The Nikkatsu logo, especially in the late 1950s and early 1960s, was a bit of a promise – 80-100 minutes of wild guys, sexy ladies, mob showdowns, a handful of visually-striking locations (get ready for nothing but bars, nightclubs, and docks), and a good deal of brooding over morality before the inevitable eruption of violence. These were as programatic as they come, yet within those strictures, the filmmakers under contract to the studio found enough room to practice some pretty wild stuff, or at least have some fun in so doing. Though the true classics from the studio (especially those by Shohei Imamura and Seijun Suzuki) were definitely outliers, to the point that the directors behind them were punished or fired for making them, that baseline promise captured the imaginations of young moviegoers at the time and have remained steadfast pleasures for today’s cinephiles.

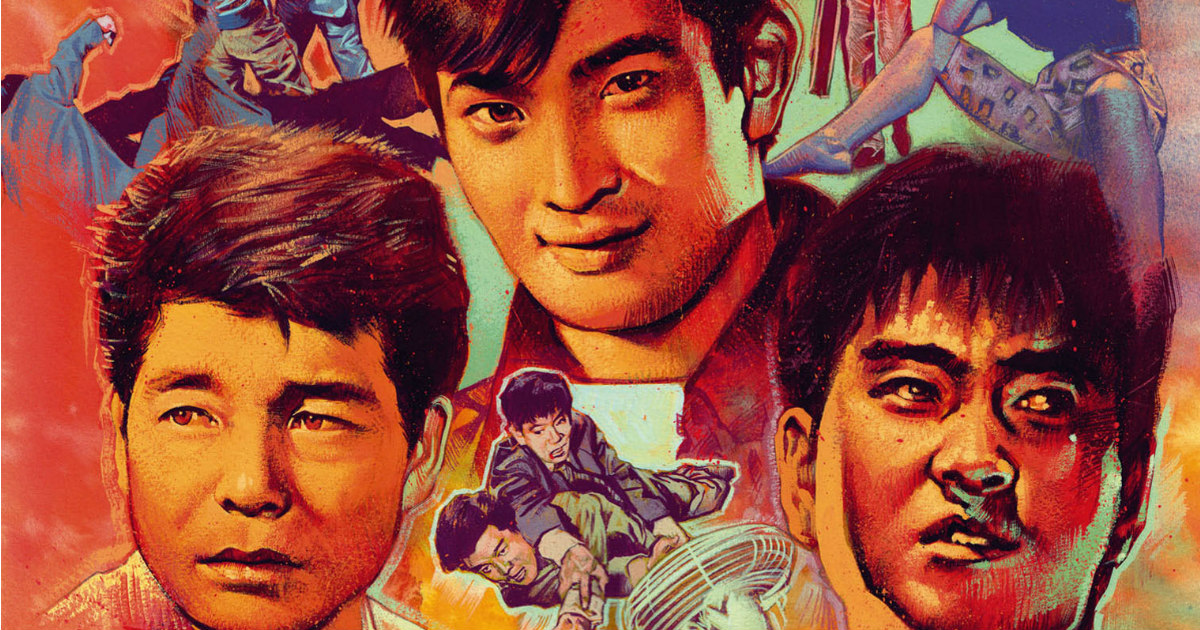

For those whose curiosity was piqued by films like Branded to Kill or The Insect Woman, Criterion’s Hulu channel provided a great outlet, as did their 5-film Eclipse set, Nikkatsu Noir. Now, Arrow Video has made a similar plunge into the sampler package with their Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol. 1, which brings three films by Suzuki, Toshio Masuda, and Buichi Saito to high definition. Each presents a different angle to Nikkatsu, how its requirements were stretched and recalculated, and each offers a fair share of the sort of base pleasures their name promised.

Suzuki’s A Voice Without a Shadow starts as the most unique Nikkatsu film I’ve ever seen, if only because it actually features a woman in the leading role. Yoko Minamida stars as Asako, a housewife haunted by the voice of a murderer whom she heard over the phone three years prior, when she worked as a telephone operator. Now, she is reintroduced to that voice when her husband invites his boss over for dinner and games, a meeting perhaps not as coincidental as it first seemed. Suzuki mines a lot of material from Asako’s paranoia and growing terror, which, alongside an opening flashback detailing her original ordeal, made this compelling right from the start, but unfortunately the film quickly detours into a standard-issue detective story, removing us from Asako’s point of view almost entirely. That plot works quite well on its own, but given what the film set itself up to be, it feels like Suzuki (and screenwriters Ryuta Akimoto and Kan Saji, adapting a novel by Seicho Matsumoto) just couldn’t figure out what else to do with her, and pasted on the remnants of an otherwise-abandoned idea to compensate.

Things get a bit more familiar in Masuda’s Red Pier, about – just you wait for it – a talented killer on the run after witnessing a murder meant to look like an accident. Oh, and he romances the dead man’s sister, as she is the most narratively-convenient way to introduce a woman into the story. While the film has a number of very cool scenes – two men wait by a pool to shoot each other until some fire crackers go off, a later showdown in a hotel room full of canted angles – and ends on an unexpectedly poignant and mature note, it’s a bit of a slog to get there. The protagonist, like many Nikkatsu leading men, is obsessed with how cool he is, but star Yujiro Ishihara takes too long twisting that around on itself, and doesn’t offer a lot to compel the viewer between those two points. As much as modern cinematic taste isn’t geared towards performers who “play themselves” onscreen, one of the most difficult things to do in a movie is to simply relax and remain calm. It’s no major strike on Ishihara that he’s not particularly adept at it, but it does make him the wrong focal point for this type of film.

One need look no further for clarification on the importance of chill than Saito’s The Rambling Guitarist, about a street musician who finds employment as a mob enforcer after being first promised the job will allow him to kick back and drink all day. That it was the mob boss’ pretty daughter (Ruriko Asaoka) who swayed him is, I’m sure, no small factor. The man has his priorities in the right place. Star Akira Kobayashi possesses complete ease onscreen, making his early, more relaxed scenes – filled with guitar strumming and soft singing – far more compelling than the more dramatic work he’s asked to do as he gets deeper and deeper into the mob. Still, unlike the prior two films in this set, The Rambling Guitarist carries its narrative transitions extremely well. When it makes its sharpest turn in genre, it does so with a scorching flashback and added punctuation, keying the viewer into what it’s up to. The general set-up – a wandering guitar-playing gunman gets drawn into a violent world – draws immediate comparisons to Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar, and while the latter is probably still the superior work, Saito’s entry certainly deserves mention alongside it for getting to a similar conflict between the ideals of pacifism with the needs, both emotional and practical, for violence. Lead by a truly compelling, yet still very cool, leading man and a woman whose sexuality goes hand in hand with her confidence, this was the winningest film of the bunch, and well worth the price of the set on its own.

Smashing three widescreen films, even if they are fairly short (The Rambling Guitarist is a lean 79 minutes; Red Pier gets up to 99), will create its own concerns for compression, and indeed, these are largely nothing to write home about. Rambling Guitarist, the only color film of the three, looks best, bold and bright and crisp and well-textured. The other two suffer a bit in the area of detail and density, though none of the three are particularly strong on depth. The black and white films also don’t have the strongest, or most consistent, contrast, with black levels often varying in tone. All still sport a fair deal of damage, though nothing that detracted from the experience of watching. As is apparently common for transfers of old Japanese movies, the splice marks are visible for every single cut, which is a bit annoying, particularly during long dissolves between shots (when the marks are visible on both the fade out and fade in). All in all, this is a discount package – three films for a list price of £24.99 (or $49.95 for the U.S. edition) – so sacrifices must be made. (screencaps via DVD Beaver)

Sacrifices are also made on the supplements – look for solid video discussions with Jasper Sharp on Hideaki Nitani (one of the stars of Voice Without a Shadow) and Ishihara, along with a booklet with essays on all three films, plus director profiles. Not the most robust, but much appreciated, especially for the less-heralded players in these films.

All in all, this is a nice introductory package for those looking beyond the outliers of Nikkatsu’s catalogue. Only The Rambling Guitarist stood out as a truly excellent entry, but it is really just that good, and well worth seeing. The other two struck me more as curiosities, though Voice Without a Shadow has a very compelling first half that offers something well beyond what I thought Nikkatsu would be interested in during this period. The transfers are a little hit or miss, but more than get the job done, and even excel in the case of The Rambling Guitarist.