A tyrant is trying to force decent people off their land to take it all for himself. The decent people are willing to stand their ground, but are looking for ways to avoid violence. They’re trying to teach their children not to solve matters with guns, and if something should happen to the men in battling this tyrant, their families would be left with nothing. Yet it becomes increasingly clear the tyrant must be stopped. Along comes a young man with the skills and resolve to do their killing for them, and with no apparently attachments to anyone else to leave behind. He’s their hero, their greatest hope; they can honor him, thank him, even give him work; but we can never truly repay the way he put his life on the line so that we might enjoy our freedom.

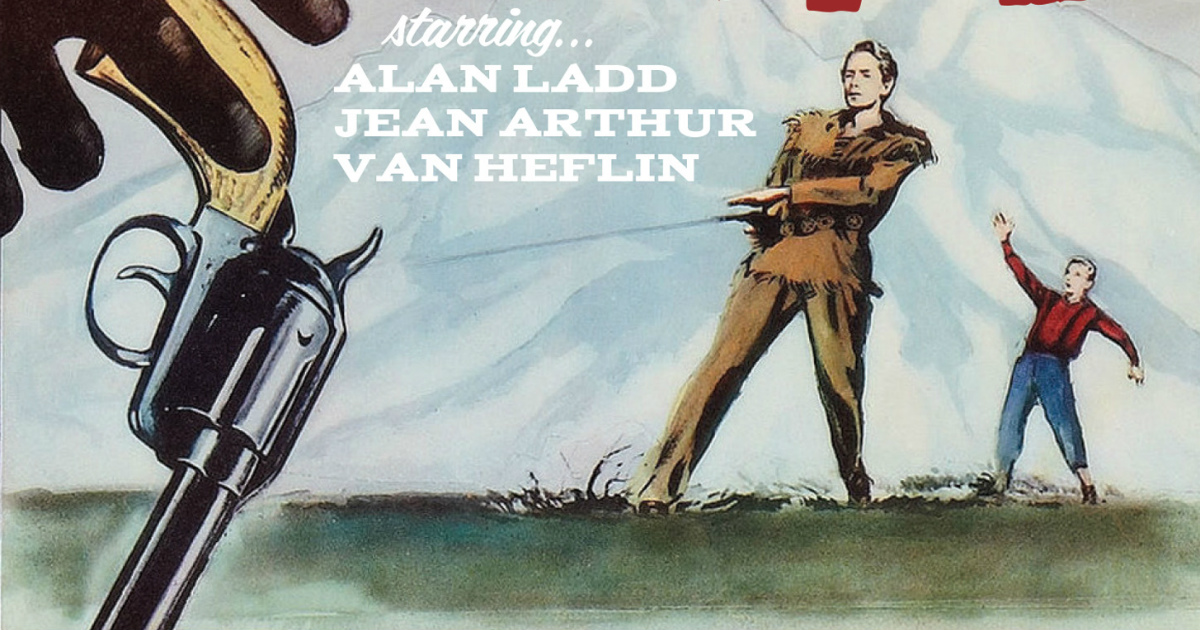

This is the plot of Shane, George Stevens’ 1953 western. It’s also the story of World War II, which ended eight years prior to this film’s release and only one year prior to the publication of the three-part Argosy Magazine story upon which the film is based. Joe and Marian Starrett (Van Heflin and Jean Arthur) stand in for the American populace who are mostly concerned with what’s in front of them – their land, their home, their future, their son, Joey (Brandon deWilde). Shane is the soldier. Ryker (Emile Meyer), the tyrant, is whatever face of fascism you want to apply. And yes, it is reductive to read a story as purely allegorical, but Shane is such an emotionally resonant fictional story because it is a true one. American moviegoers in 1953 might not be thinking all these things through, but they knew what it meant to send people dear to them off to battle, or indeed to be sent themselves. They understood what the Starretts wanted to protect, and how unrelenting the enemy can be. Younger viewers knew what it meant to idolize those going into battle the way Joey worships Shane, only to see them return scarred and restless. By 1953, they’d even seen some soldiers come home to much acclaim, only to set out on the road again, still looking for some sense of consolation.

The film was nominated for six Academy awards, winning only one for Loyal Griggs’ gorgeous color cinematography, which is extraordinarily well-represented on Masters of Cinema’s new Blu-ray edition. The film is presented in its original 1.37:1 (Academy) aspect ratio on the main disc, as well as two versions of the 1.66:1 matting (widescreen) on the bonus second disc. The first 1.66:1 comes from its original theatrical run, when Academy ratio movies were matted down for theaters that had the capacity for widescreen exhibition. This is simply a matter of lopping off the top and bottom of the picture. The second widescreen presentation was supervised by George Stevens, Jr. in 2013, changing which areas of the 1.37:1 he felt were most important. Neither of the widescreen presentations are at all compelling, with tops of characters’ heads missing and landscape scenery that never quite fits into frame. Stevens, Sr. protested against the widescreen version of the film, as he had not composed the shots with that aspect ratio in mind (as many directors in the 1950s would come to do), so the 1.37:1 version is the only one that’s really of any use to a general audience. No matter which way you watch it, though, you’ll get a robust, wonderful transfer, with strong layer colors and a density supported by the grain that makes for an image largely unrivaled in high definition. Technicolor films tend to suffer most on the road to digital, but this is marvelous, top to bottom.

MoC ported over Paramount’s wonderful audio commentary with Stevens, Jr. and associated producer Ivan Moffat. Unlike a lot of children of famous people, Stevens, Jr. really knows his stuff (his book of interviews with golden age directors is a must-read), bringing a great deal of historical research and personal experience to bear on the track, discussing how his father’s working methods informed the emotion of the movie and where the film fit into the careers of all involved. Moffat backs him up with stories “on the ground” as it were. MoC also includes a great video piece by film scholar Neil Sinyard, and the Lux Radio Theater adaptation of the film. The 36-page booklet includes a 1953 profile of Stevens by Penelope Houston, excerpts from an unpublished 1969 interview with Stevens, an eventually-scrapped prologue idea by Moffat (who went on to co-write Giant for Stevens), and an essay on the various aspect ratios. This all makes for one of the more impressive MoC releases of late, appropriate for a film of the magnitude they are presenting.

I hadn’t seen Shane before I received this Blu-ray, and I’m so pleased that it lived up to the enormous reputation it’s gained over the years. This is the rare Hollywood picture that announces itself as a major work and completely follows through, with all the grace and humor to back up the moving story at its core. Whether one views it from the postwar perspective or not, its themes of impermanence and a desire for nonviolence in a violent world are worth wrestling with, especially in such a beautiful frame as is presented here. Masters of Cinema have done a magnificent job in presenting and providing context for the film.