In the rather broad assortment of films that could be called “genre cinema,” there is the pure and the impure. The pure is the genre stripped to its essence – a killer is hunting a girl, a group of people are trapped in a ship on the edge of space, a man tries to cover up a crime he didn’t mean to commit, someone tries to pass under an assumed name in high society. Stock scenarios, simply told. The impure takes those elements, or others familiar to these genres (horror, science fiction, film noir, screwball comedy, etc.) and subverts or perverts or manages to let them all turn a bit screwy to tell some whole other type of story.

The problem with the “pure” genre picture is that it doesn’t appeal much to those who aren’t naturally keen on it. The impure, conversely, will likely turn them off. And that’s fine. Not every film has to be for everybody. Luckily, in Yasuharu Hasebe’s Massacre Gun and Retaliation (sold separately, but with complementary supplements), Arrow Video has found a film to fit each bill.

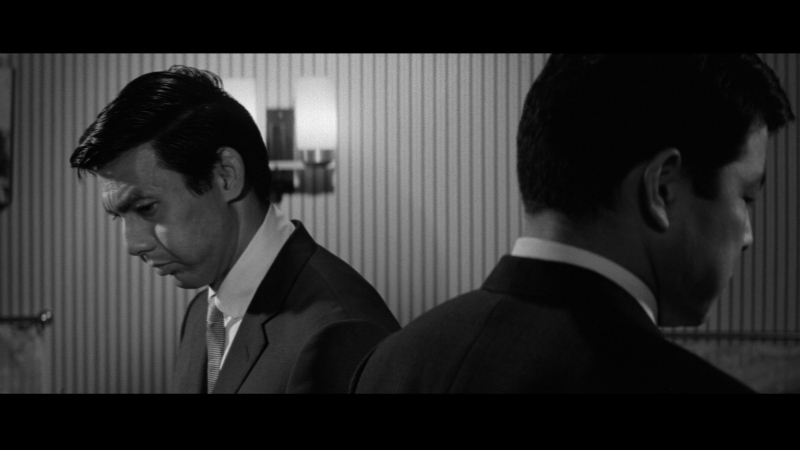

In Massacre Gun (1967), Jô Shishido (Branded to Kill, A Colt is My Passport) stars as an operative for a major gang who, after being ordered to kill the woman he loves, breaks away to form his own crew, initiating a turf war in the process. His brothers are standing alongside him, but will they be enough? Many a shootout will tell. Whereas these sort of films usually focus on the surrogate-father relationship – the gang boss probably rescued the protagonist off the street, brought him up as thought he were is own son – Hasebe looks instead at the fractured relationship between Shishido and another member of the bigger gang. Once close friends and coworkers, they’re forced to battle each other, possibly to the death. Mob films are usually so invested in allegiances that these sort of relationships turn sour the moment one party diverges (maybe the victor will coolly say, “It’s a shame things had to turn out this way”), but Massacre Gun repeatedly reinforces that these guys really do not want this to turn violent. Hasebe finds many a lyrical moment to break up the action, pausing to reflect on the moral and emotional consequences of these (admittedly) exciting fights.

Still, there’s a sort of cool detachment at play, a desire to keep everything looking at least a little desirable. Jazz music haunts the soundtrack, the fights not terribly bloody, and the despair more than a little romanticized. Any subversion of the genre is backgrounded – most notably, the music largely comes (in the context of the film) from a mixed-race piano player, providing a type of character rarely seen in Japanese films of the period. A minor note in a film otherwise full of stock types, but an interesting one nonetheless.

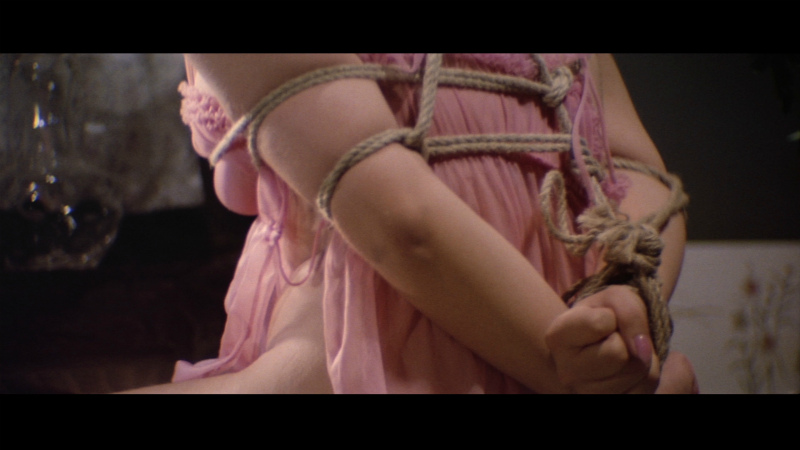

Retaliation (1968), however, is a stunning example of just how malleable genre can be, and how gutting. Certainly there’s the literal version of that – Retaliation is a bloody, bloody film. Never is an act of violence committed without forcing the audience to face the consequences. This approach extends outward, as love interests become rape victims, and business deals both legal and illegal devastate communities. Unlike Massacre Gun, the conflicts are not neatly contained. They are pure forces of destruction. Hasebe does not distinguish between gangs and real estate developers, very pointedly linking the two as essentially criminal enterprises, regardless of how the law may classify. The plot is at once tightly organized and loosely executed – a recently-released convict (Akira Kobayashi) returns to find his former gang in tatters, and takes on a job overseeing a more vast, profitable, but unpredictable enterprise. They liberally exercise their capacity to do anything, to anyone, at any time without consequences, and the onslaught of depravity is not for the faint of heart.

And it’s not simply a matter of the blood and the sex and all other manner of perversion. It’s in the camerawork, mostly handheld, which sometimes struggles (purposefully) to keep up the mayhem. A chase scene lit only by flashlight turns an ordinary pursuit into a descent towards madness. The onscreen vulgarity is matched by these sort of perverse formal choices. Hasebe will frame a shot that keeps some odd object (a plant, a bowl, a couch) in the foreground, obscuring the very action meant to incite. Why? An act of (self-?)censorship? An effort to force the audience to look closely for the carnage they desire? The effect is bracing. It’s as though by making the “wrong” choice, Hasebe has more closely aligned his film with the immortality he depicts.

Of the two releases, too, Retaliation is treated better on every level. The transfer is sharper, more textured, more filmic. Massacre Gun looks like video, to the extent that the image jitters a bit every time there’s a cut – it could be left over from an original splice, but it looks more electronic than that. It’s too “clean” and smooth, the contrast too muddy. It’s not awful, but it’s not particularly commendable. Retaliation looks more natural, perhaps simply due to it being in color in an era when a certain bleached, worn-out look was common, but the grain integrity is definitely more resilient.

The supplements on each release are meant to complement the other. A discussion with Tony Rayns splits the duties between the two discs, offering on Massacre Gun a history of Nikkatsu (Hasebe’s employer, and the production company behind the films), and on Retaliation a more focused discussion on Hasebe and some of the principle players on both films. The latter proves more pertinent, and irreplaceable – while histories of Nikkatsu can be found on other home video releases (including the booklet accompanying Retaliation, but especially with how represented Seijun Suzuki is on Criterion, Masters of Cinema, and other Arrow releases), Hasebe’s career has not been as frequently analyzed. Both discs also provide new interviews with Jô Shishido (still alive!), who’s always an entertaining, irreverent subject (and who’s given to pulling out fake guns and scaring the hell out of interviewers).

I can’t recommend Massacre Gun too highly, except to genre enthusiasts, but Retaliation is really an exceptionally interesting picture, one with a true sense of the depravity of its subject and an uncommonly developed social conscience. Fitting, then, that that film should get the more worthwhile supplements and better transfer, making it an easy one to encourage everyone to check out.