Federico Fellini loved a liar. Usually this takes the form of a man lying to various women about the existence of the others, often with a good deal of lying to oneself involved to maintain an illusion of, if not morality exactly, then at least basic dignity. In Il Bidone, men also have to suggest nonexistent dignity to women, but not over their philandering – rather, about the way they earn their money. That a man who understands liars should make a film about con men seems, now, only natural, but in 1955, Fellini was, with his fifth film, only just getting started.

Broderick Crawford, scrubbed and dubbed into Italian (and, fittingly, cast because Fellini liked the way he looked on a poster for All the Kings Men), stars as Augusto, the leader of a small team of men who move from remote village to remote village, concocting various wild scenarios by which to swindle reasonably large sums out of Italy’s poor. But something is brewing in Augusto. He looks worn, tired. We may not be treated to Crawford’s voice, but his figurative silence tells in all. The heaviness with which he carries himself. The sort of strained amusement he finds in his line of work; the hesitation with which he carries out every dishonest action. He’s not like Roberto (Franco Fabrizi), who couldn’t have less a care in the world except finding a way to seduce yet another woman. Nor is he quite Carlo (Richard Basehart), whose wife’s (Giulietta Masina) growing suspicions are magnifying his own reservations. He’s somewhere in the middle, trapped by routine, habit, and lack of a way out, yet increasingly disgusted by himself and everyone around him.

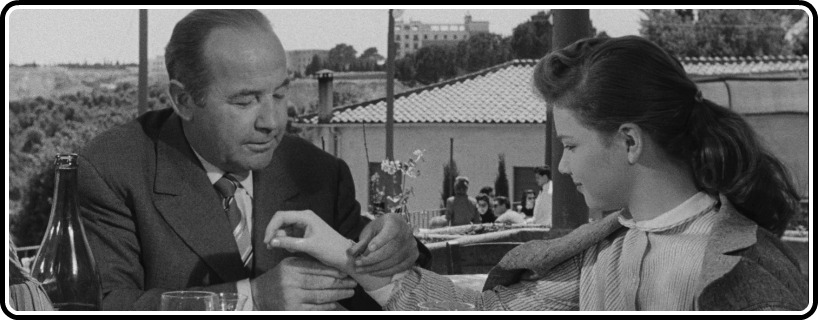

Matters are compounded when he’s suddenly reunited with his daughter. Fellini doesn’t tip his hand here, revealing what might have cast them apart. We can surmise that he simply drifted away, perhaps never even married to her mother. But Fellini and Crawford bring such rich humanity to these moment, enhancing Augusto’s soul by seeing it reflected in his daughter’s eyes – he suddenly sees himself the way his daughter does, as a man of some importance, easily able to contribute to the cost of her studies. The tragedy is that he can lie to himself as skillfully as he can his targets.

It was interesting to see this film after a year of films spotlighting con men. After all the discussion surrounding The Wolf of Wall Street, American Hustle, Pain & Gain, and many other films that spotlight, and, it has been alleged, glorify thieves, it’s interesting to revisit so many of the same themes within the often starkly moralistic realm of 1950s European cinema. As with those films, Fellini gives us a bit of the thrill of the take, but his depiction of the impoverished automatically demands we question that immediate impulse. These people aren’t just poor; they seem to be on the edge of collapse. And yet, they’re so hungry for even a modest advance in life, let alone the considerable fortunes that Augusto and his team promise, that they are blind to the blatant crime being perpetrated right before their eyes.

Fellini’s few respites of morality are, in keeping with Roman Catholic ideals, the ones who demand the least, who are content simply with a loving family and a roof over their heads. They are, even less surprisingly, all women. Fellini has a tendency to both reduce and elevate women, rarely granting them the leveling complexities of his men, yet revealing, in his inhibition, quite a lot of himself.

Masters of Cinema presents Il Bidone in its original aspect ratio, 1.37:1, in gorgeous high definition on their new Blu-ray release. All the hallmarks of 1950s European cinema – stark monochrome, density of detail in the location shooting, a sort of shimmering quality that truly represented the silver screen – are lovingly preserved, with only the occasional flaw (a few scratches) to accentuate its beauty.

The disc is light on special features, but the interview with filmmaker Dominique Delouche, an early admirer of and soon assistant to Fellini, is a whopping forty minutes long, and goes a long way towards making this release worthwhile. He recounts the early, wild days of collaborating with the filmmaker, who still had a lot to prove (La Strada was not a great success upon its premiere, and Delouche recalls congratulating Fellini and Masina while they were crying from disappointment), his way of making films often quite unique from that of his contemporaries. It’s a very cool little piece.

The booklet, as is the MoC way, adds tremendous value to the package, earnestly exploring the film’s (and Fellini’s) moral concerns without stooping to “summarize” what the director is trying to “say.” To this end, we get a review by Andre Bazin, a letter from Fellini to a Jesuit priest, as well as a short article Fellini wrote in 1960 about why his films don’t have proper endings, and how that directly informs the moral integrity of his cinema. It’s interesting to see such topics explored in the landscape of the 1950s. So much of what Fellini and others fought for in artistic representation has now been accepted and commodified. The “downbeat, open-ended” conclusion has become such an assumed aspect of art house cinema that it’s now become second nature, no longer as radical as many filmmakers think it to be. But in Fellini’s day, it was downright revolutionary, a direct affront to audience expectations and mores. It forced a question many filmmakers now only ask casually. I’m glad the team at MoC took such space to explore those ambiguities. Supporting those entries are an interview with Fellini, conducted by Delouche, and a more straightforward, though no less splendid, assessment of the film by film scholar Pasquale Iannone.