There are a few reasons a home video label might decide to group a series of films into a box set. Sometimes it’s as simple as bundling lesser-known titles with guaranteed sellers. Sometimes the films fit a thematic concern, or a particular period of a director’s career. Best is when the films serve to embolden one another, so much so that it becomes difficult to imagine one apart from another. Masters of Cinema’s incredible new box set, Late Mizoguchi, is a mixture of all of those approaches, though its greatest mission is also the simplest – making these films available in pristine condition, and encouraging, by limiting the number of sets they produce (only 2000 will ever be made), the more impulsive among us to snatch it up and suddenly be exposed to a range of cinema we might not have otherwise. The films collected do not add up to a whole in the way that Criterion’s recent Rossellini/Bergman set does, but as individual, discrete works, they are magnificent.

I’m splitting up my review of this set into two pieces – there are eight films to discuss, after all – so this time around, we’ll be looking at Oyu-sama [Miss Oyu], Ugetsu Monogatari, Uwasa no Onna [The Woman in the Rumor], and Chikamatsu Monogatari [A Tale From Chiamatsu]. Like most Criterion devotees, I had seen Ugetsu already, and viewing it again made the best case possible for the necessity of owning this set. It hadn’t even been that long since I saw it – maybe two years – and yet my appreciation and affection for it grew tenfold in rewatching. Where first I found it perhaps slow and labored, I now found it rigorous and invigorating, for all the reasons one is likely to have heard. It’s far and away the most fantastical of the four (which is to say it involves fantasy at all), and Mizoguchi treats such departures from reality as just that without sacrificing the emotional stakes they bring about. Even when something isn’t “really happening,” it’s still happening, and the decisions that one character in particular makes has even worse consequences than if he had made a similar, more grounded run from the squalor of his existence.

The film can be quite simply read as a damning portrait of greed and hubris, and Mizoguchi has quite a handle on translating a fable to cinema (a more difficult skill than it may appear, for as natural as the two seem to fit), in part perhaps because Mizoguchi’s cinema is swimming with fable, parables, archetypes, and legends. His stories have the deliberate engineering one might find in more recent efforts by Joel and Ethan Coen – A Serious Man and this year’s Inside Llewyn Davis come especially to mind – that convey the feeling of an entire world turned against you, even as his basic humanism is perhaps more pronounced. But like the Coens, he spares his protagonists not at all in slowly bringing to bear all the worst that humanity and nature have to offer, offering only the comfort in knowing that even when things seem like they can’t possibly get any worse, then absolutely can.

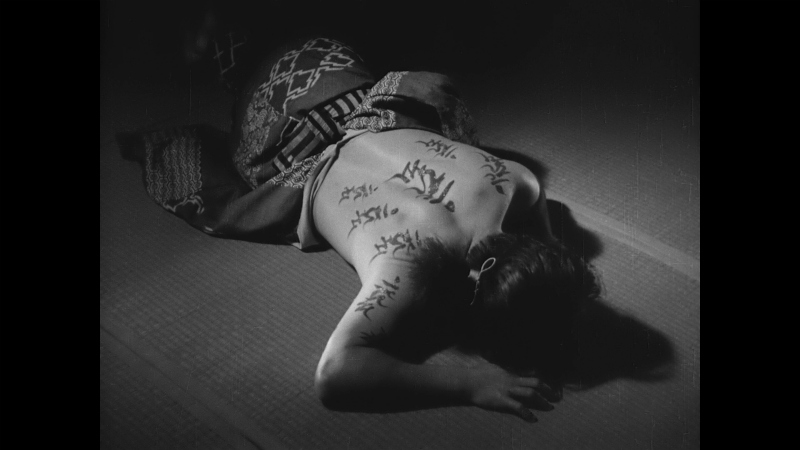

In Chikamatsu Monogatari, for example, a misunderstanding sets a merchant’s wife and his employee on the run, believed to be having an affair, only for their time on the lam to cause just that. Released in some parts of the world as The Crucified Lovers, Mizoguchi twists the familiar “forbidden love” trope, making the very laws that punish such an act the same that cause it. From there, it’s a classic unstoppable-force/immovable-object situation, which Mizoguchi wrings for every ounce of tension and despair he can muster. For those who have maybe had trouble finding an entry point to the director (I can relate), this would be a perfect place to start, as it’s far more plot-driven than any of the others I’ve seen, even outright “entertaining.” Mizoguchi’s depiction of something essentially good – unbridled passion and love – amidst repressive and authoritarian forces is the sort of eternal story, and as with Ugetsu, he never releases the personal and specific in also telling a story that is largely symbolic and universal.

Quite the opposite effect is felt in Oyu-sama, which is so small and personal to nearly be stifling. It tells the story of a meek bachelor whose choosiness in a potential bride has caused great concern, but who finally gets a breakthrough when he falls in love not with the latest candidate to come through his doors, but her widowed sister-in-law, who has overseen her dead husband’s sister’s own series of would-be suitors, never approving of a one. Her dedication, verging on dependency, for this tie to family is relinquished when she, too, falls for the suitor – both recognize that societal customs would make them outcasts should they act on their passions, so they use the bride-to-be as a sort of vessel, a way to spend time with one another without raising too many suspicions. Incidentally, the bride is completely fine with this arrangement, right up to the point when, you know, she’s not.

Mizoguchi builds some fine scenes out of this set-up, especially a vacation in which a server remarks on how nice it is to see a married couple so clearly in love with one another, only about the wrong couple. Kiyoko Hirai is not precisely the protagonist, but because the emotional fulcrum of the story rests upon her, she really draws the most out of these moments, giving expressions that must communicate happiness, contentedness, jealousy, heartache, and regret all at once. She is not the finest actress to grace Mizoguchi’s cinema, but almost because of her occasional clumsiness, her performance is all the more affecting. If only the rest of the film, often too polite and reserved for its rather bawdy premise, had the same charm.

Where Oyu-sama‘s specificity was its undoing, Uwasa no Onna actually opens up as a result of same. Uwasa no Onna concerns a young woman whose life priorities are wildly rearranged after a suicide attempt spurred on by a broken engagement. Yukiko is not merely some lovesick schoolgirl, though – it was the revelation of her mother’s profession, as the owner of a brothel, that caused the man to leave. One may assume future prospects may do likewise. Luckily, she’s in good hands upon returning home. Not only does her mother constantly put Yukiko’s interests first, but she has insisted that the young doctor whose career she is overseeing direct a great deal of his attention towards her, which ends up remedying many of Yukiko’s problems, if not precisely how her mother intended. After all, Hatsuko’s support for Kenji is not merely a way of ensuring that her employees continue to receive quality health care, but also a way she too can rise above her current station, by marrying an up-and-coming doctor.

Though this could be said to be the film’s central conflict, it ends up occupying refreshingly little screen time, as Mizoguchi allows the emotions to simmer under the surface, coming a boil only once before being rather satisfactorily settled. What he does in the meantime is really embed the audience in the seediness, the desperation, and the inevitability of the profession, as even those most opposed to it end up finding it their only way out of several horrible situations. After a geisha falls ill, her sister comes to look after her, and comes to practically beg Yukiko for a position at the house, a request Yukiko is forced to dismiss until she comes to understand how dependent that very dismissiveness has been on the success of that very venture. After all, it’s not some lottery winnings or a hidden family fortune sending her to college, but, as the women themselves note, the hard work and immense sacrifices of others.

And that, beyond the (still quite compelling) melodramatic main plot, is the real crux of the film – the way each of the characters comes to see the world from a slightly different viewpoint, and in so doing discovers not only something about themselves (the resolution of Yukiko’s storyline is a rather stunning evocation of bittersweet) but about the world around them and those they profess to love the most. It may not be Mizoguchi’s most ambitious or even audacious film, but it contains all of the aforementioned unrelenting rigor with a very lived-in humanist perspective, making it, quietly, one of his greatest films.

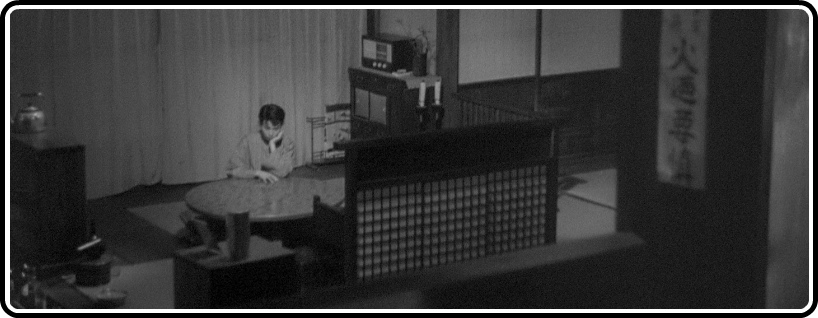

Each of these four films boasts a high definition transfer, and a sort of uniform presentation. Lesser-screened films, especially Oyu-sama, look considerably better, while the wildly popular Ugetsu exhibits a good deal of wear and tear. Masters of Cinema, thankfully, doesn’t let the conditions of the prints prevent a great transfer, though, so all of them have tremendous contrast and depth, an often stunning amount of detail, and mostly the sort of visual integrity one comes to expect from 35mm, while perhaps never quite fooling the even casually-trained eye. They are digital transfers for a digital world, but are in the upper tier of what one sees in such endeavors, extremely robust and dense. The lighting in Uwasa no Onna is so beautifully crafted, and carefully rendered here, I actually gasped at one early shot. Even given that the films are stacked two to a disc, I didn’t notice a shred of compression artifacts or any real loss of quality (they’re fairly short, which helps, but doesn’t always take care of everything). All the films are presented in their original aspect ratio, 1.37:1.

For such a mammoth box set, special features are relatively sparse, though the Tony Rayns interviews that accompany each film go a long way towards covering the information that would interest most viewers. He doesn’t go into a lot of analysis, offering little more than a casual ranking (“It’s workmanlike, not nearly up there with such and such,” and so on) preferring instead to discuss the films’ histories and their places in Mizoguchi’s life and career. As Rayns notes, Mizoguchi was working under an intensely demanding studio system, often churning out a handful of films each year, and by this point in his career had become frustrated with the demands even as his reputation in Japan and abroad had grown considerably in the early 1950s, so he wasn’t always as invested in each film, even those we see here. While Rayns and I may disagree on the relative effects of that disengagement (he sees Chikamatsu Monogatari as somewhat workmanlike), the context he provides is invaluable.

And finally, roughly half of the gigantic 344-page accompanying book is dedicated to these films. Keiko I. McDonald provides the bulk of the work here, with essays on Oyu-sama, Ugetsu, and Uwasa no Onna, while Mark La Fanu provides the overview of Chikamatsu Monogatari. Masters of Cinema also includes the source texts that were adapted to make Ugetsu and Chikamatsu. As is usual for them, it’s a hell of a lot of worthwhile material, and one of those things that really benefits from being owned and read over a long period of time.