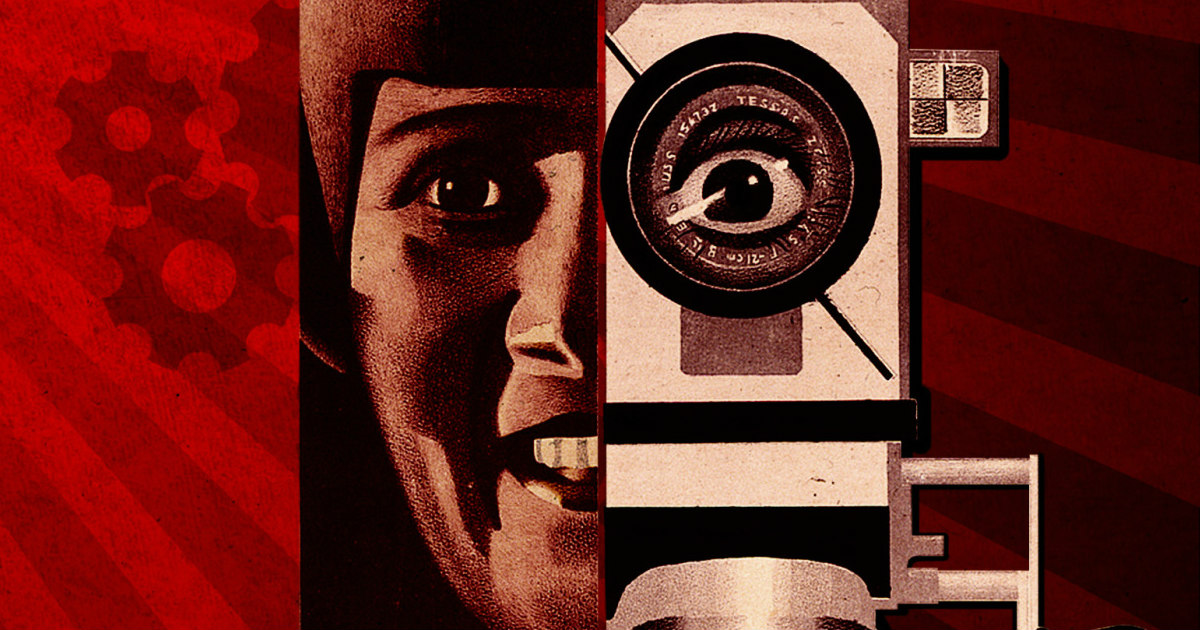

These were only meant to be seen once. These explosive, unwieldy, nearly unprecedented and almost peerless essay films, densely packed with images so resonant they have been studied for nearly one hundred years, were only meant to be seen once. This observation comes from Adrian Martin on the excellent commentary track accompanying Man with a Movie Camera (1929), easily Dziga Vertov’s most important film. The other four films on the set were produced contemporaneously – Kino-Eye in 1924, Kino-Pravda #21 in 1925, Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass in 1931, and Three Songs About Lenin in 1934. The latter two are sound films. The silent films – Movie Camera, Kino-Eye, and Kino-Pravda #21 feature musical accompaniment, none more accomplished than Alloy Orchestra’s landmark work.

For viewers in my generation, and I would imagine for a great many older than I, Alloy Orchestra’s score for Man with a Movie Camera is as important a component to the film as anything else. Following Vertov’s own musical instructions, they crafted a rousing composition with a clear theme with plenty of room to interact with the image, utilizing something like sound effects with their instruments (a “trick” we often see with composed – as opposed to accompanied – silent film scores). I’ve seen Man with a Movie Camera once with a different score, and it simply wasn’t the film. The feeling was that of someone’s voice when they have a cold; recognizable, but lacking distinction and clarity. Alloy’s work has proven, at least for me, essential to fulfilling Vertov’s expectation that Man with a Movie Camera would only be seen once – once is enough to make it stick.

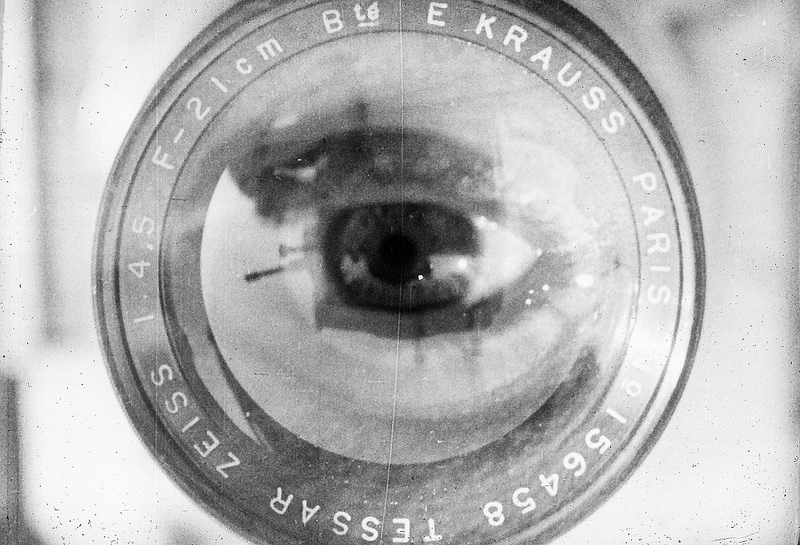

Which is not to say Vertov or his crew had no part of it. If I resist explanation of the film, it is because I cannot explain it. Man with a Movie Camera simply is. It’s a portrait of Soviet urban life in its time, but it’s so much more than that. It’s the yearning to express and the joy is expression. It’s wrestling with the physical means of production (factorial, governmental, societal, and cinematic) and fulfilling all the dreams one has in attempting to do so. It represents the total aesthetic freedom the of the silent era, complete abandon of plot or even narrative to the purpose of emotion, while not for a moment rendering itself into nonsense. It lacks all reason, yet makes complete sense. These contradictions are central to its lasting impression. Full as it is of indelible images (many, like the man with a camera standing atop another camera, becoming full-on iconic), it is the sensation of the images that lasts longer than any specific one.

If the other four films simply cannot reach the same heights, all the better. The first two are exercises on an artist’s journey to greatness. The foundations are clear, the curiosity is there, but not the complete inspiration and confidence in one’s abilities. The latter two, being sound films, are somewhat encumbered by the necessities of production. They open up more opportunities to play, but they close as many doors to the purity that came before. Not that they aren’t of interest, let alone good. Of course they’re good. In these films, Vertov finds more specific concerns that are merely suggested in Movie Camera, especially surrounding the physical toll of a society that so values labor. It is one thing to speak highly of the worker to rouse the populace; quite another to see what that worker goes through in a factory in those days. Every movement they make must be precisely timed, lest another movement – man, machine, or element – permanently disfigure or even kill them. And even when they do their job correctly, the palpable exhaustion is overwhelming.

So, too, is the effect of watching these films in close proximity, but such are the advantages of owning a handsome edition like that which Masters of Cinema has recently released. The restorations were overseen by Lobster Films, in coordination with multiple international archives and facilities, and the results are absolutely stunning. Man with a Movie Camera, in particular, looks so exceptionally good. Traces of damage remain, but the depth and texture are incredibly rich. This is as close a representation to a pristine film print of an archival film I’ve ever seen on digital. The other films, jammed onto a disc all their own, suffer a bit more for not being as elaborately restored, but they’re not overly compressed and just look like somewhat more worn film prints. The sound tracks on Enthusiasm and Three Songs are quite faded, and absent the subtitle tracks I’m not entirely sure I would be able to make out the dialogue. The rich, booming tones of the scores for the silent films go such a long way in matching the Vertov’s aggressive videos that faded soundtracks just seem so limp when paired with them. But what can you do; the films are the films.

The standout supplement is definitely Martin’s new commentary track. As with his previous contributions to MoC titles (The Tarnished Angels, Seconds, Fixed Bayonets), Martin brings a wealth of research and analytical insight, here packing a tremendous amount of observation into a comparatively short film without feeling rushed or hurried. He gets into a lot of the issues Western scholars have run into when approaching Soviet films, but is careful to try to determine what Vertov was after in the context of when he made it. Aside from that, there is a 46-minute interview with scholar Ian Christie and a video essay by scholar David Cairns, plus an incredible 100-page book stacked with essays, articles, and manifestos, many from the time in which the films were made. I am always impressed with the literature Masters of Cinema assembles for their releases, but this may be their finest, most comprehensive work since their Late Mizoguchi set.

Befitting one of the greatest films ever made, Masters of Cinema has gone above and beyond to celebrate the incredible new restoration they have on hand. Though also available in the U.S. through Flicker Alley (a company I love), I would give the edge to MoC for region-free viewers – it has one film the Flicker Alley set does not, and loads more supplements. This is one of the most exciting home video releases I’ve seen all year.