Because Life of Riley ended up being his final film – he passed away a month after its premiere in Berlin last year – fans of film director Alain Resnais have been eager to attach a great level of importance to what would already be, for us, a very important film; after all, it’s the new Resnais. I’ll admit myself to instantly reading it along auteurist lines, how it develops and plays with Resnais’ continued fascination with death, and his increasing acceptance of growing old. So much of Resnais’ late cinema is spent trying to recapture youth, from perspectives formal (Wild Grass has twice the energy of the films produced by directors a quarter of his age) or quite literal (You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet observes a group of actors playing parts they had played decades prior). Yet by the end of Life of Riley, itself about a group of older actors, the principals have come around to finding something beautiful in the time they’ve invested in one another, and relish the beauty of growing old together.

Adapted from a play by English playwright Alan Ayckbourn, who has twice before provided the inspiration for Resnais films, Life of Riley is a delightful trifle of a thing. In it, the forever-offscreen (but apparently quite vivacious) George Riley is given months to live, and his friends are rushing about to make these final days as fulfilling as possible. We never see them attempt this directly, only hearing their versions of their success in so doing. It does not seem to be going well. George is withdrawing from his male friends, and nearly exploiting the women, all of whom are his former lovers, who have now settled into more permanent relationships. Yet all long to be part of the final phase of his life. It amounts to a lot of silly quibbles and misunderstandings that reveal larger unspoken truths about their relationships. It is, then, the quintessential British farce.

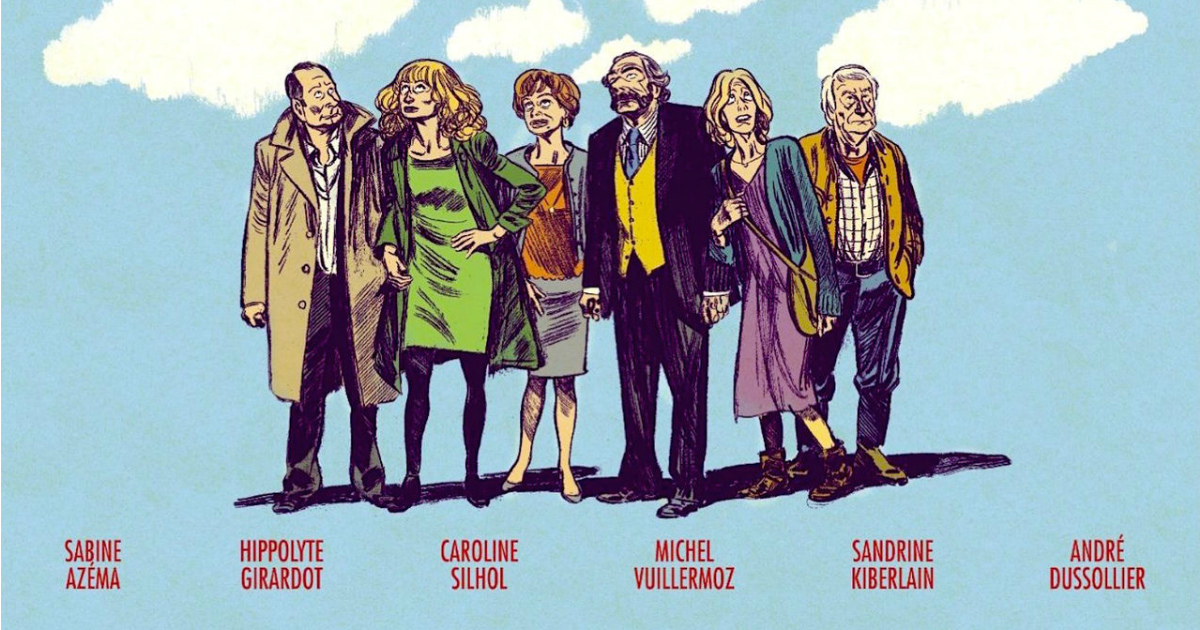

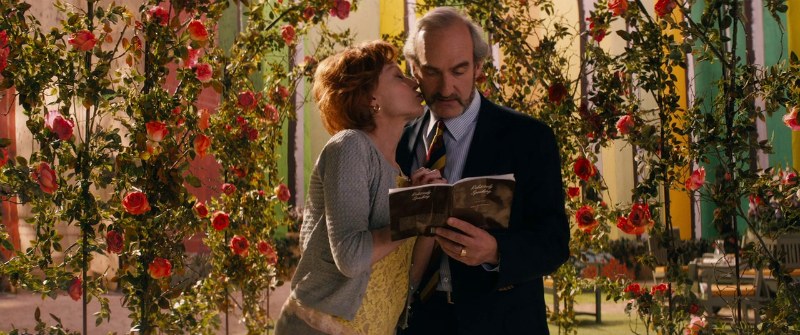

Whereas Resnais took Ayckbourn’s particular brand of silliness to near-cosmic heights in the interwoven, wandering, hilariously absurd Smoking/No Smoking, and found something sort of grandly beautiful about walking in on someone watching porn in Private Fears in Public Places, Life of Riley seems a fairly straight adaptation. The action is confined to the homes (mostly exteriors) of its main characters, but the entire film was shot on a soundstage. The sets themselves are almost cartoonish in their design; it’s worth remembering that in addition to his love for theatre, Resnais adored comics. The sets find inspiration in both mediums, and when he cuts to close-up, a cross-hatch pattern appears behind the actors, much how a comic strip’s background can quickly turn minimalist. The camera cuts as little as possible, and its movement is confined to what might be charitably called 2.5-dimension spaces. That is, there is a sort of “proscenium” it never crosses, but it might gaze back and forth along the stage it observes. One has to largely contend oneself with the framing alone, and the masterful performances going on within it.

But what framing. And what performances. This stripped-down approach to cinema goes back to its inception, when similarly obviously-studio-set films by Méliès, Griffith, Chaplin, and many more used seemingly simple master shots to convey the breadth of the space, the actors’ movements within it, and account for all their reactions within the frame. Resnais employs a bit more in the way of camera movement – slight tracks, a couple pans – but is counting on his actors to carry it. Sabine Azéma, Resnais’s creative partner for thirty years (and wife for sixteen), carries the show, as she tends to, bopping along with the curiosity of an adolescent damned with the life experience of an older woman. Of her cohorts, Michel Vuillermoz and Caroline Sihol (he a frequent Resnais player, she having not worked with him since 1989) fit in best within this world, playing a believably-seasoned married couple whose earnest desire for affection is cut with occasional games and playfulness. André Dussollier, who commanded Resnais’s Wild Grass five years ago, seems a bit out to sea here, but he is not given a great deal to work with.

This is Resnais’s first film shot digitally – though his last two were not shy with visual effects – and while I miss the soft haze that surrounded his past images, his aesthetic here does work well alongside his production method. It certainly makes for a relatively straightforward transfer to Blu-ray, and Kino has done an excellent job representing the film’s color palette. As one would expect, the image is sharp, damage-free, and I didn’t notice anything in the way of compression.

On the special features side, we get a nice little supplement gathering snippets of interviews with the cast, who lavish praise on Resnais, and talk about how the film fits into his larger filmography. Better, though, is the booklet, with a forward by Resnais and an essay by film critic Glenn Kenny, both of which serve to illuminate the film mightily.

This is actually the first Resnais film that has been put on Blu-ray upon its initial home video release, and I am very glad Kino took that extra step in releasing it. While his films rarely had anything in the way of a wide theatrical release (I remember seeing Wild Grass with about two other people in the audience during the one week it played in Portland back in 2010; I could only see You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet at a film festival), Life of Riley was especially ignored by exhibitors (it didn’t play at all here in Los Angeles), making it all the more important that this receive the best home video presentation possible. It has, and so I thank them.