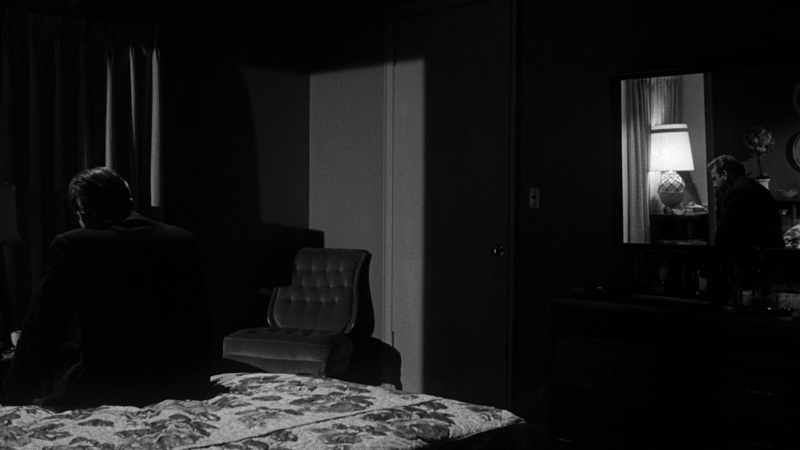

There’s a moment later on in Too Late Blues in which pianist and jazz composer “Ghost” Wakefield (Bobby Darin) throws a guy out of a dive bar, almost literally. Writer/director/producer John Cassavetes shows the scene in a wide shot, and we see the guy tumble past the doorway and into total darkness. Given that the film was shot on studio sets, rather than the location work for which the filmmaker would later be famous, this is purely a matter of economics; no need to build and light a whole street when total darkness would be totally acceptable for a night scene. And yet, that’s the whole movie, right there – one man who comes to throw everybody close to him into the abyss.

This is all to say that this is both a quintessential Cassavetes picture, and a wholly atypical one. Too Late Blues was the filmmaker’s second film. Following the rapturous response to his debut, Shadows, Paramount called him in with the hopes of getting a little bit of that “art” that was so hot all of a sudden. As things tend to go when business co-opts a burgeoning trend, they wanted the artist, but they wanted him on their terms. That meant casting Bobby Darin (who coincidentally appeared in the background of Shadows) and Stella Stevens in the lead roles and shooting in a studio. Yet the story was still his, and Cassavetes was able to fill out the rest of the cast with his own people. While he quickly disavowed the film as his fame rose on his own terms, Too Late Blues is a really stunning achievement, a pitch-black melodrama about how selfish and prideful we can all be, and how ruinous that can become. Cassavetes lets his freak flag fly a good deal, but mostly this feels like an anomaly, an example of how he could have fit into the more classical definition of an American auteur, finding an outlet for his predilections and personality within the studio system. I’ve always found the “you need to know the rules to break them” mantra a little trite (it’s a handy way to avoid actual analysis and confrontation), but for as many rules as Cassavetes broke down the road, Too Late Blues demonstrates he had a very fine handle on them as well.

Darin was a fairly inexperienced actor when he got to Too Late Blues, but he rather perfectly falls into the role. Cassavetes originally wanted Montgomery Clift for the role, which sounds like it’d be perfect, until you realize that the man was past forty by 1961. Compare this to Darin’s mid-twenties, an age better suited to a jazz man who has to first live purely on his ideals, and later on his looks. His baby face more naturally accommodates Cassavetes’s brand of man-child, his temper less palpable under his genuine charm. Plus, he was an actual musician, the singer of such hit songs as “Mack the Knife,” “Beyond the Sea,” and “Dream Lover.” He knew this world. He knew how bands interacted and hung together, both weary of one another yet inseparable. He tries to stand apart from them, moving about the pool halls and parties with a sort of anticipatory ease, completely within his element while constantly scanning the room for opportunities. But he’s only himself when he’s with them; his gleeful smile when his girlfriend gives him permission to play a round of baseball says it all. They’re all boys at heart.

Speaking of that girlfriend, it is really Stella Stevens who steals the picture. Again, Cassavetes wanted someone else – his wife, Gena Rowlands. It’s easy to see how she’d step into the role of a boozy floozy whose dreams of making it as a singer are eclipsed by her lack of talent and actual ambition. The first time we see her, her manager (one of those guys who can really do something for her, if she’ll do something for him) shuffles her into an impromptu jam session, wherein she tries to keep up with a black piano player’s scat style to rather dire results. And she knows it. And Stevens brings a real authenticity to these shortcomings, perhaps even sharing her character’s certainty that she’d get nowhere on her talent if she wasn’t drop-dead gorgeous. Too Late Blues was one of her first films, fresh off of an appearance as a Playboy centerfold in 1960. Over the course of the decade, she was one of the most photographed women, and it’s easy to see why – she commands the screen in a way not every beautiful woman can, struggling to contain a depth of feeling she can’t understand. Beautiful women have the advantage of having fun available to them pretty much on demand, and even when we meet her, Jess (Ghost calls her “Princess”) is perhaps feeling the limits of how much fun one can have when everything else in your life is a crushing disappointment. Her eyes are magnetic, barely engaged in a series of rooms offering the world and delivering very little.

When she joins the band, the writing is on the wall. The ego that Ghost throws around will not stand up even alongside someone who asks as little of him as Jess does. He’s content to play in parks and for charities because they let him play what he wants. The other boys want nightclubs and records, but Ghost feels he’ll have to give up too much of himself. The easy comparison to Cassavetes’s own career is right there for the taking, though, indeed, the filmmaker’s own decision to strike out on his own seemed to work out a good deal better than it did for Ghost, perhaps because he realized, before his fictional counterpart, that it’s a lot easier with some help from your friends. But the kinship is there, not only in circumstance (which would be simple, and possibly self-glorifying), but behavior as well. Ghost is alternately admirable and pathetic, standing up for his art only to pout when that doesn’t yield him success; wooing the girl in the classiest way possible, only to turn on her in an instant when self-doubt creeps in. It’s a potent creation, and given the frequency with which this character type pops up in his films, one he understood in a deep, personal way.

As a result of taking a more formal approach to his storytelling, Too Late Blues is one of the most classically beautiful films in Cassavetes’s filmography, and it is extremely well-served by Masters of Cinema’s new (Region B locked) Blu-ray release. The aforementioned, abyss-like shadows do indeed seem to extend forever into inky darkness. The image is beautifully crisp, with a good helping of grain that lends it gorgeous texture. A few instances of damage remain, but it is largely a clean print. A slight hiss accompanies the audio, but it hardly distracting.

The only disc supplement is a very good, 17-minute video interview with film scholar David Cairns, who discusses the film’s place in Cassavetes’ career and its finer qualities. He doesn’t quite give the film enough credit, in my opinion, but it’s a nice overview. A similar approach is taken by scholar David Sterritt in his essay in the accompanying booklet, but each have enough going for them to not cancel the other out. The booklet is rounded out by a contemporary profile of Cassavetes, an excerpt from composer David Raksin’s 2012 autobiography, and a 2007 interview with Stevens, in which she gives a rather boring series of answers (“everything was great all the time!” is the gist), until she gets to her own reflections on the emotional toll of the character, as well as a story involving Bobby Darin getting an erection. Good stuff.

Too Late Blues may be compromised Cassavetes, but those compromises seem have, uniformly, made for a much better, more interesting film. Masters of Cinema have put together a fantastic package in which to present it. It’s an easy recommendation, especially for fans of the filmmaker or those interested in the ways Hollywood tried to present counterculture in the early 1960s. But it more than holds its own as a discrete piece of drama.