Whenever you revisit a film you did not care for the first time, only to find yourself enthralled the second, there’s a certain impulse to say “it was like watching an entirely new film!” With Faust, as you’ll see, that may quite literally be the case.

The silent film era was sort of a Wild West time for the industry, with even the biggest productions taking a sort of fly-by-night approach to their releases. The production of F.W. Murnau’s Faust was fairly typical for its time – different versions of the film were made for different territories. With more modest films, this was often achieved by simply placing two cameras side-by-side, and the resulting films didn’t often differ considerably. Not so with Faust. Since it was such a huge production, this meant not only different edits of the material, and even different takes, but often completely different angles for the shots, costumes, lighting, and, of course, performances. The “A” material was kept in Germany, while other countries, even when they got versions prepared and approved by Murnau, received versions varying from “slightly less interesting” to “downright awful” (in. Elements of those have largely comprised previous DVD releases.

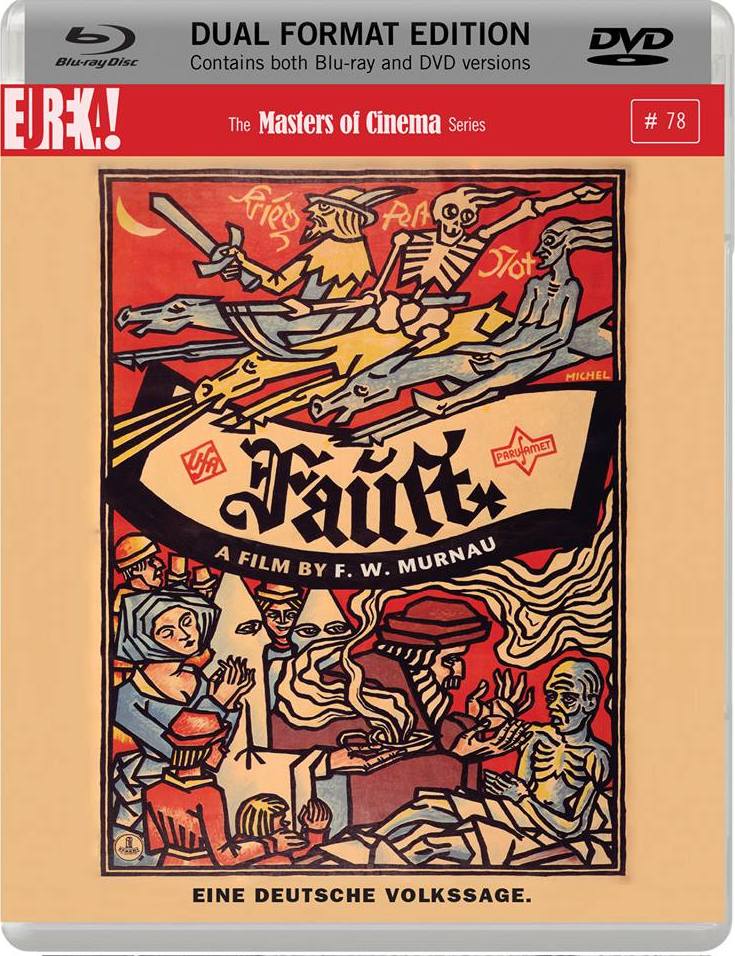

I don’t think Masters of Cinema’s new Blu-ray represents the first home video release of the original German print, but it’s certainly the first time I’ve seen it, and what an eye-opening experience it is. The editing seems tighter, the shots more dynamic, the performances a little wilder and more unwieldy, daring to go a little further, or at least invest more of themselves in it. Perhaps it was national pride. Perhaps it was a sort of xenophobic work method (“oh, who cares about that take, it’s just going to America”). Perhaps they just cared more what the people they’d actually hear from thought.

Whatever the case, the German cut of Faust really brings the too-familiar tale into sharp focus, offering a real sense of urgency to what might otherwise seem tepid and stale. With Nosferatu, Murnau established himself as a guy who could really find the sense of dread in the fantastic. With The Last Laugh, he unveiled a man’s inner desires, and contrasted those with his outer circumstances. What a perfect blend of the two Faust is. Swedish actor Gösta Ekman rather beautifully plays the character all the way through, first as the aged scientist, frustrated with his inability to help those afflicted by the plague; later, as the young man, given a new lease on his youth thanks to a pact with the demon Mephisto (an appropriately-oversized Emil Jannings). He understands the elder Faust’s physical limitations, as well as the way the soul can start to cry out when given a glimpse of what he could have.

Murnau and cinematographer Carl Hoffman (who worked with Fritz Lang several times, most notably on Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler) expertly use superimposition to layer the competing forces at work on Faust’s psyche. The town he abandoned cries out when he is miles away. The woman after whom he lusts beckons him, if only in his imagination. His potential kingdom is spread beneath his feet. Mephisto constantly lurks at the corners of his happiest moments. As with Lang and Metropolis, Murnau really had the full force of the great German film studio UFA at his disposal this time out; each frame could be a carefully-considered, elaborately-executed work of art unto itself. And Murnau was rarely shy about getting adventurous.

I will freely admit that the jump from an older DVD to Blu-ray certainly made Faust‘s many virtues stand out all the more. Masters of Cinema’s new (Region-B locked) Blu-ray is quite stupendous. Between the grain and depth, there’s a real density and richness to the image that you don’t always get, even in cleaner transfers (and this film has certainly been around the block and back). Due to the heavy grain, the stills aren’t always as inviting, but once this thing gets in motion, it really sings.

There are three whole scores available here – the orchestral, composed by Timothy Block, is probably the most obvious choice, and you won’t be disappointed for going with it. It’s big and bold and brash without being terribly ostentatious, often letting more disquieting moments simmer. The harp score by Stan Ambrose is an interesting inclusion (one doesn’t see a lot of harp in silent film accompaniment), and the results are more diverse and exciting than might be expected. Finally, there’s a piano score by Pérez de Azpeita that’s quite good, but to be perfectly honest, when you’re choosing between an orchestra, a harp, and a piano for Faust, it’s a little understandable that the piano might be one’s last choice.

Should you want to see just what a remarkable difference there is between the German version of the film and the more-widely-available export version, Masters of Cinema have not only included an excellent, eye-opening video piece comparing them (and other versions of the film), but also the complete export version! It fares considerably worse, in terms of the image quality, than the main feature, but is there if you wish to compare the two yourself. We also get a full commentary track by critics David Ehrenstein and Bill Krohn, which, while a little unorganized, still provides a quality listen. Lastly, there’s a cool German documentary on the production and legacy of the film, and a booklet with an essay by writer Peter Spooner, more explanation of the different versions of the film by R. Dixon Smith, and excerpts from Eric Rohmer’s thesis on the film, “The Organization of Space in Murnau’s Faust,” which really leaves one wishing they had some means of reprinting the entire essay.

For fans of Murnau or German silent cinema, this is an essential package. This is one of the greatest production engines in film history working at full speed, with one of its top artists at the helm. The result is as exciting and artistically ambitious as it is awe-inspiringly huge.