Leave it to Lubitsch to make a raunchy costume drama. After all, what’s the point of ruling a country if you can’t have a little fun with it, and if you’re inclined to have fun, why not gain a little power while you’re at it? It may be based in history, and a rather important entry therein (the years preceding the French Revolution were no joke), but that hardly means the people, in their time, did not live to the fullest.

Lubitsch seemed to find most everyone silly, especially if they were wealthy. The Oyster Princess, his most outrageous feature, concerns the marrying arrangements of the 1% of the 1%, while the moneyed doofuses who populate so many of his pre-code features seem too preoccupied with their own libidos to actually be much good to anyone. Indeed, in 1919’s Madame Dubarry, King Louis XV (Emil Jannings, beautifully playing The History of the World‘s refrain, “It’s good to be the king!”) could hardly be less concerned with the affairs of state while his titular lover (Pola Negri) teases him in ever more provocative manners.

But then, Dubarry* can afford to. She has no responsibilities, no obligations, no real power. Yet her influence is considerable, all of it self-serving. There certainly comes a point at which her indulgences stretch too far, yet for much of the picture, Lubitsch can’t help but admire her cunning. See, while Lubitsch thought the upper crust ridiculous and simply didn’t know what to make of the impoverished, he seemed to genuinely admire those who rose from meager stations toward a sort of refinement. One might look at the leads in Trouble in Paradise, The Smiling Lieutenant, Design for Living, To Be or Not to Be, or even his short segment in the omnibus film If I Had a Million. For Lubitsch, the most interesting people were those who could transcend, or who seek to transcend, their determined station, achieving a degree of class and sophistication without succumbing to too many of the manners that stifle the upper class.

This is best shown when Jeanne Bécu, before she becomes Madame Dubarry, is first introduced to the king – after being thoroughly schooled on the formal requirements for such an interaction, she introduces herself properly, then quickly kisses him on the cheek and smiles playfully. She broke protocol, but from that moment on, the king is hers, and the scene culminates in perhaps the most overtly sexual image of Lubitsch’s entire career, as her new beau slides a rolled document down her blouse, between her breasts, an indulgence by which she seems equally delighted. If Lubitsch’s rising proletariat can fleece the upper class, be it through theft, cleverness, or simple employment, all the better, but there’s no reason such an endeavor need be purely mercenary. In The Smiling Lieutenant and The Merry Widow, Maurice Chevalier is our hero precisely because he has achieved a rank that allows him to do very little professionally, while leveraging it quite significantly to do a great deal personally.

Similarly, Lubitsch marvels at Jeanne’s ascension from a dressmaker’s assistant to King’s official mistress, regardless of the many torrid arrangements that made it possible – including marriage to the wastrel brother of count Jean Dubarry, who in turn was her lover for a time, as a means of securing a title that would allow her to reach her eventual position. Yes, in those days, even adultery was formalized, at least in certain circles. That Jeanne could leave behind a slew of lovers as she progressed is of little consequence to her, but her drive is not portrayed as some power-mad trip of selfishness in the mode of, say, Baby Face. For Lubitsch’s Jeanne, sex is simply more fun when you get the dresses, jewels, and palaces along with it, and there really are few actresses better capable of playing this than Negri, who beautifully encapsulates Lubitsch’s frequent quest to have his audience laughing and turned on at the same time. Her sexuality is her key tool, but one she only leverages with a playfulness that keeps her in control. Each successive lover is her playmate, but she decides when playtime is over.

That she seems totally devoid of the sort of class consciousness that might have prevented the soon-to-follow French Revolution is fascinating; perhaps she simply is selfish, or perhaps she believes the monarchy to be so permanently instilled in France that there’s little harm in claiming a piece of the pie. Whatever the case, her thoughtlessness would cost her dearly, a fate Lubitsch shows in startlingly graphic detail. It drives the point home, but Lubitsch’s interests are too divorced from the plight of the lower classes to make this section all that compelling. His portrait of them is certainly sympathetic – if he has any fault, it’s in too greatly revering their suffering – but it ultimately turns on the very simplistic duality that any group with too much power will end up subjugating another. And besides, it ends up pushing Negri offscreen right as everything is climaxing, which is rarely a good move in such a star-driven production.

Still, it’s a refreshingly dynamic film for its type, wildly out of step with the often gloomy and self-serious historical dramas that clogged the screen then and now. Lubitsch recognized that people of tremendous importance are still full of humor and livelihood, a kind of approach that would rarely be taken in the decades to come (though reclaimed here and there by the likes of Sofia Coppola, for instance, with Marie Antoinette, which overlaps a good deal with this film chronologically, tonally, and thematically, and would make a wonderful companion).

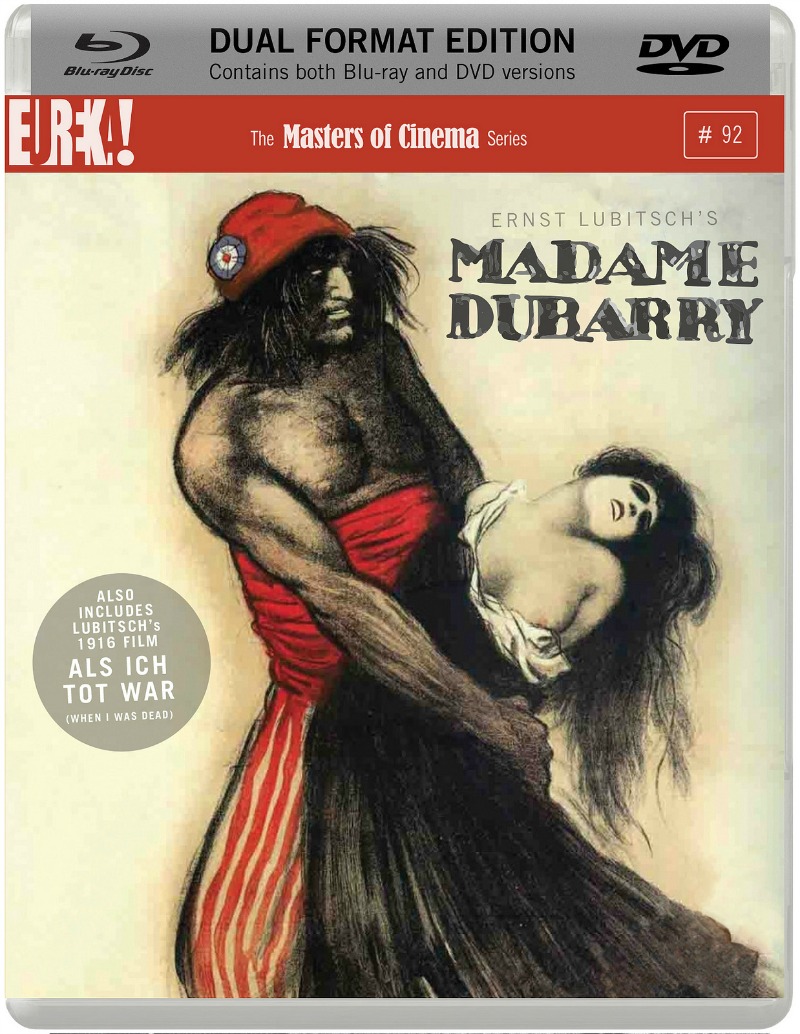

Included on Masters of Cinema’s new Blu-ray edition of Madame Dubarry is Lubitsch’s earliest surviving film, 1916’s Als ich tot war, a.k.a. When I Was Dead. In it, Lubitsch (who began his career as an actor, and directed himself in nearly thirty films) plays a gentleman who, after being run out of his house by his domineering mother-in-law, fakes his own death only to re-enter his house, posing as a servant. The extent of his wife’s determination to rid the house of him (she threatens divorce, but somewhat playfully) is, unfortunately, lost, along with various other sections of the picture, but the central drive of the piece, depicting the war between man and mother-in-law, is gracefully intact. The film is no great treasure in Lubitsch’s filmography, but as footnote inclusions go, it’s quite of a piece with what we’d come to see Lubitsch excel at in Hollywood, concerning as it does his turning inside out a certain idea of society life. There are more than a few quality laughs, and a veritable gaggle of grotesque caricatures to carry them along.

As one might imagine, Madame Dubarry fares a good deal better in the transfer department on this new Blu-ray, coming via a 1080p transfer of the film by German preservation house F.W. Murnau-Stiftung. It’s a bit on the flat side, and certainly quite damaged, but generally crisp and clear, with sharply-honed contrast (whites occasionally a little blown-out, but not typically) and powerful colors thanks to the film’s many tinted sequences. I quite incidentally ended up selecting mostly stills from the red/orange-tinted portions (which make up the bulk of the film), but Lubitsch indulges in many other colors of the rainbow throughout the picture, so one is hardly wanting for an arresting palette. Als ich tot war is not quite as enticing, and is a good deal more damaged (though far from lacking in clarity; detail suffers a bit, but not terribly, and century-old films have rarely looked better). I was generally pleased with the presentation of each.

As is typical, the team at Masters of Cinema have gone out of their way to stay true to the source, and kept the subtitles inherent to the print they received, which in this case feature the intertitles in both French and German, with optional English subtitles. For the dialogue, this is managed by simply dividing the screen in two, which makes for a fairly flawless watching experience for those who read any of those three languages. It does become a bit of an annoyance when it comes to depicting correspondence, which is written out, separately, in German and French, and presented in separate shots of roughly equal length, thus doubling the time during which such scenes would be shown. There are not too many notes to pass, however, so this is not too great an intrusion, but given its peculiarity, I felt it worth noting..

Madame Dubarry features a very fine score by Carsten-Stephan Graf von Bothmer, who accentuates Lubitsch’s determination to keep the costume drama lively; even in the film’s most dour, dramatic moments, Bothmer maintains a steady drive, refusing to succumb to something slow, even-tempered, and sleep-inducing. Aljoscha Zimmermann handles those same duties for Als ich tot war, using a very catchy refrain to retain the film’s jolly atmosphere.

The only real supplement, unless you count Als ich tot war, is the 36-page booklet, which features two essays, one on each film, by David Cairns, who does a very nice job placing the films in historical and auteurist context, focusing especially on Lubitsch’s developing visual and tonal language.

It makes for a lovely package altogether; for Lubitsch fans, this is a must-own, and beautifully complements MoC’s previously released Lubitsch in Berlin set. For others who are uncertain about the filmmaker’s grand costume dramas, I think you’ll be surprised just how “modern” this 1919 film is in its attitudes towards sex and pleasure in the royal court.

*For reasons I cannot ascertain, “du Barry” has two different spellings in this release, neither of them historically accurate. The historical person is Madame du Barry, consistent with French naming. The character within the film signs correspondence “Dubarry,” and has so been named here in keeping with the philosophy that a character onscreen owes nothing to his or her historical heritage (to say nothing of the film’s numerous, more egregious, historical inaccuracies). The title has been listed as both, but also, on Eureka’s website, as Madame DuBarry. I have utilized “Dubarry” in titling as well, in keeping with the character’s name, and the manner in which the film is referenced in the accompanying booklet.