Cinema’s disconnect from the mainstream culture isn’t precisely anything against the quality of the movies. Relatively speaking, when I look over the list of 109 films from this year I’ve seen, in many ways, the movies are as good as they’ve ever been. What they rarely are, however, is particularly relevant, able to speak to a contemporary audience on that audience’s terms while still retaining an individual artistic identity. It’s well and good to say audiences miss the boat here and there, but how often, really, is there a movie for them to check out that is speaking the language of our times? One that’s set in the present, addresses their concerns without lecturing about it, and tells a truly involving story in a compelling way?

Which is why Olivier Assayas’s Personal Shopper is a breath of fresh air, and damn near a miracle. Here is a thriller, a ghost story, an exploration of grief, a portrait of consumerism, and a thoughtful consideration of the role of technology in our lives that isn’t explicitly about “how we live now”, but is so embedded in exactly that. Moreover, it is lead by a star and significant modern actress in Kristen Stewart, giving to my mind the best performance of her career to date. She plays Maureen (okay, Assayas might not be precisely attuned to “how we’re named now”), a young woman who makes her way selecting clothes for an undefined celebrity, Kyra (Nora von Waldstätten). She loves the clothes, but hates the work, and insists to her far-flung boyfriend or whoever asks that she’s really just there to commune with the spirit of her recently-deceased brother. Because she’s also a medium, you see.

Assayas and Stewart have both spoken in the press about how little they discussed Maureen as a character before production, both seemingly confident in their ability to find her together through the process of making the film. She is thus full of the sort of tics that have turned some off from Stewart – the lip-biting, the stumbling speech patterns, the awkward gestures – but which have made her a contemporary Brando for the rest of us. She has the rare ability to appear iconic despite never posing for the camera. The simplest images of her walking along a river in sunglasses and a sweater, driving through Paris on her scooter, or stumbling about her employer’s apartment in her employer’s borrowed clothes have a way of latching into one’s memory and imagination. Her behaviors embolden this quality of hers by undercutting it. She’s constantly in motion, and thus can never be seen as indulging the camera, or herself within it. She fills her every interaction with tension, her inner confidence not always emerging through how she presents herself. And it’s carefully modulated – with her boyfriend or boutique employees, she takes charge easily. In Kyra’s world, she flounders.

As Maureen gets closer to making contact with her brother (the film makes no bones about it – there are ghosts about), she starts receiving mysterious text messages inquiring about her activities, feelings, and beliefs. Assayas, recognizing how potentially boring that sounds, establishes the bulk of this section within a trip Maureen takes to London for a special set of clothes. She’s constantly on the move, while receiving a series of messages that seem to be following her the whole time. It’s a thrilling sequence, one that heightens the embedded awkwardness of the form (full disclosure – even as a “millennial”, I much prefer a phone call) and also underlines how odd it is that modern communication revolves around talking to people you can’t see or hear, but who are a constant potential presence. Sort of like a ghost, perhaps? It’s a question Maureen is quick to ask on the audience’s behalf.

The answer proves, to my reading of the film, less definite than it initially appears. Assayas directs the entire supporting cast in a very unusual way, their line readings far from naturalistic, with just a hint of a friendlier version of that “Overlook Hotel feeling.” They all seem a little more confident, a lot calmer, a little more inquisitive than not only Maureen, but than most people you and I meet day to day. Assayas doesn’t push the style, and one hesitates in saying Maureen is living in a world of ghosts (or perhaps dead herself), but the out-of-place feeling works so well with so many emotional and thematic tones within the film that it can’t merely be an accidental side effect of a French filmmaker making a mostly-English-language film.

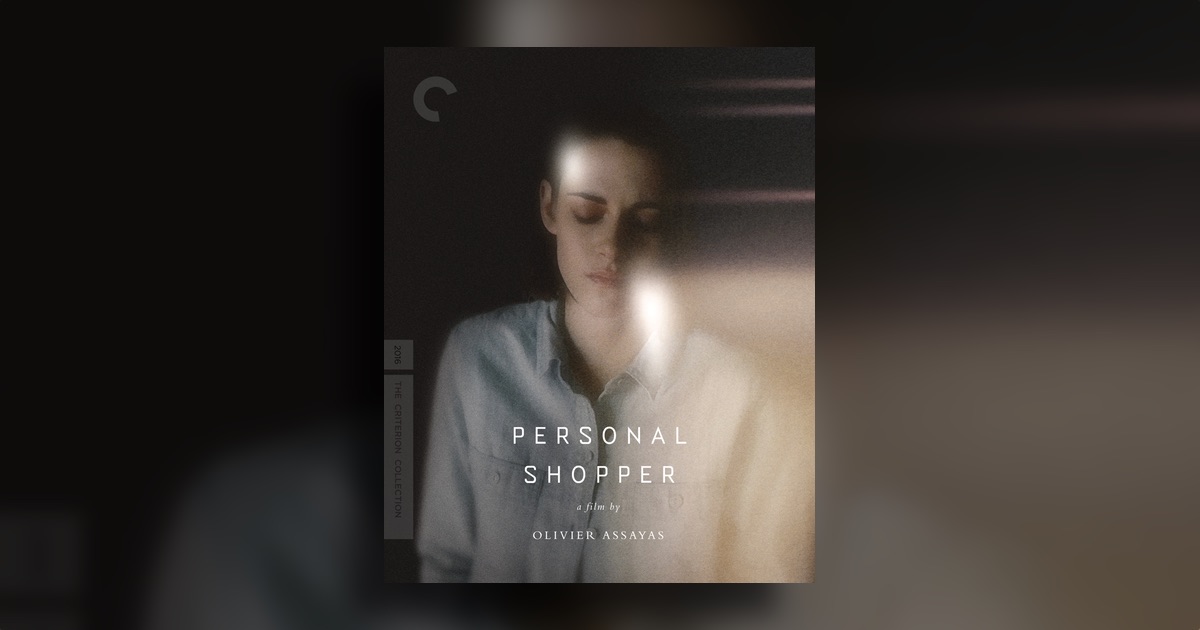

I have to admit, I’m a little torn about Personal Shopper’s inclusion in The Criterion Collection. On the one hand, the year’s coolest film deserves the coolest label and best presentation, and Criterion does expectedly excellent work with it. On the other, I’m desperate to recommend this film to my non-cinephile friends, but the expectation in 2017 that the average moviegoer is going to blind-buy an at-least-$20 disc is a little absurd. So too is its lack of availability on VOD – you can buy it for $13 on most services, or rent it for $5 on the rarely-used Vudu. As this was a title Criterion is releasing through their deal with IFC Films, one could blame either party, but a glance at other IFC releases from earlier this year finds them available to rent cheaply on a variety of platforms. Criterion’s innocence here seems suspect. Keeping a film so contemporary to our times in the least-contemporary platform is a frustrating irony.

Nevertheless. If you are reading this site, the idea of just going out and buying some random discs for more than the cost a decent restaurant meal is far from absurd, and Criterion is here to please. Their release features beautiful cover art, a very stellar transfer, an insightful 16-minute interview with Assayas, and an interesting if characteristically-meandering press conference from the film’s premiere at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival. Best, to my mind, is the essay by Glenn Kenny included in the leaflet, which details the film’s qualities in the expert fashion we have come to appreciate from him.

Personal Shopper is one of the year’s very very best films, and almost certainly a modern classic. I wish it was more accessible to a younger audience that could appreciate it (I think back to the baffled, older matinee audience with whom I saw it back in March), but Criterion have done, as always, a fine job in presenting it, and the label should also be filled with masterpieces of all eras.

![Personal Shopper [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41tNY80m4vL._SS520_.jpg)

![Clouds of Sils Maria (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41xBGcICf4L._SS520_.jpg)

![Carlos (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Ii2AxScYL._SS520_.jpg)

![Summer Hours (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Ainmqyv1L._SS520_.jpg)