While many directors try to elevate their cultural standing by moving away from schlocky genre films and toward something a little bit more “respectable,” Kaneto Shindo did precisely the opposite. Appearing on the international scene with the rather directly-topical Children of Hiroshima, the first Japanese film to deal with the subject, he came back from the brink of bankruptcy with 1960’s The Naked Island, a meditative drama about the daily rituals and back-breaking work of poor rural farmers. He made two more films dealing with social issues, then really shook it all up with 1964’s Onibaba, a supernatural erotic thriller for which social issues only accounted for a fraction of the topics and visceral emotions mixed in there. Bereft of all the politeness that usually accompanies films of wide acclaim, it was a vast departure – lurid, pulpy, and genuinely depraved.

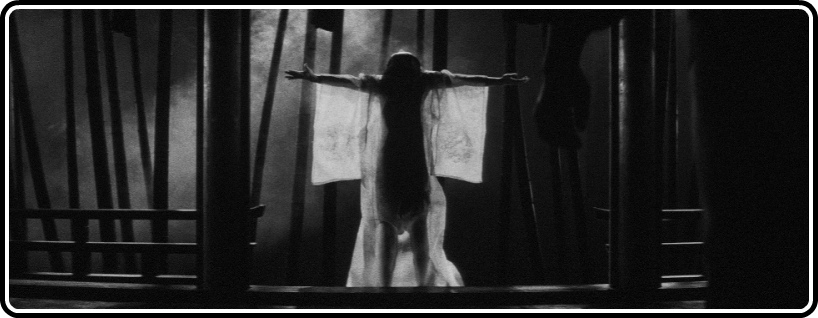

Kuroneko is not quite as audacious, but its very premise is decidedly closer to that of genre entertainment than award-winning drama. In its mostly-wordless first third, we follow a woman and her step-daughter (a relationship that also provided the foundation in Onibaba), who are raped and murdered by wandering soldiers, their house burned to the ground and possessions either stolen or destroyed. They return as ghosts with feline attributes, pledged to seduce and murder any samurai that come their way, an arrangement that works out great for them until the local governor sends one to specifically hunt them down. That samurai? The woman’s son, and step-daughter’s husband.

What begins as a haunting, sexy revenge piece comes to morph into something much more complicated, a vision of loss, mourning, and resurrection that’s much more akin to Ugetsu or Vertigo than, say, Evil Dead, though it is notably not bereft of that latter filmmaker’s more wild embellishments. Shindo’s particular elegance, his love of lingering shots and elliptic editing, is hardly undone by the wilder scenes of wirework, in which the ghost women leap across the screen in every direction, attacking their prey in the throes of passion or the dark of the woods, though the collision of the two does create a slightly jarring effect when viewed as a whole. Still, Shindo’s masterful transitions separate each nicely, and when the two disparate elements come together for the thrilling, and entirely mysterious, climax, they feel totally of a piece because he’s established the styles so neatly.

I don’t know where Masters of Cinema is getting these transfers for their Shindo films, but all three of them look astounding. Looking at DVD Beaver’s comparisons (their screencaps are also used here), there is a marked difference between what MoC provides here (on a Region-B locked Blu-ray disc) and what Criterion released on Blu-ray two years ago. MoC’s transfer is much darker, losing some detail in the darkness but gaining tremendously in the light (and Shindo is not shy about his contrast). I don’t have direct experience with the Criterion in-motion, but I can say that the MoC transfer is really great, reenforcing the mood and atmosphere by letting the darkness nearly overwhelm us. Beyond that, it is virtually flawless – grainy, but not noisy, crisp and scrubbed absolutely clean, yet still maintaining the vibrance of a film print. It has a wonderful density and sense of depth, much appreciated for the film’s many wide shots. Just gorgeous all around.

The Criterion edition does have MoC beat in the special features department, as MoC only provides a theatrical trailer and another stellar booklet. This actually lines up very well with their other Shindo releases, providing an excerpt of a longer interview with the director that is completed by those other two, creating a similar consistency to that of their two Claude Chabrol releases from a couple months back. That, and the essay by Doug Cummings, both add much to the film, though it’s unfortunate that this did not come with a commentary, as those did; Shindo is an exceptionally sharp filmmaker, exhibiting a thorough understanding of what each shot accomplishes, and it’s great to hear his scene-by-scene perspective.

Still, if you don’t already own the Criterion, or want a different perspective on it from the transfer, this is worth picking up. MoC has single-handedly forced my introduction to Shindo, and I couldn’t be more thrilled – his filmmaking is so refined, so simply profound, to watch his films is to consider the rest of the cinematic landscape and say, “hey, what’s stopping everybody else anyway?”