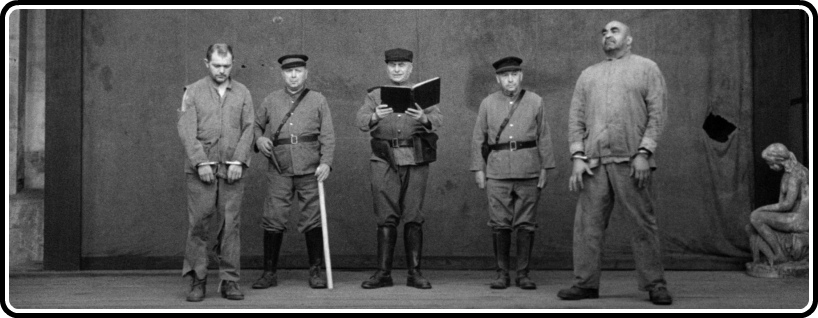

A general guideline for setting up a surrealist portrait of a dictatorship government is to make it as silly as possible; the more outlandish, the better. And Borowczyk’s set-up for his live-action feature debut, Goto, Isle of Love, is quite silly indeed – an earthquake eighty years prior has cut the titular island off from the larger civilization, so they have simply maintained the society they had then, regardless of how inane that structure is. For example, every crime carries the death sentence, but this is carried out by simply having two condemned men, regardless of their crime, fight each other. Whoever wins is pardoned; whoever loses is dead. We meet the film’s protagonist, Grozo (Guy Saint-Jean) after he’s convicted of stealing binoculars, and is forced to fight a gigantic man who has recently, for his sixteenth crime, murdered a corporal.

But what’s somewhat refreshing, and all the more odd, is that that same protagonist is far from an innocent. This man is certainly wronged by the system, but that does not make him a hero. He wrangles his way out of the fight by appealing to the generosity of the dictator’s wife, Glossia (Ligia Branice, whom we previously saw in Borowczyk’s short Rosalie), in a moment of such intimacy that he constantly returns to it in the course of his rather complex and conniving scheme to win her heart, or at the very least eliminate others who might.

Not that the dictator, Goto III (Pierre Brasseur), is much competition. His authority has become so assumed that he’s simply bemused by the ins and outs of ruling over the island’s petty citizens. His wife’s love is beyond question, as with everything else in his life, which makes it terribly easy for her to fool around with her riding instructor (Jean-Pierre Andréani).

Even before I found out what story we are to follow, or even the world we were to explore, the set design immediately leapt out. I am not at all surprised to learn that Borowczyk took a very hands-on approach to this aspect, often stealing away supplies and repainting the sets, or creating the props (most notably an ingenious fly catcher), himself. Borowczyk anticipated the postmodern reverence for the past, especially in repurposing objects of the past for modern purposes, crafting a world at once intimidating, foreboding, and kind of awesome. The simplicity of the world is at once its appeal – it seems rather easy to operate within it, and it’s incredible to see how much Borowczyk constructs from relatively little – and its terror. Every object seems crafted for utility; is our purpose only to operate this world?

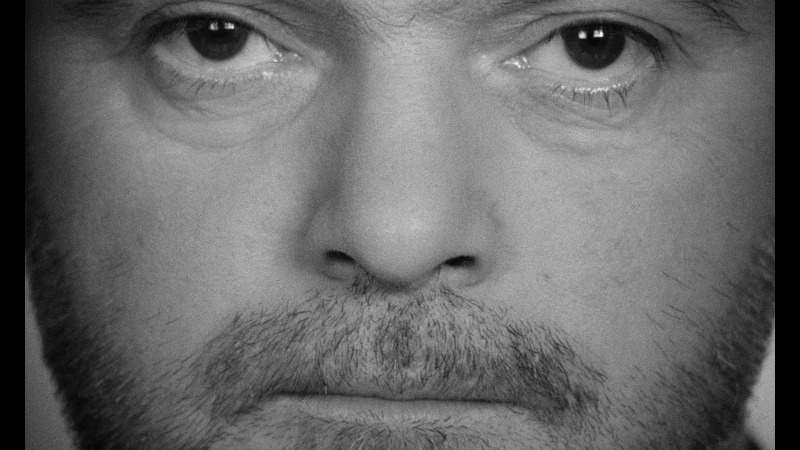

Borowczyk films the proceedings with something of the same remove that informed his shorts. It is suggested in a documentary accompanying this release that he treated his actors much like his drawings, only asking of them specific movements and blocking, while offering little in the way of performative or emotional direction. This comes across a bit in the film, but the performances are so sharp and lively that his collaborators must be underselling him a bit, or he just had tremendous fortune in the casting process alone. Saint-Jean has this tremendous face (that Borowczyk even utilizes in extreme close-up), at once endlessly scheming and totally innocent; it is immediately clear that the limits of his ambitions will make his efforts either hilariously ineffective or catastrophically dangerous, as he cannot see beyond his own needs.

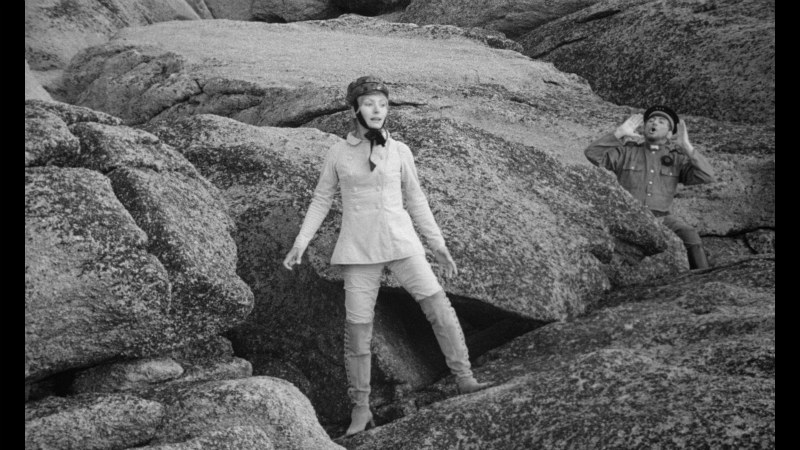

Brasseur is the kindest force of nature ever unleashed, while Branice, an almost impossibly beautiful woman, spends most of the film helmeted, in accordance with her riding lessons. Even natural beauty is corrupted in this world of utility.

Goto, Isle of Love was restored thanks to a Kickstarter fundraiser. While I don’t have any skin in the game, so to speak, I have to imagine those who did will find that their efforts paid off handsomely in Arrow Film’s new (Region B locked) Blu-ray. The video embedded below gives you a pretty good sense of how much work was required, but even without knowing the extent of it (as I did not when I saw the film), this is a stupendous black-and-white transfer, rich in detail and contrast without turning it too stark – the grayness of the film is essential in communicating the decaying nature of the world, and that is much more prominent than strong blacks or whites. Grain is thick and textured, and depth is exceptional. There are a few color inserts that aren’t quite as commanding, but my guess is that has more to due with the limits of the color film stock of the time than the restoration efforts. The film is presented in glorious 1.66:1.

Artist Craigie Horsfield provides a really good introduction to the film, offering personal remembrances as well as a sort of scholarly analysis. It does run a solid eight minutes, though, and goes into a bit of detail on the film, with Arrow inserting some clips, so, as with most introductions, is probably best viewed after seeing the picture. “The Concentration Universe” is the aforementioned documentary, running twenty-one minutes, on the film’s making, including interviews with Andréani, assistant cameraman Noël Véry, and camera operator Jean-Pierre Platel, all of whom have quite different, yet complementary, perspectives on the man, his working methods, and the results thereof. Lastly, we get a thirteen-minute piece with the curator of a museum that houses Borowczyk’s “sound sculptures,” a series of wooden contraptions meant to be toyed with in a certain way to produce certain unusual noises. It’s a fascinating look into Borowczyk’s career outside of cinema.

Top all that off with a booklet containing essays by Daniel Bird, a contemporary review by Cahiers du cinema critic Patrice Leconte, and a Sight & Sound profile from 1969 by Philip Strick, which proved to be a major introduction to the filmmaker for English-speaking audiences.

All in all, a worthwhile package for a fascinating film. I’d still recommend those new to the filmmaker start with the shorts release, but for viewers less inclined towards animation, this is a tremendously accomplished, fascinating picture all on its own. Especially if you dug Criterion’s Pearls of the Czech New Wave Eclipse set, Goto, the Isle of Love is definitely for you.