One of the great joys of following The Criterion Collection and Masters of Cinema on a regular basis is the constant sense of discovery one experiences. Every so often, they’ll throw you something completely out of left field, often from a director you’ve never even heard of, that suddenly becomes sort of indispensable. Bakumatsu taiyô-den is one such film. One their website, Masters of Cinema introduces the film thusly – “Voted one of the top five Japanese films ever made in a critic’s poll by Japan’s leading cinema publication Kinema junpô, yet barely known in the West, Yûzô Kawashima’s richly funny multi-levelled portrait of Japanese society Bakumatsu taiyô-den [A Sun-Tribe Myth from the Bakumatsu Era] is a glorious rediscovery.” That’s a tall order, one the film more than ably fills.

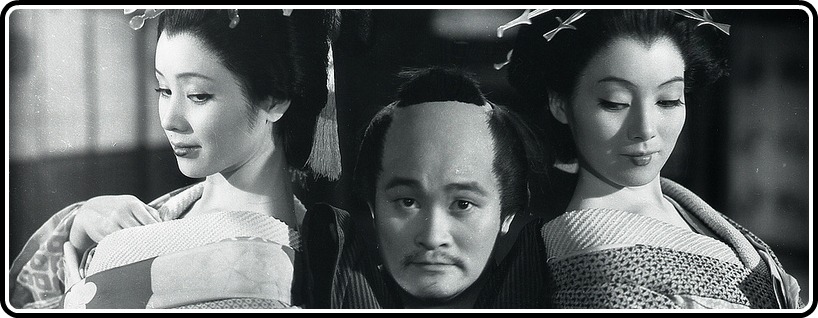

Following the comings and goings at a brothel in the 1860s, Bakumatsu taiyô-den is a relentless-paced comedic force that never really stops for an emotional turn, yet still has something of a profound effect. The closest character we get to a protagonist is a customer who, when he’s unable to pay a bill he’s racked up, is forced to go into the employ of the brothel, and comedian Frankie Sakai certainly makes the biggest impression in this role, but Kawashima is not content to simply let this be a showcase for his supreme talent. He gradually becomes the connective tissue throughout the film, the element at once unpredictable yet wholly reliable. We come to know samurai, prostitutes, a parade of other customers, and other would-be swindlers who just don’t have the ingenuity of Sakai’s Grifter. The film is stacked with any number of hilarious episodes involving double suicide, a lost pocket watch, promises of marriage, wasted youth, mistaken identity, pornography, daughters being sold, rival prostitutes fighting it out, and even a man posing as a ghost. Almost sounds like one of New York’s hottest clubs.

Yet what could be presented as a fun romp (and would succeed magnificently in so doing) is surprisingly contextualized right away with modern-day scenes in the very district in which the film takes place, noting that prostitution is on the cusp of being done away with in Japan. This is not to say the film takes a sunny view of its subject. It makes room for a certain boisterous atmosphere, but still manages to equally acknowledge the suffering of so many women, who end up pretty much as sex slaves in order to merely survive, driving many to rather extreme acts, never mind the actual imprisonment we’ll see later. Kawashima still keeps us laughing, even if it’s a defense mechanism to prevent complete depression. Not everyone who can illustrate suicide as farce, that’s for sure.

He may not display a particularly catchy visual style, but the way he choreographs his performers is masterful, keeping his performers constantly in motion to maintain a nonstop comedic force across 110 minutes (long for a comedy, but this manages it very well). Nevertheless, his is not the kind of work that will suddenly explode on Blu-ray, though Masters of Cinema’s transfer of Nikkatsu’s new restoration is splendid. Plenty of grain, great sense of depth, and very well-managed contrast (it’s a film of grays, not extreme whites or blacks, and MoC thankfully doesn’t push those ends too far), and I noticed nothing in the way of damage – whatever is there is far from obtrusive. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio, 1.37:1, and is locked for Region B. Screencaps courtesy of DVD Beaver. The sound mix is similarly simple and precise, with voices never dropping out even in the fast and furious arguments. In all, as perfect a technical presentation as one could ask for.

As these kinds of discoveries tend to go, there are no special features on the disc, unfortunately. The booklet, as MoC tends to go, does a nice job of making up for it, with a thorough essay by critic and scholar Frederick Veith and, even better, a piece on his personal and professional relationship with Kawashima by co-writer (and later, director in his own right) Shôhei Imamura. He spends a great deal of his piece noting everything he disliked about Kawashima, everything about which they disagreed, and the director’s much simpler strategies than those Imamura preferred and would come to employ. It’s a lot of fun to read.

Even in spite of the lack of special features, and even in spite of the relative non-reputation this film has in this part of the world, I have to give this disc an extremely strong recommendation. It’s one I expect to be revisiting quite often, not only to show to other people, but for my own viewing pleasure, so much fun it so thoroughly is. It’s completely unlike any other Japanese film I’ve seen, rivaling the masters of screwball comedy for its vividly realized comedic set pieces and relentless pace. Its quiet undercurrent of melancholy is its only familiar quality, and even that feels wildly different given its other trappings. I hope this release spurs on a movement to give it in the West the grand reputation it has in the East.