When looking at a director’s canon upon its completion and in its entirety, the final piece of work is more often than not a key text in the broader understanding of the respective oeuvre. Be it something as relatively modern as Robert Altman’s masterpiece A Prairie Home Companion or a classic gem like the underrated Fritz Lang picture The Thousand Eyes Of Doctor Mabuse, these career-capping works may not be the director’s greatest achievement, but they see the director at a defining moment in their career.

However, few “final films” may be as singularly important in a director’s career as the one that would close out Robert Bresson’s legendary life, L’argent.

Now available on Criterion DVD and Blu-ray, L’argent tells the story of not so much a living character as it does an entity that runs roughshot over the lives of many. Similar in many ways to maybe Bresson’s most iconic work, Au Hasard Balthazar, L’argent is billed as a tale of “original sin” that follows a counterfeit bill birthed out of innocent yet damning prank, only to make its way into circulation and forever change the lives of everyone it comes into contact with.

Based ever so loosely on The Forged Coupon by writer Leo Tolstoy, Bresson’s “adaptation,” if you will, first introduces us to a young student in need of cash to not only go about his way for a month but an advance to pay off a friend. When his stern father denies him the advance, the student goes to a fellow classmate who informs him of a counterfeit bill he’s made. They pair then subsequently go to a camera store, where the manager later discovers the bill was forged. Decisions become even more damning when the manager decides to try his hand at going around authorities, simply handing off the forged bill to an entirely innocent gas purveyor, played brilliantly by Christian Patey. The closest thing to an actual lead this film has, Yvon’s life is then sent into a downward spiral as he goes to by dinner at a restaurant one evening, only to have himself put in cuffs after the restaurant sees the bill is a fake. However, with a job now lost, he’s sent into a life of crime that sees him become a getaway driver for a foiled bank robbery which sends him to jail for three years, seeing him lose his wife and discover that his daughter has died. A deftly crafted and deeply heartbreaking meditation on class, this spiritually shattering piece of filmmaking is inarguably one of the great achievements from one of film’s great poets.

Criterion billing this tale on the back of their beautiful new DVD and Blu-ray of this film as a story of original sin isn’t just flowery language attempting to sell a product. Across the director’s career, religion and specifically the Catholicism of which he was raised within has played as much a part in his overall artistic project as sound design or his use of close-up. Greed is at the very core of this film, and its effects are seen increasing exponentially throughout its briskly paced runtime of just under 90 minutes. Born out of nothing more than teenage playfulness, the 500 franc note at the center of the film goes from boyish one upmanship to all out capitalist greed in the hands of the camera store manager. We watch as, to save his own proverbial ass, he and his employees lie their way to safety, ultimately playing their upper crust class status as a trump card when caught in a war of words with police and our lowly gas man.

As much a Catholic man as he was an existentialist filmmaker, the core of this picture (released in 1983) could have been played as a film noir just thirty years prior. Corruption runs rampant throughout here, not in the way of dirty cops or femme fatales, but in a far more cosmic, metaphysical way. Souls are corrupted here. The world our characters inhabit is corrupted. Through a simple story of a floating bill, Bresson’s quiet filmmaking is able to get to the core of human nature and the ease with which we become corrupted in the hopes of self preservation. Yvon is a proto-typical noir hero, a lower class man simply doing his job only to find that forces above and beyond him have stacked the deck in ways far passed his control. Maybe more so than any of Bresson’s films, this is minimalist storytelling for maximalist effect.

L’argent is also an aesthetic achievement for the filmmaker as well. A master of sound and editing, both are on display in brilliant fashion here, be it his use of sounds scenes in advanced (there’s a sequence here where the soundtrack is playing sound that we won’t see materialize until two cuts later, and it is absolutely gobsmacking) or the editing of action set pieces. That’s right, even Robert Bresson dabbled in action filmmaking, albeit in a startlingly minimalist manner. We watch Bresson cut a car chase with only as many edits as he could count on one hand, and there’s particularly a sequence involving Yvon grabbing someone that’s told through close-up and a series of edits that’s one of the most shocking moments in the director’s career. Even the spilling of a liquid near the film’s conclusion is played with the utmost seriousness and weight, showing that few filmmakers got the power of editing and sound quite like Bresson.

Bresson was also no slouch behind the camera, rarely better seen than within this film. Told almost exclusively through static shots and even more static performances, Bresson utilized his frame in ways few directors seem interested. A master of the close-up, L’argent’s story is told most effectively in these sequences, as they give the film a deeply profound sense of claustrophobia. A sequence like that above-mentioned confrontation, these moments are given immense weight through the intimacy of the camera, as if some higher power is taking note of it in their ultimate ledger. Particularly near the film’s conclusion, where Yvon takes matters to their ultimate conclusion, the bluntness with which things happen is a testament both to Bresson’s deft hand with his frame and also the bewildering power of a static, disaffected camera.

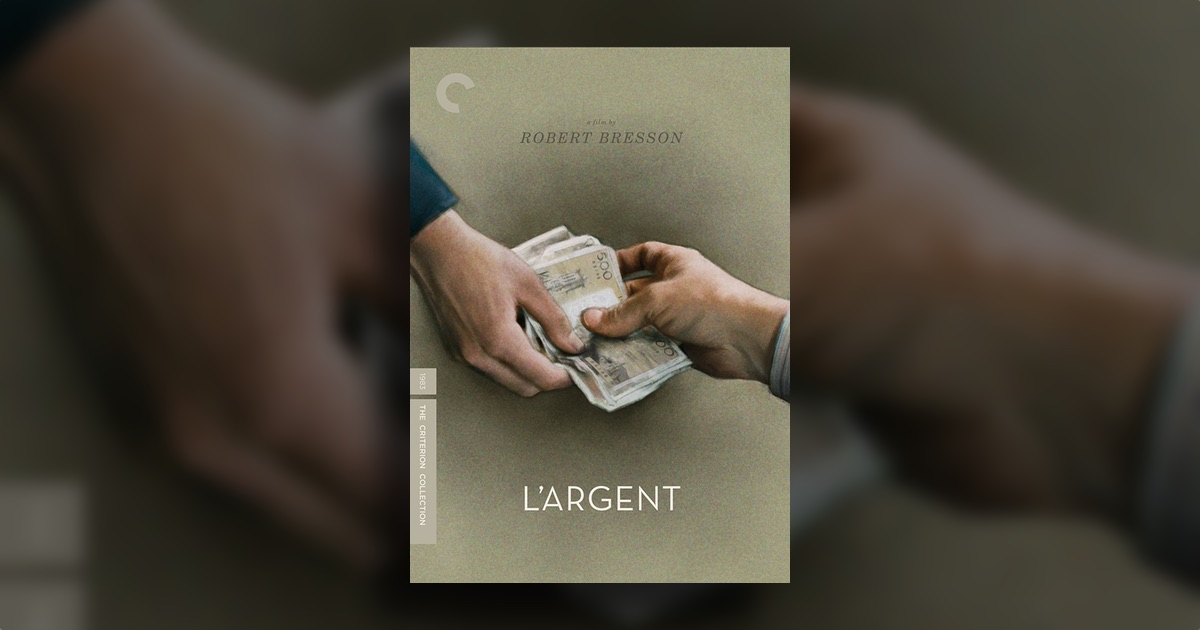

But why should I keep talking when the new, and beautiful, Criterion Collection Blu-ray has, itself, a rosetta stone text within its supplements. Besides a gorgeous transfer and captivating cover art, Criterion’s release has what tech and gaming people would describe as a “killer app.” You know, that one thing that makes you need to own a release. That’s James Quandt’s L’argent, A to Z. A fifty minute video essay looking at the film and its director through a series of ideas built around each letter of the alphabet, this supplement is a profoundly interesting document for those new to Bresson’s work or students of the master. Ostensibly the only real supplement here (a 1983 Cannes press conference is fine but unimportant), this essay is a masterful piece of film scholarship that is in and of itself one of the best supplements Criterion has produced at least in 2017 if not far longer. It turns this from simply a presentation of a masterpiece, to a must own deep dive into not only one of the great films of all time, but one of the great film makers.