“They don’t look very happy.”

“Why should they? They just got married.”

So begins Stanley Donen’s 1967 film, Two for the Road. Many similar sentiments will be shared by Mark (Albert Finney) and Joanna (Audrey Hepburn) throughout the film, which bounces in and out of various trips they take through France. We see them as young people in love, as newlyweds, with another couple, as new parents, as embittered and sick of one another, and so on. After the first few trips through time, Donen (working from a screenplay by Frederic Raphael) doesn’t explicitly state where we are at any moment. Hepburn’s hair is the only definite signpost we get, and that only gets you so far. Yet for all their talk of the misery that accompanies the responsibilities one accumulates after many years of living together, Two for the Road is not a miserablist portrait of marriage. It’s a compassionate one.

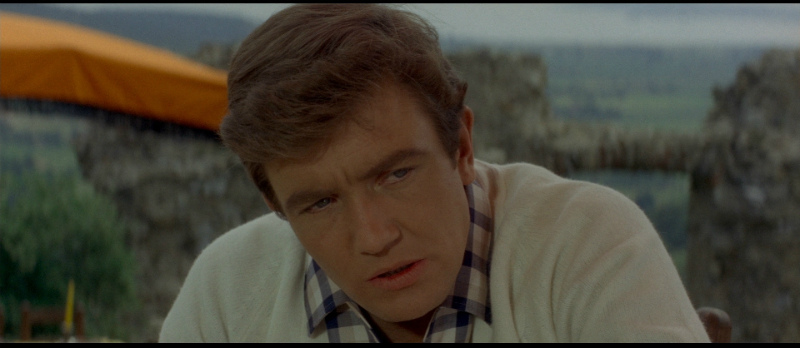

Like many young men, Mark never wanted to get married. He certainly didn’t want children. The right woman has a way of changing one’s mind. Their initial trips together are indeed idyllic, but such experiences can’t be repeated. Sleeping in a cement cylinder, changing your plans at the last minute, or abandoning a trip altogether all work out swell when you haven’t anywhere else to be. But success breeds commitments, and commitments restrict the sort of lively, unrestrained adventures that brought Joanna and Mark together in the first place, he laying on the back of a tractor as she sits in a wrecked bus on the side of the road.

Donen came up through musicals, making his directorial debut (alongside Gene Kelly) with On the Town. They arguably perfected the form with Singin’ in the Rain, but by 1955, only six years after their debut, they parted ways with the melancholic It’s Always Fair Weather. But he still had musicals to make – his next film was Funny Face, starring none other than Audrey Hepburn. They re-teamed for Charade in 1963, and concluded their partnership with Two for the Road. Each time he brought out something new in her, developing and challenging her screen persona. In Funny Face, she’s a young intellectual yearning for Parisian culture. In Charade, she’s lived in Paris for many years; first single, then with her husband, whom she’s about to divorce. In Two for the Road, she’s vacationed throughout France so many times, she’s as sick of it as she is her husband. The holidays she once yearned for and grasped excitedly have grown tiresome and familiar, as routine as her everyday life.

Like many stars, Hepburn didn’t always choose the best projects, though she was reportedly very selective, stringing directors along for months at a time as she considered a part. Indeed, as Donen says in the commentary track accompanying this release, she initially turned down this film when he explained the concept to her. Once she read the final script, she couldn’t resist; who could? It’s undeniably modern, fresh, and imaginative in the creative space of the 1960s American cinema. It’s more in line with the European pictures of the time, and just as vital to the oncoming New Hollywood wave as more overt, but less resonant films like Bonnie and Clyde or The Graduate (both also released in 1967). Yet it doesn’t rely on that “European flavor” to coast on mood and charm. It’s really damn sharp, each transition feeling like a natural part of the narrative; devices that could be merely clever (Joanna diving into a bed cuts to Joanna diving into a swimming pool; she claps her hands in one era, and a waiter appears in another) become the very essence of the film. These vacations have become repetitive, more often reminding Joanna and Mark of wonderful moments than creating new ones.

The film is introduced in what might be considered “the present moment;” it is certainly the latest era they will explore. But the time-hopping drama, though initiated as a sort of memory (in voiceover, we hear phrases like “I’ll never forget when…” or “surely we were happy when…” as we journey to the past), function more within the spectrum of the film the way Claude Rich’s more literal time-travel does in Alain Resnais’ Je t’aime, je t’aime, released the following year. The past, present, and potential future are constantly in flux, informing and adjusting perceptions of the other. Our present circumstances and feelings change the way we perceive the past, and our past certainties inform our present; all threaten to change our future.

Two for the Road isn’t a musical, but shares with Donen’s earlier works a sense of the musical. The freewheeling scenes play lyrically, at once mournful and joyous, as any look back at the development of an unhappy marriage must be. Shot entirely on location, Donen uses his environments in a manner not dissimilar from his studio sets. It’s worth remembering that this is the same filmmaker whose On the Town was the first major studio musical to shoot on location (not entirely, though he pushed for it). He uses the environment to express character and theme, showing reflections of the countryside pass by in front of his stars’ faces, obscuring their immediate emotion as the world passes them by. Even their hotels match their feelings – small, intimate inns in the early days, too-expensive resorts in the newlywed years, and cramped, industrial quarters once their daughter comes along.

Perspective is everything; but whose? The inherent danger of two men collaborating on the story of a heterosexual marriage is that it will emerge too male-centric. Two for the Road largely avoids this; Mark is the more volatile one (and Albert Finney relishes every outburst, letting it embolden and contrast with the image of the mid-century masculine ideal), and his tendency to explode at the slightest indignation will inevitably make him seem the worse of the two. But Joanna’s (immediately apparent) habit – to patch over conflicts between them and withhold whatever grudges she may carry – can be just as damaging. When he has an affair, it’s a fling; when she has hers, it’s all-consuming. Two for the Road doesn’t prize one approach or damn the other, but fairly represents how outward calmness can mask bitterness.

Donen’s road isn’t a closed one, leaving much open-ended, not the least of which is the film’s ending. We’re back in the most recent era, with Mark and Joanna off to another adventure, coming off an extremely bitter dialogue, but seemingly on the upswing. “Bitch,” he says, as she plays a familiar joke on him. “Bastard,” she replies. They both smile, and kiss. I myself favor the playfully combative in a relationship, so I took it as a net positive for them. They had just come from a party, at which Mark finds out he landed a new job. When he tells Joanna, she’s enthusiastic. “Good!” she exclaims, then looks more questionably at Mark’s expression, trying to read it. “Good?” she ventures. He shrugs, and they continue dancing. Shortly after, they escape together from a conversation with their host that neither wanted, but he felt indebted to have. Perhaps they’ve come to a sort of contented understanding of one another, and with what they can reasonably expect from life.

Masters of Cinema is the very first company worldwide to present Two for the Road on Blu-ray, and they’ve done a remarkable job with it. The transfer is gorgeous. Sharp, but not overly so, still carrying a bit of the softness one would find in a color print from this era. The colors are captivating, but far from oversaturated; grain is beautifully subdued, lending a hint of texture and detail. I didn’t notice any damage whatsoever, nor any overt or intrusive digital enhancement. It looks like viewing a film print without the need of a projector. (This is a Region B locked disc)

The film is supplemented with a great commentary track by Donen, recorded in 2005 for the DVD release, and an archival interview with Raphael from, I believe, French television. Donen’s commentary has its share of gaps, but honestly, this is such a full, rich, consistently entertaining film that I never minded, and when he does chime in, he offers tremendous insights into the production and how he managed to work around existing environments to achieve his vision. Sometimes this meant building onto restaurants (at least one kept a platform he built) or carting around duplicate cars or strapping a camera to the hood of one of them with no idea what the finished product would look like. Even though he’d been a filmmaker for nearly twenty years when he made Two for the Road, Donen was still in the prime of his life, and seemingly willing to break any and all rules presented before him. The interview with Raphael is a nice addition, too, showing things from the writer’s perspective, and getting into the way he structured (mostly at random, it seems) this unusual film. The booklet includes an analytical essay by Jessica Felrice, heavy on semiotics.

The more I see and think about it, the more Two for the Road just seems like, flat out, one of the greatest films ever made, from a director and star who grow in my esteem more and more each year. What they do may look breezy or “light,” but the construction and execution is so carefully considered and so exacting that it’s little wonder so few other films compare. The trio they made together – Funny Face, Charade, and Two for the Road – do what they do better than just about anybody ever did. Two for the Road may be the best of them, capturing the moment when someone looks into your eyes and sees everything you’ve ever dreamed, and eventually what happens when you’re left searching for that look again.