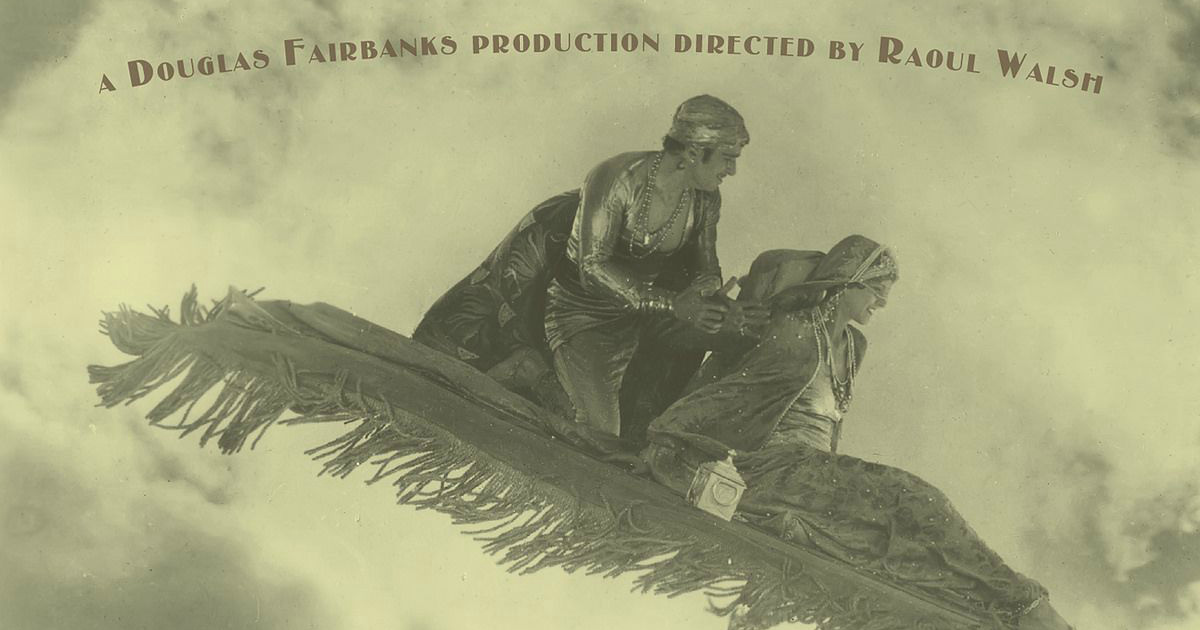

Our standard titling system is a bit misleading in this case. Yes, Raoul Walsh, by all accounts, was on set performing the basic duties of director for 1924’s The Thief of Bagdad. But, according to Fairbanks biographer Jeffrey Vance, and indeed the only credit in the entire film, this is Douglas Fairbanks’s The Thief of Bagdad, from top to bottom. He originated the project. He made the major creative decisions. If Walsh had input into how the film was executed, it had to be approved by Fairbanks first. The auteur system has been faulted for favoring the director, but there’s usually somebody calling the shots.

For this film, adapted from the famous One Thousand and One Nights tale about a common thief who impersonates a prince to win (first the body, then the heart) of a princess, that somebody is Fairbanks.

The resulting film suffers not from lack of ambition, but from too much ego. There’s nothing wrong with Fairbanks favoring so much of the screen time for himself. He is far and away the most compelling player in the talented cast. He relishes each moment he gets onscreen with a joy that might be self-serving, but which also draws the audience in and asks them to share in it. The problem is his eagerness to show how much work it all is. Like the overlong blockbusters of today, the dramatic aspects are both overwrought and undercooked, the spectacle comes a little too late, and the poetry of cinema suffers in an effort to make sure we see the special effects for as long as possible.

Not that the effects aren’t extraordinary, and often invisibly-accomplished even today. But to reduce the camera to merely a witness for these contraptions reduces their potency. Nearly every shot in the film is locked-down, stationary; even a pan seems too audacious for Walsh and Fairbanks. The film is not bereft of a certain entertainment value, but in some ways, it’s too little, too late. By the time Fairbanks embarks on the fantastical parts of his journey, we’re over 90 minutes into a 150-minute movie. The set and costume design has certainly been remarkable to this point, but, as viewers of modern Tim Burton movies know, these alone do not make for a compelling film. Even if you do have an engaged, exciting protagonist.

With a 2k transfer more or less ported over from the Cohen Media Group’s Blu-ray from last year (DVD Beaver notes tweaks to tints and a higher bitrate), Masters of Cinema presents the film on a Region B locked Blu-ray. The transfer is somewhat problematic from the get-go. Though they’ve done a marvelous job cleaning up the film – there’s shockingly little damage for a film of its age, perhaps due in part to Fairbanks’s forward-thinking ideas of film preservation – and the tinted colors look magnificent, clarity and depth suffer tremendously. I’m not saying the film should look as sharp as Guardians of the Galaxy; it just doesn’t look as sharp as any other silent film Masters of Cinema has released. And when that sharpness suffers, so too does depth, which in turn doesn’t allow us to really see the true accomplishment in the production design.

This could be due to a few factors. The first is that this was the best they could get out of the available elements. However, due to how immaculately the film seems to have been preserved, I wouldn’t bet on it. The likelier scenario is that at some point along the way – either in restoring the film or the actual making of it back in 1924 – it was decided that a softer focus would hide a lot of the contraptions behind the visual effects. Some wires remain visible, but as I said, for the most part, I was really impressed by how seamless many of the effects were. With a sharper focus, it’s very likely the seams would start to emerge. The soft focus does lend a sort of dreamlike quality to this fable, but because I’m not sure about the motivation behind it, I have a hard time recommending it as enthusiastically as I typically do.

Carl Davis provides the excellent orchestral score, available in both stereo and 5.1.

Two special features are available on the disc. The first is a 17-minute video essay called “Fairbanks and Fantasy” that has a lot of good information to impart regarding the production and release of the film, but its presentation – a slideshow-esque format of stills from the film and explanatory text – is so flat that it’s really a chore to watch. Much better is the commentary track by Fairbanks biographer Jeffrey Vance, who has more than enough information to fill the film’s epic running time. He’s a little disorganized, providing a sort of summing-up statement halfway through the film and occasionally surprising himself when something he’s saying happens to line up with what’s happening onscreen, but his enthusiasm for the subject and wealth of knowledge make it a great listen for fans of the film, the actor, or silent film in general. Both of these are also available on the Cohen disc.

On the booklet side, we get a pretty good essay by Laura Boyes of the North Carolina Museum of Art, which essentially offers a series of short biographies of the people who worked on the film, and a couple tidbits from the production. Like Vance, she’s more focused on facts than emotional or critical engagement, and so there’s some overlap, but it’s short enough to make for a nice companion piece.

If The Thief of Bagdad is one of your favorites, chances are you already own the Cohen edition, but, in the event you don’t, MoC’s additional essay (and better cover art) give this a slight edge, though in many respects the discs are identical to one another. It wasn’t exactly my cup of tea, but it’s a towering achievement and a landmark silent film, and I’m pleased to see it fly onto Blu-ray.