I previously wrote about this film for our On the Hulu Channel series. Looking back on it, I was pretty pleased with how it turned out, and found that my perspective on the film hadn’t much changed. It is presented again here, with minor revisions, and new notes on the new Blu-ray transfer.

Man, and you thought the French were ahead of the curveball in depicting 1960s youth culture. That Cruel Story of Youth should exist seems almost second-nature, so forcefully does it emerge from an untapped sense of dissatisfaction and sexual awakening; that it came out in 1960 seems otherworldly. It’s so raw, it’s almost primal. It’s so explicit, it need not show that which it explicates. And as introductions to Nagisa Oshima go, you could hardly ask for better (it was mine, and it being his debut feature makes it doubly fitting).

The film is informally structured around a series of of violent sexual encounters. We meet Makoto (Miyuki Kuwano) as she’s hitching for a ride home with one of her friends. An older man picks them up, and after dropping the friend off, attempts to lure Makoto to a hotel. When that fails, he tries to rape her. He’s interrupted by a stranger passing by, who violently assaults him and attempts to take him to the police, until the would-be rapist offers up some money and is sent packing. That Makoto’s association with Kiyoshi (Yasuke Kawazu), her young rescuer, should end there seems obvious, yet their almost assumed meeting the next day, and the ensuing events, belies one of the film’s many themes – society bills women for merely existing. Because she was in a car with a stranger who offered to help, sex was expected. Because she was rescued, she goes out with her rescuer. Because she goes a date, she then is actually raped. And things don’t get a whole lot less cruel from there.

Beyond the duck-and-dodge method in which Makoto and Kiyoshi fall in “love,” their inseparability becomes almost reflexive. Neither seems to really like the other, but they can’t walk away (ah, young love), especially once their extracurricular activities turn criminal. Using their initial meeting as a template, they extort sexual predators whenever they want a night on the town, but Oshima’s presentation of these escapades is deft, rather than exploitative. He shows only a couple key encounters, each time focusing on Makoto’s evolving response to them. Her habit of riding in cars with strange men is repeatedly turned on its head, reversed, and tumbled until it’s hard to conceive of how this could have ever been a good idea. And yet we’re told right at the beginning of the film that we’re not even seeing her first such ride – was she fortunate before, or is all of this much more familiar than she’s letting on?

Certainly her resistance to Kiyoshi’s aggressive pursuit seems genuine, and as much as the film could be accused of misogyny (this is, on the surface, a story of a girl who falls in love with her rapist), it’s important to note where Oshima points his camera, almost always to the most emotionally vulnerable person in the scene. Usually that’s Makoto, but when the tables turn, his framing underscores these developments. For such often-outlandish subject matter, Oshima’s direction is purely classical, and so richly assured for a feature debut by a man in his twenties.

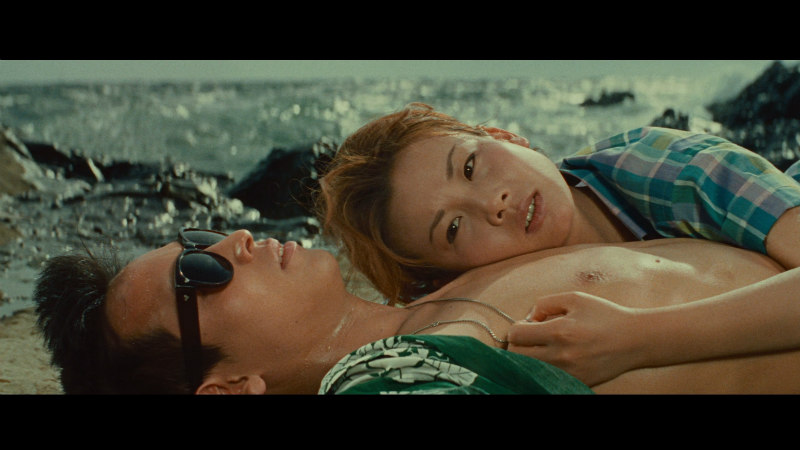

I thought positively of the HD version on Criterion’s Hulu channel, but MoC’s leaves it in the dust, offering much more depth, detail, and warmth. Doing a comparison now, the Hulu version seems washed out and saturated, while the MoC Blu is darker without using the darker palette to cover up compression issues. The colors are bold, as they should be – the tone is primarily primary – but still retain the sort of organic quality of film, never exploding into a purely plastic feel. These elements are more than just pleasing to the eye, though they are that. Oshima’s aesthetic approach is so precise in showing the warmth and excitement that Makoto almost possesses, the vibrance of life around her that remains slightly outside of her. Grain is evenly-distributed and nicely textured. I didn’t notice any significant damage. (screencaps courtesy of DVD Beaver)

On the supplemental side, we’ve an excellent hourlong video discussion with Tony Rayns, one of the go-to guys in the west for all things Japanese cinema, who provides an excellent overview of Oshima’s career, the film’s production history, and subsequent impact and influence. There’s also a 36-page booklet with an essay and interviews. For those looking for an entryway into Oshima and a key point in the evolution of Japanese cinema, Masters of Cinema’s new edition of Cruel Story of Youth is a great way to go.