Despite a decade of rarely-paralleled innovation, brilliance, and acclaim, Walerian Borowczyk was not making a great deal of money with his art. By 1972, the short films he churned out only a few years prior no longer enjoyed the sort of exhibition they once did, and his trio of features – Mr. and Mrs. Kabal’s Theatre; Goto, the Isle of Love; and Blanche – had not exactly set the box office on fire, or left investors with a great deal of confidence in whatever he might dream of next. I cannot ascertain whether his reputation as an exacting artist (whose stubbornness lead to month-long production halts) hurt him even further in this realm, but it certainly couldn’t have helped, especially by the time it came to directly (and nearly literally) battling his producer on the set of Blanche. What producer’s going to line up for this guy’s next vision? And who could fault their hesitation?

In swoops Anatole Dauman, supplying Borowczyk with an important opportunity for the second time (he’d previously produced his 1959 short The Astronaut); a series of short films, strung together into a feature, that would feature explicit depictions of sex. After all, if there’s one thing that had proven financially rewarding in the past twenty years of European cinema, it was breasts. And as censorship laws were relaxing, there was a real opportunity to show people more – more! more! – than they’d ever seen before, all under the socially safe designation of “art.”

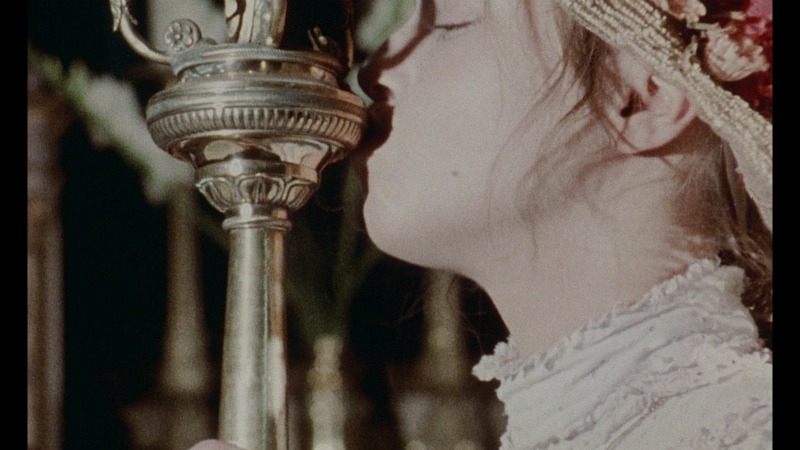

I don’t know Borowczyk’s degree of enthusiasm in undertaking the project, but, aside from a few rather extraordinary sequences, the film has the feel of something not entered into with much at all. As the title indicates, it is composed of four discrete stories, each tackling a different angle of “forbidden” sexuality (fellatio, masturbation, homosexuality, and incest) and, perhaps more importantly towards any attempt to find meaning in all of this, feminine repression (by family, church, and state). In one, a young man lures his younger female cousin to the beach to blow him so that he might climax as the high tide crashes around them (the mechanics of which are hilariously mapped out); in the next, a grounded young girl uses religious materials in masturbation; following that, a countess ensnares young virgins in a plan too sinister and shocking to spoil here (but which, suffice to say, makes for the film’s most haunting passage); finally, a young woman is seduced by the ostentatious decor of the life of religious officials, to such a degree that she willingly participates in a threesome with her brother, a Cardinal, and her father, the Pope.

While I usually scoff at critics’ he-doth-protest-too-much attempts to distance themselves from sexual stimulation via cinematic images by declaring them “not at all ‘sexy,'” I should probably note how extraordinarily, and no doubt purposefully, un-sexy the vast majority of this material is. If one of the requirements for pornography is that its intention is to sexually excite the viewer, then, well, perhaps I’m just a prude, but Borowczyk’s late-career reputation as equal parts pornographer and artist just doesn’t quite fit. Much has to do with ownership. As I noted above, each section explores some way in which women are repressed or exploited by various (and not always male) elements of society. The nudity and sex in much of this film is akin to watching a rape scene; even when the women participate willingly, there is the sense that they have been manipulated – perhaps casually, all their lives – into doing so.

The one exception to this is the second sequence, in which the young girl waits out her punishment by reclaiming religious icons for her own carnal pleasure. While arguably immoral, there is a base satisfaction to be found in an oppressed person taking the instruments of her oppressing and subjugating them to rather lecherous treatment.

Now, arousal need not be the only aim of sexually explicit cinema, but Borowczyk keeps women’s naked bodies onscreen for such extended periods of time that it’s difficult to imagine he didn’t at least have this potential in mind. In the third section, about the countess and her virgins, Borowczyk spends what feels like at least half the time simply watching the girls shower together and run around naked. But because his directorial stance is naturally one of remove, he communicates little of the glee that he seems to expect from his audience, as though the simple presentation of these bodies should be sufficient for our base desires; resultantly, his disinterest became my disinterest. Contrast this film with other explicit contemporaries, like Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life or Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Successive Slidings of Pleasure and Eden and After; there are two filmmakers who, yes, certainly have some prurient interests, but who also are willing to deeply investigate the nature of their own pleasure and desires. Immoral Tales nearly offers contempt for the very act of wanting, while simultaneously offering to modestly satisfy it.

Essentially shot as four totally separate films (by four separate cinematographers), the look and presentation of the film differs slightly from chapter to chapter, but Arrow’s new Blu-ray edition of Immoral Tales looks quite pleasing on the whole. The second chapter, in particular, really stands out, heavy on grain and contrast and somewhat flat in shape, whereas the other three offer variations on the familiar European color palette of the early 1970s – bold, but somewhat faded, warm colors, with somewhat placated blues and greens and such. Damage is minimal. All around, a very healthy, celluloid-esque presentation.

On the special features side, this is one of the more elaborate of Arrow Films’ offerings in their slate of Borowczyk releases. First, they offer two different versions of the film – initially, Borowczyk included a short film called “The Beast,” but he decided instead to expand that into its own feature film (which I will be reviewing). So you can watch a version of the film with that cut in, or simply chapter-skip to the added section (the only chapters on the disc are between those of the film). After that, look to a solid introduction by Daniel Bird (presented as a series of clips and text, rather than an on-camera interview); a 17-minute making-of piece that does a great job of exploring the uncomfortable atmosphere of the early years of loosened censorship; two different cuts of Borowczyk’s short documentary A Private Collection (looking at erotic memorabilia); and an eight-minute video piece capturing a reunion between crew members of various Borowczyk productions. Additionally, a booklet features illuminating essays by Bird and Philip Strick, contemporary reviews, and an essay by Michael Brooke on A Private Collection.

Bird’s and Strick’s essays, while not entirely convincing, did help me understand some of what Borowczyk might have been getting at, and, more importantly, the value the film might hold for someone other than myself. If you are curious about the film, or already love it, Arrow’s presentation, along with the supplements they produced and assembled, are certainly top-notch, and on the basic merit of its production, I can recommend it.