Every film creates a world, and every filmmaker a universe. Some prove uninhabitable. Given the rarity of Kiju Yoshida’s films, the grandeur with which Arrow Films is presenting them, and the way they were talked about – three films “united by their radical politics and an even more radical shooting style”; “bleak but dreamlike” – I dove into this set quite curious and excited. I found Yoshida’s universe to be one of the most tumultuous I’ve yet encountered. Even oblique films tend to carry with them a bit of poetry and emotional momentum. I think especially of films like Last Year at Marienbad, The Mirror, Goodbye to Language, or Flowers of Shanghai, all of which are so exciting and riveting despite my not initially knowing what they were really about at all.

At least two of the films in this three-film set gave me no such pleasures; Coup d’etat and Heroic Purgatory are unbelievably dense, and totally uninviting. Leaving them, I felt not the rush of the unknown but the deadening of my sense. More on them momentarily. Eros + Massacre (1969), the centerpiece of the collection, proved a good deal more interesting, at least in its longer, 220-minute form (I’ve only skimmed the shorter, 169-minute theatrical release; both are included in this release). Like a lot of the Japanese New Wave, it is concerned with the intersection of an exploding youth culture and the Japanese traditions that culture sought to decimate. Yoshida, who cowrote the screenplay with Masahiro Yamada, addresses this divide more directly than most, situating the bulk of the action – a loose biopic of early 20th century anarchist Sakae Osugi – within the framework of a pair of radical students researching his life and work in 1969. The two timelines interact in parallel ways that eventually intersect.

Osugi was a proponent of free love, a topic which audiences in 1969 would be a lot more open to and familiar with than Osugi’s contemporaries. Much of the late-1960s cinema into the 1970s tested the limits of these ideals. It is one thing to declare attraction independent of devotion; quite another to see one’s lover with another. As Osugi’s own ideals disintegrate around him towards the end of Eros + Massacre, he insists that the culture – which includes himself – simply wasn’t ready for free love, that it was too soon. The students in 1969 are finding that they too might be too soon to the grand bargain; will such arrangements ever be palatable? It can’t just be for the sake of drama that so many films come down against it. Virtually every French film of the era was about this subject in some way. American films were just starting to pick up on it. Most found agony in it, despite the initial thrills. What distinguishes these radical filmmakers, Yoshida especially, from their later moralistic counterparts who tsk-tsked the free love era is a complete indulgence in it. Yoshida doesn’t look down on or even pity Osugi for his failures. He’s curious about them. He wants to see Osugi follow the logic all the way down the line because…what if it works? The ideal would completely upend modern culture.

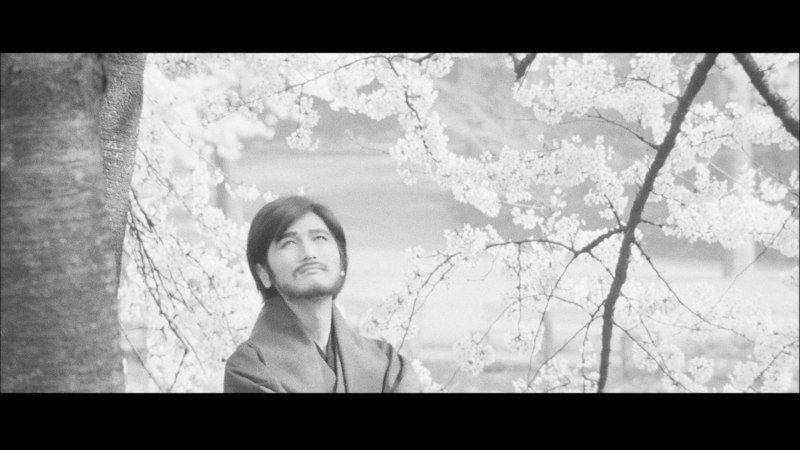

Amidst it all is an investigation of the free press, of which Osugi was a natural proponent, especially after author Noe Ito (later one of Osugi’s lovers) used her feminist magazine Seito to criticize the police for banning Osugi’s own newspaper. Osugi flirted with several ideologies in his road to anarchism, including socialism and, somewhat more permanently, Christianity, of which – like most radicals – he practiced a sort of adjusted, self-made version. But Yoshida is primarily interested in Osugi’s sex life, and the effect it has on his wife, Ito (played by Mariko Okada, Yoshida’s wife), and other lover Itsuko Masaoka (Yuko Kusunoki) (as a side note, the fact that I can’t verify or discern whether Osugi’s wife is portrayed in the film at all is some indication of Yoshida’s ability to convey a clear narrative, or interest in so doing). This leads to the sort of high drama scenes one might expect, including a much-publicized stabbing, all of which Yoshida plays with a certain chaotic sharpness. The characters may go any which way, but his camera never will. Far from ensuring a certain degree of safety, though, he establishes quite soon into the picture that his camera will not be there to capture everything; if something should happen just out of frame, so be it. Yoshida speaks of this as a way to cause the audience to not trust any given character, and it additionally reminds us of the limitations of looking at anything from only one perspective. It also doesn’t hurt that every single frame in this thing is unbelievably gorgeous – smartly framed, beautifully lit, and just utilizing the hell out of the anamorphic widescreen format.

There were concerns raised that the general appearance is too blown-out to be acceptable, but rest assured, that’s how Yoshida wants it, and seeing the film altogether, the lighting decisions make a certain degree of aesthetic sense. At the very least, it wasn’t applied to every shot, so there were choices being made.

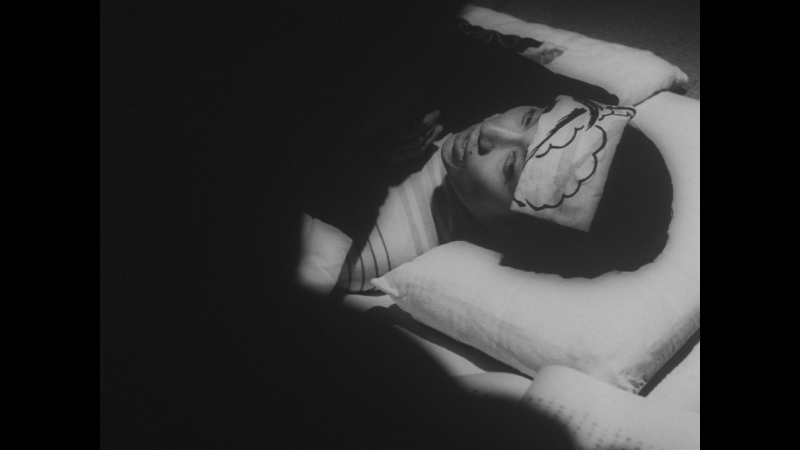

That aesthetic rigor, and the ferocity of performance style, is potentially the only virtue left over from Eros + Massacre as we move into Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’etat. I fully admit to understanding neither, and finding the experience completely unenlightening. I’m also sure this is completely my fault. But be that as it may, there’s nothing I could tell you about either film that doesn’t come from somewhere else. Purgatory gets at a bit of what its title suggests, giving us a world in which all these radicals end up trapped between life and death as we consider the true impact of their contributions. It’s plenty surreal enough for that approach to hold water, but I just could not follow the whole thing closely enough to say. Coup d’etat was even more hopeless; it was Yoshida’s final film, and while it feels very much like a summarization and capstone of sorts, I could not say to what.

I’d be interested to revisiting both of these films down the line, but at present, there are only so many hours in the day and I haven’t the time to do so. I genuinely hope there are enough viewers who appreciate these films, for Yoshida’s voice is so distinct – even in the context of one of the wildest mainstream film movements in the history of the medium – that I am glad merely for the fact of their availability and the care in their presentation.

Eros + Massacre looks best in its new high definition transfer, the overblown whites really working elements of your monitor that you don’t see often explored, with excellent clarity, depth, and grain texture to go with it. At 220 minutes, plus some light supplements, it can’t have been easy to compress onto Blu-ray, but Arrow has done a really remarkable job. Heroic Purgatory, which shares a disc with Coup d’etat (each of those films runs just under two hours), looks nearly as good, taking advantage of a much darker palette, but not sacrificing depth or detail along the way. Coup d’etat looks worst of the bunch, perhaps a little overcompressed or just not as carefully restored or preserved. The presentation is fairly flat, the contrast not terribly bold, and damage more immediately evident. It’s perfectly acceptable, but quite a striking transition after the other two. (screencaps via DVD Beaver)

Film scholar David Desser, author of Eros Plus Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave, does the heavy lifting on the supplements, recording select-scene commentaries on each film in addition to filmed interviews. While his comments were invaluable in just letting me know what the hell’s happening at any given moment, I can’t say I found them terribly enlightening or insightful. They felt like the sort of observations one can get away with making at the fore of study in a certain arena, but thirty years into the inclusion of scholarly supplements on home video, the need to cut deeper is more fiercely felt. Luckily, that need is better fulfilled in the 80-page book that accompanies this set, with essays by Desser (who organizes his thoughts better written, but is also only tasked here with a general overview of Yoshida’s career) and fellow scholars Isolde Standish and Dick Stegewerns contributing insightful, well-researched essays on the films and filmmaker. Yoshida himself also shows up on the disc to introduce Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’etat, and a thirty-minute documentary on Eros + Massacre includes insights from Yoshida and film critics Mathieu Capel and Jean Douchet rounds out the set quite well.

The films weren’t entirely for me, and it would be tough to recommend buying the whole set based entirely on the affection I have for Eros + Massacre. But not everything has to be for everybody. Based on the responses to the set, I’m far from alone, but I’m glad those who do love these films get a set as well-produced as this through which to experience them. It once again shows Arrow’s near the top of their game. The transfer for Coup d’etat was a bit of a disappointment, but those for Eros especially and Heroic Purgatory are plenty strong enough to make up for it. Supplements are a bit mixed, but do function as helpful introductory material. Word has it this set has already sold well enough to justify more obscure Japanese releases, and I can’t wait to see what Arrow digs up next.