“Men…just the worst, am I right?” my girlfriend astutely asked after we watched Coffy. Indeed we are. For as much as Jack Hill’s landmark 1973 barn-burner is a fairly honest evocation of the struggles in the black community, it’s hard to get away from the fact that men (both specifically and systemically) are basically responsible for all the evils that take place. Even some who seem decent are corrupt. The only person you can really trust is yourself.

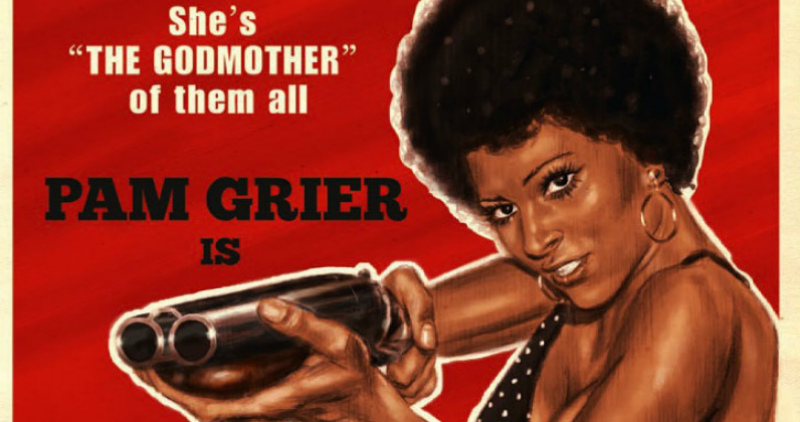

Pam Grier plays the titular nurse out for revenge on the men who got her little sister hooked on drugs. The problem with revenge, as every revenge film can attest, is that there are no simple acts of revenge. New enemies are found or created. New challenges must be met. It’s no wonder this role launched Grier to a sort of stardom. She brilliantly holds the screen, playing to men’s ego and lust to trap them, then unleashing a kind of cold fury when they have nowhere to run. Nearly any frame would send casting directors begging for her. After each encounter, she’s left shaken, unsure how she found the fortitude to do such things. She says she feels like she’s been a dream. But she also sort of enjoys it; just look at the smile that sometimes creeps in when she gets a man right where she wants him.

In the essay that accompanies Arrow’s release of this film, scholar Cullen Gallagher pulls in dozens of references, from Dirty Harry to the women in Pre-Code Hollywood films to Spaghetti Western cowboys to private detectives to femme fatales to James Bond to try to explain who Coffy is. She is all of them and none of them. She’s completely dependent on our conception of what a screen hero looks like, in part to show how malleable that concept is, and how revolutionary it can be to put a black woman in that role. But, because of that distinction, she also stands totally apart. Her vulnerability is inherited from those Pre-Code women, but unlike them, she triumphs. There is no comeuppance for Coffy. Only the weight of her deeds.

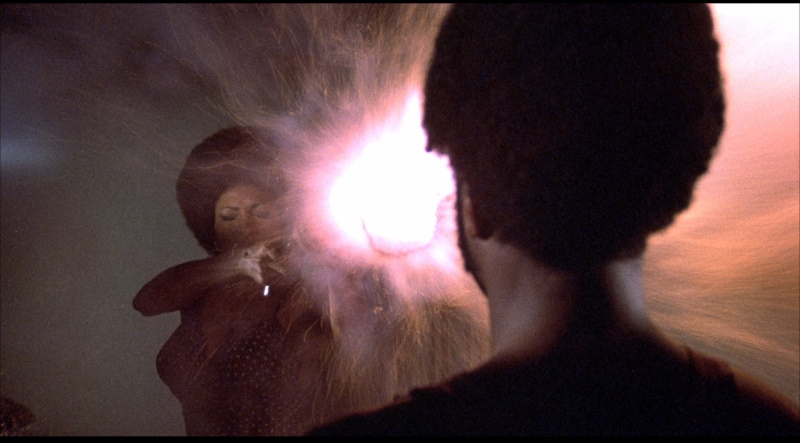

Arrow has done right by Coffy in bringing the film to (Region B locked) Blu-ray. The transfer of their transfer, on which Arrow’s James White served as supervisor, is clean and slick while still retaining the sort of grit one would expect from a 1970s color film. Black levels are solid, but not pure (nor should they be); colors pop while remaining slightly muted; grain is sturdy and ever-present. This Blu-ray, released in April, represented the first time the film was available on the format anywhere in the world. (screencaps courtesy of DVD Beaver)

They have stacked the supplements accordingly. We get an excellent audio commentary with Hill, who recounts the rather amusing circumstances that lead to the film’s production (it was essentially revenge on another producer who took a similar film to Warner Brothers) and the explosive cultural impact that followed. He’s incredibly proud of his accomplishment, but complimentary of everyone else involved in the production who contributed (noting especially that he doesn’t like to rehearse actors, so much of what’s onscreen is their inspiration). Hill also shows up in a new interview, which covers much of the same territory. Better is the new interview with Pam Grier, who’s probably talked about this film a thousand times, but still remains passionate and enthusiastic about everything she did for the film, and it for her. Also helpful for those, like me, who don’t know much about blaxsploitation, Mikel J. Koven’s video essay traces the evolution and key points of the genre. In addition to the essay by Gallagher, the booklet includes a profile of Grier by film scholar Yvonne D. Sims.

Not that a film like Coffy really needs my stamp of approval, but I will say for those expecting only kitsch from it, I was greatly impressed with the relative honesty with which the film approached its subject. It’s a sort of heightened honesty, granted; this is still a pulp film, through and through, but it’s practically a verité exercise emotionally, and that’s where it counts.