Kelly Reichardt’s triptych film Certain Women is adapted from three short stories by Maile Meloy, and retains the feeling the form is so effective at evoking. Spare on plot, they isolate moments from people’s lives. Some of are overtly dramatic (an early standoff with a rifle perhaps suggests more exterior conflict than the rest of the film will yield), but most of are fairly mundane. But they leave one feeling as though some untapped perspective or desire has been revealed, and we’re not yet fully prepared how to take stock of it.

As there are three stories to account for, I don’t want this review to turn into a complete synopsis; and as the first and third sections have generated the most discussion over the past year and a half, the second story, led by Michelle Williams. When I first saw the film at Sundance 2016, the immediate consensus was that it was the weakest, that it didn’t really dive into interesting drama or reveal all that much by the end. Compared to the struggles of a female attorney (Laura Dern) as she asserts her authority to her male client (Jared Harris), or the unrequited romantic stirrings of a rancher (Lily Gladstone) for a visiting young attorney (Kristen Stewart), one woman’s mission to buy some rocks from an old man certainly seems significantly less compelling.

It’s the one that stayed with me most though, and when I revisited the film upon its general release that October, the one that seemed the most developed and mature. Whereas the first and third stories at some point state a large portion of their goals, this one never does. It takes as read that we’ll never quite say what needs be said or do what we want the way we want to. We can hope to clumsily lurch toward a few modest goals that bring momentary satisfaction. Williams plays Gina, the mother of a teenager (where does the time go, amirite?), whom she’s dragged on a family glamping trip and whose patience will be further tested with a trip to see a lonely old man named Albert (René Auberjonois). He’s sitting on some sandstone without much an eye with what to do with it. She has an eye on it for the house she and her husband Ryan are building from scratch.

All the drama takes place in the corners of lines. It’s the way Gina can only affect friendliness for personal gain, and the lonely position that puts her in; the unease that sets in the moment she leaps in front of Ryan in bringing it up to Albert. Reichardt has a natural way with tension, so that even a stationary shot of Ryan backing out of a driveway turns riveting. Unlike the first and third stories, the stakes never reach life or death, or a question of emotional fulfillment. If they can’t get the sandstone from Albert, they’ll figure something else out. The tension lies in feeling out of touch in one’s own life, the meager acts we take to reclaim it, and the extent to which we toss the needs of others aside in so doing. It’s a masterful piece of short fiction inside a masterful film.

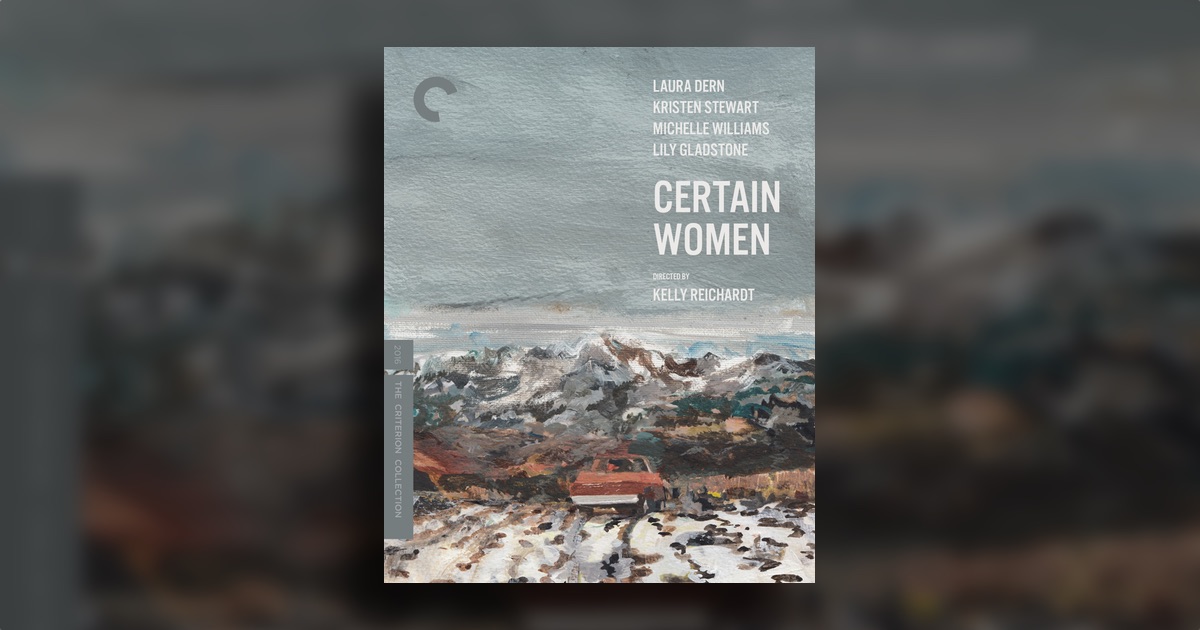

As with all of Criterion’s contemporary IFC releases, not a lot of work was required to bring the film to Blu-ray. I imagine compression could have been a little tricky to negotiate, as it’s clearly shot on film and has more hefty grain to it than most modern works. But given its modest 107-minute running time, I doubt many complications arose. Whatever the case, it looks extremely good, equally as pretty as the projection at Sundance did, and marginally better than I recall it looking at my local art house when I saw it there. Reichardt’s soundtracks are just as important in settling or raising certain tensions, and everything sounds crisp and fresh there as well.

Aside from the consistency of transfers, we can also count on Criterion’s IFC releases to be fairly sparse on supplements, and this release does not disappoint on that front either. We get three fifteen-minute interviews; one with Reichardt, one with Meloy, and one with producer Todd Haynes. Short though they may be, they each have valuable insights into the process of making the film and Reichardt’s general approach to filmmaking. As a big fan of Reichardt going back to Old Joy, I confess I was most taken with Haynes’s interview, as he basically just uses the time to gush about how much he loves her style and films. Film scholar Ella Taylor also provides an insightful essay in the booklet.

I’m quite pleased with the package all around. The film has been on my mind pretty constantly for the past year and a half, and I’m grateful for the excuse to keep it there for a good while to come.