The action moves in slow motion as an overwhelming, droning hum permeates the soundtrack. The frame is double-exposed – some sort of bright light further punishes our senses. People are running through a police station, toward a room littered with evidence of chaos. As we peer in the door, one man stands aggressively at the far corner. The camera quickly looks away, but not so much so that we can’t recognize Sean Connery.

For a production he initiated, Sean Connery gets one of the weirdest introductions I’ve ever seen granted a major star. But then, this is hardly the sort of role you expect a man coming off a decade of success as James Bond to push through the system. Even his creepy presence in Marnie isn’t nearly the subversion he pulls off here. Sidney Lumet’s The Offence, adapted from a stage play by John Hopkins, is a tough, severely off-putting character piece about a police detective who has witnessed too many horrors to remain moral any longer. The question horrifies him as much as it does the audience – just what is he capable of?

From the burst of violence that opened the film, we move into a flashback. Children are going missing in a small English town. They’ve gotten lucky with the last one – she was found alive. Though she offers little in the way of help, they round up a suspect. Detective Johnson (Connery) is convinced they have their man, that every second they waste is another second he could be punished. He has no evidence. He’s the sort of man who will trust his gut more than anything every time. So he sets about punishing the man himself. We only see glimpses; perhaps there was a provocation? The man is carted off to the hospital before even Johnson can make sense of what happened.

He goes home to his wife, whom he loathes, but his every word against her is in response to some aspect of himself he cannot stand to face. He resents her inability to fully come to terms with the terrible things he’s seen on the job, but he’s clearly not dealing with them much better. He’s called back to the station and questioned by a superior officer trying to figure out what happened between Johnson and the suspect. Finally, we flashback to the interrogation room – the third time we’ve been there, only this time we get nearly the whole scene. Enough to see what really happened, anyway.

The final scene, like so much of the film, is a mix of clearly-delineated actions and sudden leaps that are almost nightmarishly inexplicable. This tension is established early on, when Johnson finds the latest missing girl. Asleep in the woods, her clothes are tattered. When he wakes her, she’s terribly frightened. He tries to comfort her, but he doesn’t signal to the search party that he has found her. He just keeps looking at her, telling her to be quiet, laying her down in his coat. Every action could be either calming or passively violent. Later, he’ll imagine (remember?) what the girl looked like lying there happily in the sun. He’ll talk of white skin and breasts.

What’s that line about staring into the abyss?

Lumet takes a rather uncharacteristic approach to the editing, leaving the sensation that a few tiny, valuable frames have been snipped out of scenes, that we’re never quite seeing the whole story, or have entered, along with Johnson, a temporary state in which we cannot totally control or account for our actions. He seems constantly to be slipping down a whirlpool towards something he’s already done. The past, present, and imagination coexist, so that the only way to get these truly awful images out of his head is to do something equally awful. Or perhaps his actions won’t seem so bad, comparatively.

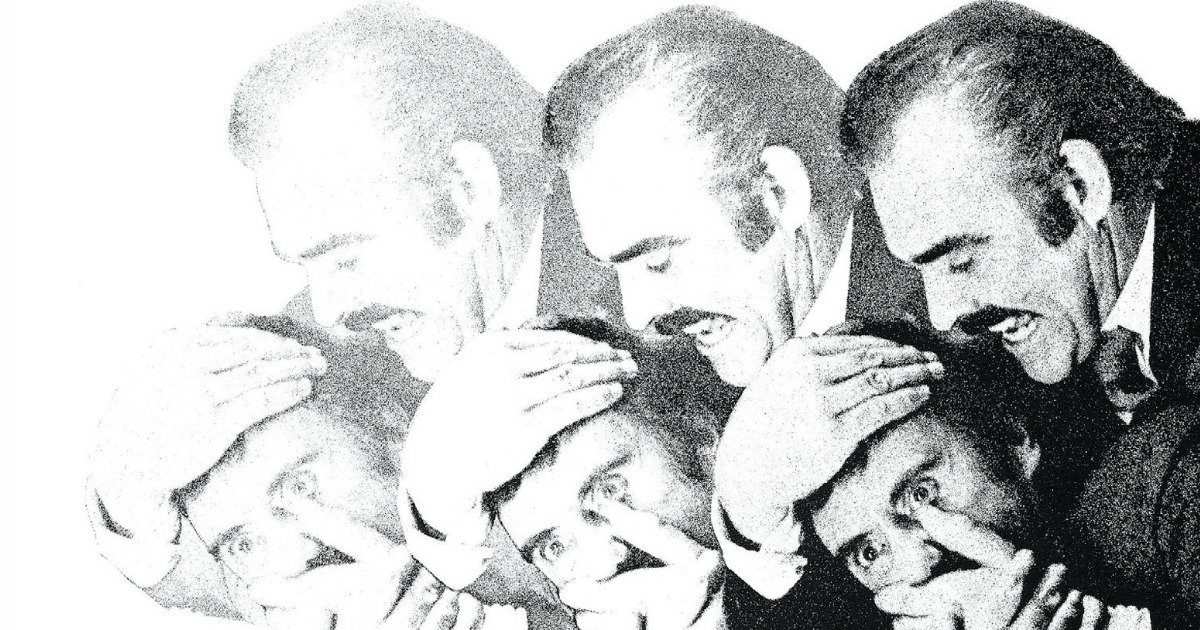

Connery constantly thrusts his hands in front of himself, trying to hold onto some element of himself, or decency, or sanity. Or he’s simply trying to remind himself that he exists, a sort of centering technique. His clenched-teeth, steely-gaze performance is a mirror of the film, at all times barely on the edge of violence. He flips open a closed liquor cabinet like he’s hoping he’ll accidentally destroy the door and never have to deal with the barrier again. Are his punches similarly motivated?

If Lumet’s cuts bring Johnson closer to his psyche, his frames bring everyone closer to the fate. Just before the suspect is picked up, he stumbles drunkenly towards the path of a police car, both destined to arrive at the same point. As Johnson’s wife watches him vanish to be questioned, she’s isolated on the patio of her high-rise apartment, the only one awake in the middle of the night, the only one looking out on the world. Even that first shot of Johnson says it all about his limited capacity – he conquered that room, but the bustling activity outside will overpower him.

The film doesn’t assign guilt, to either Johnson or the suspect. Simplistically, it could be considered a look at how the police and the criminals they catch are simply two sides of the same coin. More complexly, it considers how we’re all corruptible, or already corrupted. It’s not that morality doesn’t exist; but perhaps a moral person does not. There are only those who know the worst of the world, and those who shut themselves away in the bathroom, vomiting up what they’ve just heard.

Masters of Cinema brings The Offence to (Region B locked) Blu-ray in the U.K. via, reportedly, a slightly tweaked version of the same master Kino utilized for their U.S. release last year. It has some traits common to modern transfers – high contrast and a general blue/green tint especially, but both seem suited to the film itself, and could be inherent qualities. Whatever the case, I was quite pleased with the quality. I’ve read elsewhere that it doesn’t exhibit enough depth and that the grain is too inconsistent, but these qualities are very common to films made in this era. I found The Offence‘s presentation to be quite good – sharp, strong colors, quite filmic. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio, 1.66:1. (screencaps courtesy of DVD Beaver)

I was even more taken with the supplements MoC put together. Instead of chasing down archival interviews with Lumet or Connery, they brought in brand-new interviews with people on the sidelines. All are fairly short, but have good insights into the role each played in the development and making of this rather modestly-scaled production. Theatre director Christopher Morahan (who first brought Hopkins’ play to the stage and helped develop it into a film), costume designer Evangeline Harrison, assistant art director Chris Burke, and composer Sir Harrison Birtwistle may not seem like they could have exerted much influence on such a small, character-based, contemporary-set film, but once you start looking further into these things, you can’t stop noticing their contributions. They also just have great stories that more high-profile talent would perhaps be more reluctant to share.

The accompanying booklet features a great new essay by Mike Sutton – his writing just as compelling as the film itself – and an interview with Lumet from 1973, which, though it touches on The Offence, is mostly about his general process and approach to cinema at the time, when he was making at least one film every year. Very good stuff.

In an era defined by “gritty realism” and lurid material, The Offence is one of the most unpleasant, seedy mainstream films I’ve yet seen. Beautifully told by Lumet and Hopkins, commandingly performed by Connery, this was a real revelation of talent from people for whom I already had quite a lot of respect. Masters of Cinema did a wonderful job putting this package together, and it’s an easy one to recommend.