the influential name he is and is a work of high art all its own. These are just two scores among many new compositions found here, and highlight the type of respect given to each of these films and this release as a whole.

It’s impossible to hyperbolize about a release like this. Not only is it a beautifully curated journey through the early history of African American cinema, but it’s a curated box set that features some of the truly great silent and early talkie films of their time. From the spiritual surrealism of the Gists to the sociologically important works of Micheaux, this collection of films is a must own for cinephiles, and a worthwhile purchase for those with other sociological interests.