Seemingly for as long as the medium has been around, film has consistently been in conversation with and influenced by its elder sibling, theater. Be it the rather constant flood of screen adaptations of famous plays and musicals, or the actual aesthetic back and forth between the two mediums, film and theater are two vastly different outlets for artists to practice their craft within, while working vastly different muscles. However, when films attempt to blur the lines between these two worlds, some true beauty and greatness can arise. And therein lies Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge.

Set within the world of kabuki theater of the nineteenth century, Ichikawa’s film tells the story Yukinojo (Kazuo Hasegawa), a man raised since age seven in the arts not only of theater (he is known as an onnagata, or a male actor cast in female positions) but also deadly martial arts. Originally titled Yukinojo henge in Japan, that entrancing title translates to Yukinojo The Phantom, which is just as descriptive of the type of film Ichikawa crafted as its English An Actor’s Revenge titling. Yukinojo is a charismatic performer, whose androgyny allows him to slip into each role with precision while also allowing himself to become underestimated by those he wishes to attack. Orphaned as a youth, Yukinojo has grown vengeful, and Revenge finds the performer ready to strike in furious anger at the three powerful people who ultimately forced his mother and father to take their own lives. With cultural upheaval on the periphery, An Actor’s Revenge is not just an experiment in the blurring of stage and screen on a craft level, but is also a rousing and captivating meditation on vengeance, grief and art.

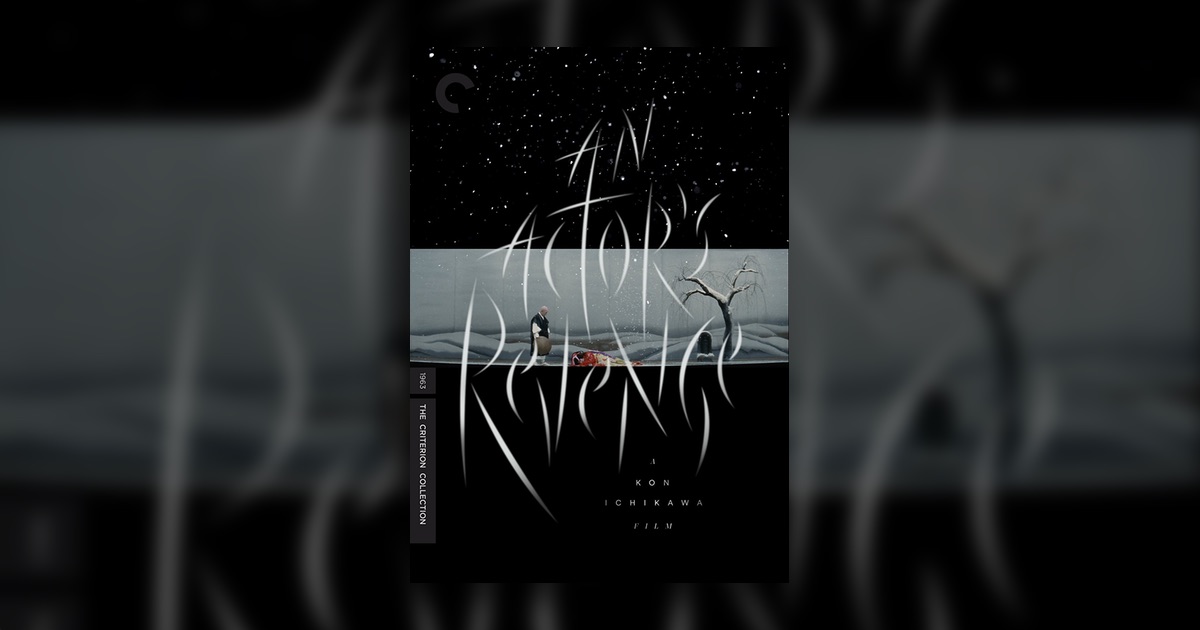

Better known for films like The Burmese Harp and the peerless Fires On The Plain (as well as a personal favorite Tokyo Olympiad, recently given a second life as part of Criterion’s Olympic box set), director Kon Ichikawa breaks entirely new ground with this film. Shot in anamorphic widescreen, the film does owe a great deal to theatrical framing and staging, but it also is one of Ichikawa’s most impressionistic and surreal works. From the lavishly produced stage sequences or the almost nightmarish “exterior” shots, Ichikawa’s film is one of of one jaw dropping sequence after another. The director flexes particularly in the sequences that see any number of our characters head out into the world, be it into a night that is shot against maybe the darkest black backgrounds in film history or forests that resemble something more akin to an acid-fueled watercolor painting than a naturalistic film thriller.

With wife Natto Wada aboard as co-writer, Ichikawa is at the height of his powers here. In full experimentation mode, not only is the director interested in conversing with both film and stage techniques but he’s also toying with genre here as well. Adding an extra layer to this tale of revenge by playing with gender throughout, Revenge is a haunting descent into the mind of a person consumed by the revenge they seek. Made manifest by Ichikawa’s expressionist film making and simply audacious flights of fancy. Something as simple as seeing the character of Yamitaro (also played by Hasegawa in his second of two performances here) climb up the side of a building with frightening ease carries with it an extra layer of otherworldliness thanks to both the frankness with which the act is happening as well as the lavish nature of the scenes staging. Everything here, aesthetically, feels of a world similar in structure to ours of this time but turned up to the proverbial 11. Ichikawa was a noted fan of filmmakers like Cocteau, and this influence is more than clear throughout this picture.

A star of literally hundreds of films (this marked the actors 300th picture), Hasegawa is also quite a revelation here. While he’s become one of Asian cinema’s great screen actors, this is a dual performance all its own. As Yamitaro, the smaller of his two performances, he’s admittedly playing something in a slightly lower register, but is quite great. However, as Yukinojo, Hasegawa returns to a role he previously took on for director Teinosuke Kinugasa, and turns in an all time great performance. Playing an actor playing a character, there’s always a duality to his performance, one that itself is both a put on and completely true. There’s something about the character that feels at once completely in keeping with the film’s heightened sense of surrealism and yet there’s an equal sense of truth to each of his emotions, be it performed by the character’s stage persona or actualized by the man behind the kabuki makeup. A character that’s completely unassuming to everyone he comes in contact with, this allows for the film to have a great sense of propulsion and tension, turning each action set piece into something as vital and captivating as any of the surrealist close ups that punctuate the picture. The film is as much a stage melodrama as it is a typical samurai thriller, and this mixture of tones and moods all with Ichikawa’s heightened atmosphere allows this otherworldly performance to really thrive.

There’s also a pair of key texts to truly getting under this film’s hood that come with Criterion’s new, and gorgeously restored, Blu-ray. On top of some new subtitle translations and a booklet including an essay from critic Michael Sragow and a piece by Ichikawa himself about his decision to work in anamorphic widescreen, the Blu-ray includes both an interview with scholar Tony Rayns as well as an interview with Ichikawa from 1999. The Rayns piece is a welcome journey into film scholarship, particularly looking at the placement of Revenge in the broader Ichikawa canon and also the role of Hasegawa in the film, with the archival interview with Ichikawa helping to get into the nuts and bolts of the film’s production, straight from the horse’s mouth. Both pieces are entrancing looks into the film, that are the types of deep dives that Criterion is best known for. And they’re welcome, because few films are at once this stylish and also this intellectually captivating. Simply put, this is an underrated masterpiece from an underrated master filmmaker.