Hands Over the City begins with an image of a wealthy, corrupt developer literally placing his hands over the city he’s overlooking. This should not be thought of as a subtle film any more than subtlety should be equated with quality. Rosi’s concerns are too urgent, too contemporary, too emotional to be tempered by such banal forms of engagement. Italy’s postwar transformation from bombed to booming seems a remarkable one when looking at the films made there between 1945 and 1960, from Rome, Open City to La Dolce Vita. How did this come about? What might it indicate for the country’s future? What, or who, is being left behind in the process? And might the motivation be less one of national pride than personal fortune?

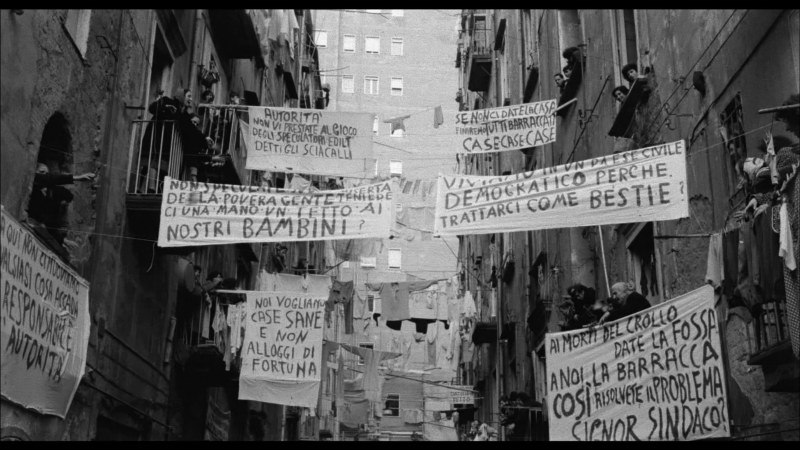

And so Rosi begins tracing the progress of one unit of condominiums in Naples, beginning with the collapse, caused by the construction crew, of a deteriorating apartment building in a working-class district. An investigation is opened, the developer – Edoardo Nottola (Rod Steiger), who is also an elected city councilman – heavily implicated; deals are traded, fortunes made, and money, above all, dictates everything. The left wing of the council, a significant presence, protests. “Why don’t you want these people to have a nice place to live?” Edoardo continuously asks, either too ignorant or too smart to admit that the poor residents he’s bulldozing could never afford the lofty accommodations he’s peddling.

Edoardo is not only bulldozing land, but colleagues, the opposition, the very spirit of a side of society that the wealthy would often just as soon see run out of town, if not outright dead. Steiger is ideally suited to this, with something of a bulldog face and total conviction in his eyes. Edoardo can contort this element of himself into calm certainty – best for placating large crowds – or total ferocity to intimidate his opponents one on one.

His hands are perhaps not those referred to in the title; they belong to anyone who moves the environment freely, as one would a game piece or a Lego set. In the credits sequence of the film, a series of helicopter shots give us a sense of the landscape, but also of the ease with which one might dominate it. Naples seems not only small, but manageable, a series of discrete units that may be moved, replaced, or extracted entirely with little consequence. Edoardo’s plan seems reasonable, perhaps even progressive, when viewed with the widest possible lens. As soon as the credits end, however, we’re plunged into the actual brick-laying, shoveling reality of making it so. The building crews seem less constructive than destructive, less progressive than invasive. It is a reality Edoardo will only glance at, assess, and escape, but which we are forced to face head-on.

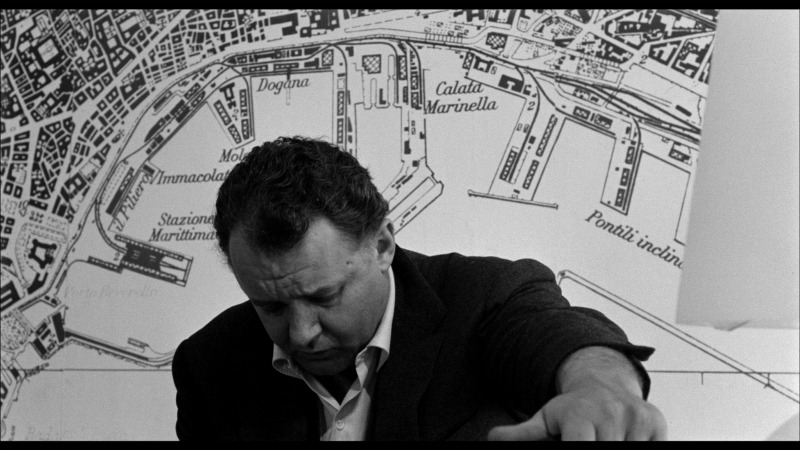

The film is constructed nearly entirely of meetings in which much exposition and detail are unloaded. It’s as fiercely paced and relentless as David Fincher’s The Social Network, a film nearly fifty years its senior; both are as much about the way something is developed as actually seeing the development. It is not altogether important the an audience glean every detail from these meetings, but vital to observe the way various factions persuade and maneuver, and their effectiveness in so doing. The film finally stops to catch its breath over an hour in. Edoardo has just been told that the best solution would be to remove himself from the upcoming elections. This is unacceptable, of course, a total betrayal of the entire reason for the enterprise in the first place – power. Sure, a land developer has power, but a land developer on the city council can accomplish anything. He is left to himself, the only scene (I believe) that depicts anyone in isolation. He surveys his impressive view from his window, a map of the city behind him reflected in the window in front of him, as though his dreams and plans are lying just ahead, but slightly out of grasp, a little ethereal in spite of their thoroughly-determined complexity.

Unlike so many modern liberal fantasy films, Rosi knows his only has power if the people lose, and he never allows us to operate under the impression that any other outcome is likely. Edoardo resembles, to cite another David Fincher project, House of Cards‘s Frank Underwood, a man who will always get his way because he is bereft of a moral compass that would in any way allow for anything else. There’s a fatalistic heart at the center of Hands Over the City, a grim realization that any moral objection one could have to the “way things are” is, at best, nice window dressing and a chance to make clear that you are not “one of them.” But “they” always win.

Masters of Cinema’s high-definition transfer, available now on a Region-B locked Blu-ray, looks really spectacular, full of depth and grain and bold contrast. The transfer retains a bit of damage from the print, but most of it is in the way of dirt and debris that doesn’t interfere with the viewing of the film. There are one or two sections where the image becomes quite soft and a little muddy, but even there, the grain structure is so strong that it reads to me as something inherent in their source. Overall, however, it is luminescent, truly gorgeous stuff. The screencaps here have been resized and compressed, but should give a good indication as to the quality of the transfer.

The only special feature on the disc is an interview with Rosi and screenwriter Raffaele La Capria, conducted by film critic Michel Ciment. Masters of Cinema rather frustratingly presents these sort of things free from context, but judging by the the look of the video, I’d guess it took place in the 90s or early 2000s. It seems to be a sixteen-minute excerpt of a longer interview, as it cuts off rather suddenly at the end, but what’s there is quite informative, as Rosi and La Capria discuss the political climate in Italy at the time (apparently the leftist party was quite new), as well as Rosi’s persistent urge to make films in Naples rather than Rome.

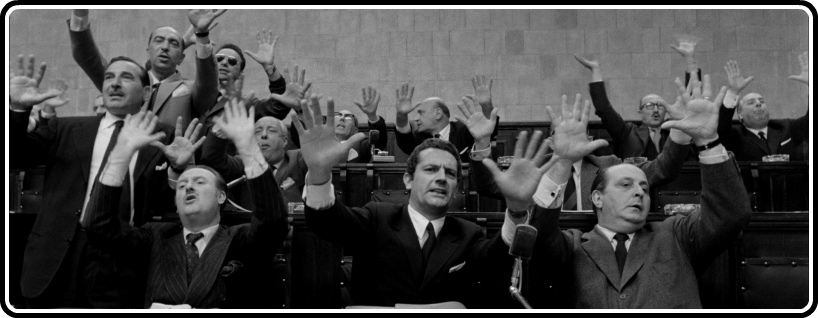

The booklet contains a single essay by film scholar Pasquale Iannone, who offers the typical approach in these things, mixing production accounts (such as that Steiger accepted the part without reading the screenplay) with critical interpretation (my favorite observation is that, due to its many scenes of gesturing Italians in meetings, “in terms of images, the film is more hands than city”). It’s a very fine piece, but unlike most of MoC’s booklets, should not be considered the make-or-break line when considering purchase.

Hands Over the City may address specific concerns of its time and place, but it speaks to issues that have remained present ever since, and are possibly simply a byproduct of civilized society. Whether we can overcome them remains to be seen, but in the meantime, it is immensely valuable to try to understand them. Masters of Cinema did a spectacular job bringing the film to Blu-ray, and I’d definitely recommend picking it up.