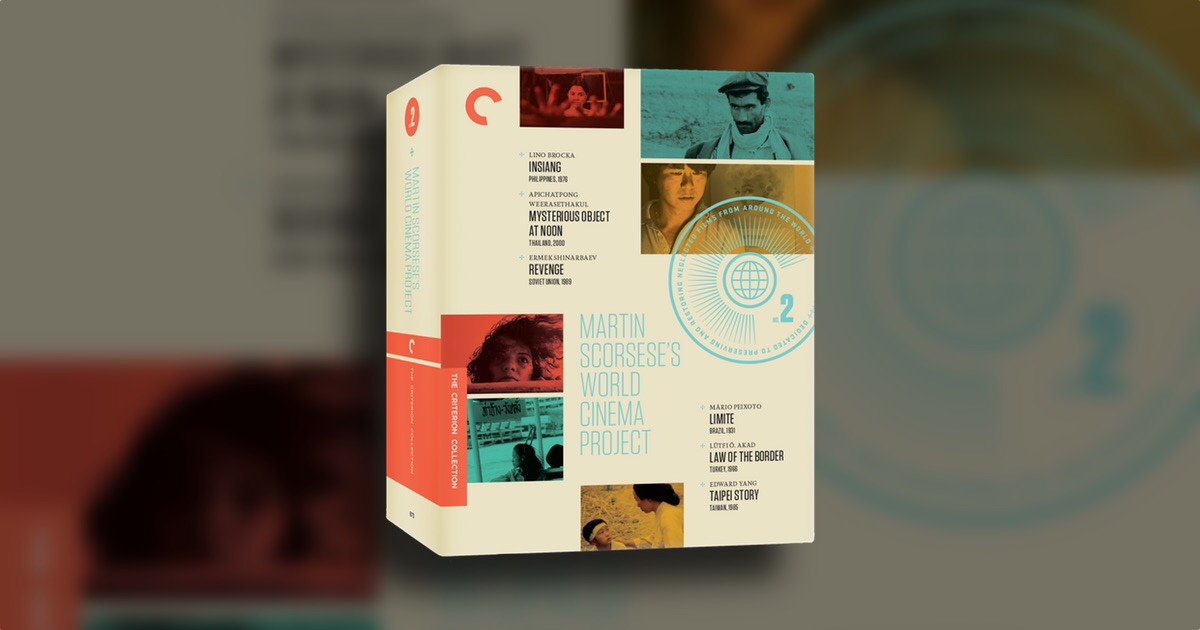

In those circles traveled by fans and collectors of anything home video, few things are more hallowed than The Criterion Collection’s first volume of their World Cinema Project DVD/Blu-ray series. One of the company’s most lauded and adored releases in recent memory, Volume 1 of Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project included six new restorations of six legendary films spanning the history of world cinema. From a foundational work in African cinema to a tale of sexual obsession that changed the history of Korean filmmaking, the first in this series has become one of the most important and exciting releases in recent Criterion Collection memory.

And finally, they’re back for a second round.

Again bringing to light six superlative films from across the world, “No. 2” as it’s billed on their website features a treasure trove of world cinema that in many ways rivals if not exceeds its predecessor.

First, the set introduces us to Insiang, the first film in the Collection from director Lino Brocka. The director behind the pending Criterion release Manila In The Claws of Light, Brocka is one of the great Filipino filmmakers, and it’s clear to see why. The first Filipino picture to play Cannes, Insiang tells the story of the eponymous young daughter and her mean-spirited mother. After she is raped by her mother’s younger lover, Insiang goes seeking revenge in what amounts to a thrilling and emotionally devastating meditation on life below the poverty line and the uncompromising nature of being a woman in this vicious world. At its heart a melodrama, Insiang features a brilliant lead performance from Hilda Koronel and is a strong and visually startling statement from Brocka. Unflinching about sexual violence, Brocka’s film is a moving and textured rape-revenge thriller, a film that is decidedly feminist and has deeply profound insight with regards to this type of horrifying trauma.

Opposite this film on the first Blu-ray (and it’s own DVD as this is the rare box set to get the Dual Format treatment) is the debut feature from the beloved Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul (or Joe, a name dating back to his days in college in Chicago and as he’ll be known for the rest of this review) A Mysterious Object at Noon. Joe’s first feature is a beautifully composed 16mm film shot in black and white, and couldn’t be further from the previously mentioned film it shares a disc with if it tried. Composed of mostly static, lingering shots, Object is a clear first step for Joe, as this gets to many of the director’s core themes. Blending fiction and documentary cinema, the film blurs the definition of reality as it tells the story of numerous unrelated people across Thailand tasked with the simple idea of telling the film’s director a story. Real or fake, the validity of the narrative is unimportant to the filmmaker, instead he uses documentary stylings to ruminate on a cross section of lives in Thailand and culminates with a performance of the newly spun fable done with non-professional actors. Very much rooted in the type of surrealism that would become a staple for the Uncle Boonmee auteur, this quiet and yet deeply moving hybrid film is as much a moving look at life in Thailand as it is a formalist breaking down of the boundary between fact and fiction.

On the opposite end of the narrative spectrum, there is the intensely plotted Revenge from director Ermek Shinarbaev. A foundational work in the Kazakh New Wave, this film finds Shinarbaev teaming with writer Anatoli Kim to tell a story that spans generations. Whereas Joe’s picture was interested in blurring the line between fact and fiction, Shinbarbaev’s picture is almost baroque in its ornate plotting, weaving a tale of revenge that begins in the 17th century and expands its reach in time while closing in its focus thematically. Broadly about the idea revenge and its passing down through generations, this narrative is broken up into various chapters that give the proceedings a truly fable-like feel. Beautifully composed, this is a deeply poetic picture, one that uses lighting in a painterly fashion, with each frame feeling like a piece of classical art. Its densely plotted, surely, but even more so it is a profoundly evocative lament about generational trauma that’s one of this box sets real discoveries.

Speaking of discoveries, its partner on the second Blu-ray takes the viewer not only into the world of silent cinema, but also that of Brazilian cinema. From 1931 comes Mario Peixoto’s Limite, one of the long rumored additions to The Criterion Collection. Ostensibly a collection of flashbacks had by three people stranded at sea, the film is set to legendary works of classical music, and some of the box set’s most startling images. It’s easy to see why, on the Criterion website, related films are Guy Maddin’s Brand Upon The Brain and Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet, as Peixoto’s picture is a surrealist piece of avant-garde filmmaking. Rooted heavily in expressionistic silent filmmaking with its use of close-ups and unsettling framing choices, this sole feature from novelist-turned-filmmaker Peixoto is an assured and poetic piece of visual art storytelling. While it may seem superficially interested in narrative, the real focus here is on the aesthetics, as Peixoto seems as interested in experimenting in cinematic language as he is in avoiding using actual verbalized language. Much like the work of Maddin, Limite is a deeply sensorial piece of work, proving once again that while it may have been young in terms of age, the early days of cinema brought to light some of the most visceral and affecting pieces of film art of all time.

Jumping 35 years forward, from 1966 comes Lutfi O. Akad’s Turkish masterpiece, Law Of The Border. Another film that owes a debt to documentary filmmaking of the time, Akad’s picture finds the director teaming with action star Yilmaz Guney, to tell the story of a man who takes on a seemingly impossible task to keep his son alive. As much a social realist picture thematically as it is a proto-typical Western narratively, Akad takes to genre storytelling to hint at deep and profound truths about life in his home nation. Rooted heavily in the style of neo-realism that swept cinema a little over a decade prior, Border is a well composed thriller of sorts that despite being seen in a rather rough state thanks to this “restored” print, is a rather affecting piece of filmmaking that’s quiet and yet packs a profound punch.

Finally there is arguably the greatest film of this collection, arguably this box set’s apex. Edward Yang returns to The Criterion Collection with Taipei Story, a brilliant masterpiece that sees the Taiwanese titan teaming with a contemporary. Starring master filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien, Taipei tells the story of a former baseball player turned textile salesman and his partner (Tsai Chin) as they navigate the ups and downs of their relationship. At once a story of love and loss and also a yarn looking at the evolution of the modernizing Taiwanese culture, this gloriously crafted melodrama is contemplative, moving and deeply assured. Quiet, yet startlingly stylized, Yang’s film is also co-written by Hou Hsiao-hsien, and features one of the set’s greatest restorations, highlighting the director’s use of space, particularly in comparison to the figures inhabiting it. Even in a crowded audience taking in a baseball game, there’s a sense of isolation and loneliness taking hold on its central figures, which is only heightened more as they inhabit spaces that are more and more feeling global influences. Stating that Los Angeles is “just like Taiwan” may not be the most subtle piece of dialogue one could imagine hearing, but there is something profound about that statement when taken in connection with the growing isolation felt by each half of this central couple as their grand hopes for their future are forever changed. Where the Turkish film that shares this final Blu-ray with Yang’s film is more interested in neo-realism, Taipei owes a great debt to the cinema of isolation that would take hold of Italy just a decade following its neo-realist phase. Simply put, this is one of Asian cinema’s greatest achievements, and it’s about time it finally arrives on home video here stateside.

Across the board, the restorations here are top tier. The set includes 2K, 3K or 4K digital restorations of the above mentioned pictures, and while some are in disrepair simply due to the spanning of time (Border is again particularly rough), there is a real love and care that went into each restoration, done with assistance from the WCP and Cineteca di Bologna. Now the interesting debate begins.

What makes a great home video release? Is it the quality of the restoration? How about the sheer fact of a rare picture finally being available widely? Or do you need something more? Because the supplemental material here is weirdly thin. Each film gets an introduction from Martin Scorsese which are fun, but far too brief. More interesting are the essays that are included in the gorgeous booklet that accompanies this set, particularly Dennis Lim’s look into Mysterious Object at Noon. Lim is a superb writer and one who is as deeply insightful as he is incredibly engaging to read. Each film gets an interview segment, with historian Pierre Rissient discussing Insiang, Weerasethakul talking Noon, Shinarbaev musing on the making of Revenge, Walter Salles talking Limite, producer Mevlut Akkaya chatting about making Border and the pair of Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edmond Wong talking about Taipei Story. Each interview is engrossing in its own right, but again doesn’t add a great deal to an otherwise incredible box set. It’s great to have these segments, but the box set itself doesn’t dig quite as deep as one would expect if each of these films were given a single release.

That being said, it’s all mincing words at this point. This is one of 2017’s great home video releases, and yet another deeply important release from The Criterion Collection.