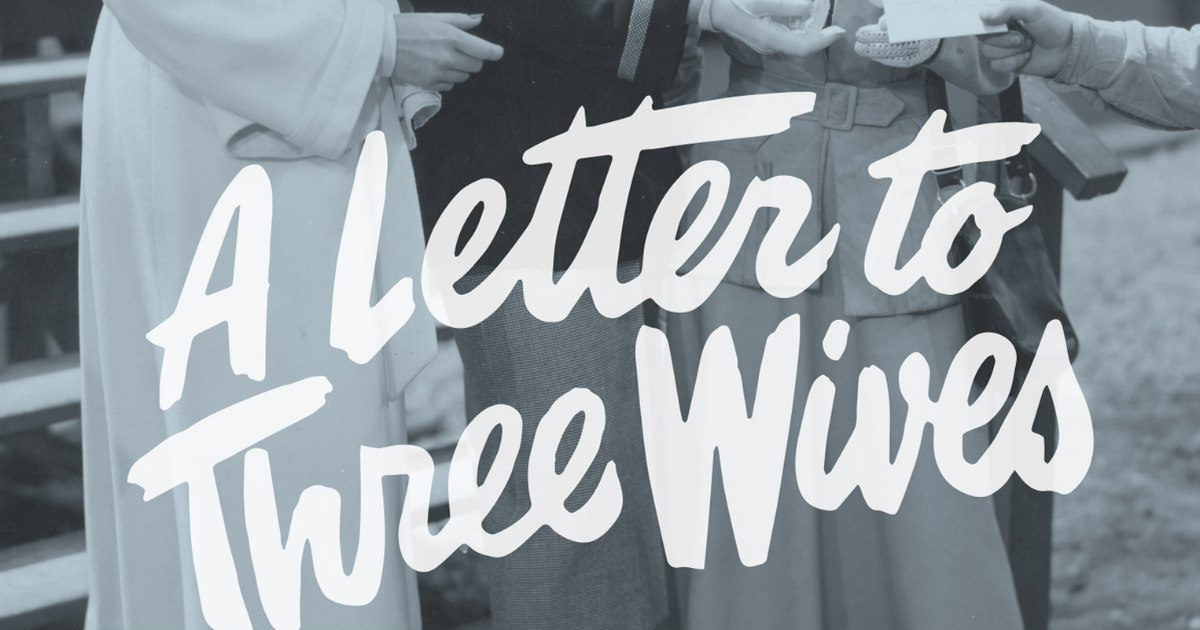

Like so many great American films of the era, A Letter to Three Wives has a touch of trash at its core. Writer/director Joseph L. Mankiewicz crafts well-rounded characters, thoughtful explorations of class via small-town postwar America, and snappy dialogue to spare. But this is still a story that really kicks off when three women receive a letter from another claiming to have run off with one of their husbands, timed to a daylong excursion where she knows they can’t do a damned thing about it. Not that there’s anything wrong with that at all.

The bulk of the movie takes place in flashback, as each woman reflects on the more tumultuous moments in their relationships, and why each husband would be motivated to abandon ship for the highly-desirable Addie Ross. Addie seems to have gotten around often enough to have gotten around to those same husbands in some capacity. It’s a small town, after all. Everyone knows everyone; sometimes too well. The wives are Deborah (Jeanne Crain), Rita (Ann Sothern), and Lora Mae (Linda Darnell); a farm girl, a soap opera writer for radio, and a gold digger, respectively. Those designations paint them unfairly, I’ll admit, but again, such quick character sketches are inherent to pulpy romance, and go a long way to efficiently outlining character and conflict.

Deborah met her husband, Brad, in the Navy, where they were more or less equals. If only she knew she was marrying the prom king, diving fully into a social circle she barely understands, let alone is able to navigate. Rita and hers, George (Kirk Douglas), were high school sweethearts, and bicker the way people who have been together for too great a portion of their lives tend to – they mean it, but it’s all in good fun. She makes more at the radio than he does at the school, to boot. Lora Mae, meanwhile, saw Porter (Paul Douglas), a rather wealthy businessman, first as merely her way out of a house that shakes when the train rumbles by, but a few years of marriage can endear you to all kinds of people.

Now then, Mankiewicz (working from a slew of screenplays and treatments by at least four others; only Vera Caspary is credited, with the always-enviable “adaptation”) makes one untenable, but understandable, structural choice – we never see Addie Ross. She is portrayed in omniscient, catty voiceover by Celeste Holm, rather a lot to ask of someone who had already won an Academy Award (in 1947, for Gentlemen’s Agreement). She does a heck of a job crafting the idea these women have of Addie – her voiceover could be as much their projection as her perspective – but it still lets the audience thoroughly detest her without the natural avenue of empathy a face would provide. She can simply be “That Damn Woman,” allowing the women in the audience to fill in the blank with whomever has filled that role in their own lives. It’s a smart commercial move (and makes for good trash), but an uneasy moral one.

Otherwise, the picture is a pleasure, spectacularly well-detailed and full of good humor and heart. Everyone has something that makes them a little pathetic or pitiable – Deborah her awkwardness, Rita her desperation to impress, Brad his wandering eye, George his elitism; Lora Mae and Paul each other – but not in some grandly developed, tragic way. Just a touch of fault they can’t disregard, nor can they let stand in the way of loving one another. And these blemishes endear them; who hasn’t felt woefully out of place, or occasionally superior, or jealous, or had a touch of spite mixed in with unyielding love? And while the women in the audience may have some woman they passively hate to stand in for the absent Addie Ross, surely more than a few men see in her “the one that got away.” In the otherwise-safe context of a romantic drama reaffirming existing matrimonies, it’s nice to remember that maybe the road untraveled is best left that way.

A Letter to Three Wives won Mankiewicz his first Oscars (for Screenplay and Director, both of which he’d repeat the following year with All About Eve, which would additionally net Best Picture), and well deserved each was. Mankiewicz is understandably considered a writer first – so many words in his movies! And what words they are! But as David Cairns expertly outlines in the essay accompanying Masters of Cinema’s new Blu-Ray release, he hardly just sat back and watched his words brought to the screen. In addition to Cairns’s examples (which I’ll leave to you to discover on your own), I think especially of a beautifully-wrought moment of both blocking and cutting. During Rita’s flashback, her almost-painfully lowbrow boss reaches to turn on the radio to hear their latest soap, in the process breaking George’s rare Brahms recording. This was the analog era, kids – sometimes when that record’s gone, it’s gone. Mankiewicz and editor J. Watson Webb, Jr. (they knew how to name ’em back then) cut right as the record’s broken, and Douglas holds on the moment when his outstretched arm, too late to reach the radio before Mrs. Manleigh (herself acutely named) wrecks it, has to resist redirecting the energy to strangle her. It’s bad enough to lose a Brahms; to lose it to this woman is leveling. With this image, in this montage, Mankiewicz conveys a monologue’s worth. That’s direction.

The image quality in Masters of Cinema’s new (Region B locked) Blu-ray might best be described as “professional.” Not that this is a terribly dynamic film in terms of lighting or anything, but it’s nevertheless a nondescript transfer; if there was any damage at all, I never noticed it, and the film has been stabilized and rid of anything in the way of fluctuations. Grain is perfectly consistent. There’s nothing terribly wrong with it (maybe it’s a little soft), but there’s nothing really alive in it either. I am unsurprised to learn it is essentially the same master that 20th Century Fox used for their own U.S. Blu-ray release, as it has the familiar studio archive touch of total competence, but little inspiration. (screencaps courtesy of DVD Beaver)

MoC ports over Fox’s excellent commentary track with Mankiewicz biographers Kenneth Geist and Cheryl Lower, and son Christopher Mankiewicz. Though recorded separately, they’ve been edited so well together, and build off of one another’s observations so intricately, that you’d swear at times that they wrote, rehearsed, and performed the whole thing together. They also bring over a short archival snippet of Movietone News, with footage from the 1950 Academy Awards. They step up the package by including two radio adaptations – Screen Guild Theater and Lux Radio Theater – as well as a booklet with the aforementioned essay by David Cairns.

I hadn’t seen A Letter to Three Wives before receiving my review copy, but, based on this and All About Eve, can easily see what made Mankiewicz so popular in these years. Here, he really captured the sort of uneasy peace people had settled into with the war well over and their lives seemingly established. Neither tragedy nor comedy, it provides the kind of warm, cheering drama that can be recommended to damn near anyone who watches motion pictures. MoC duplicated the key supplements from the Fox edition, while adding a few worthy entries of their own, making it, to my thinking, the definitive edition of this American classic.