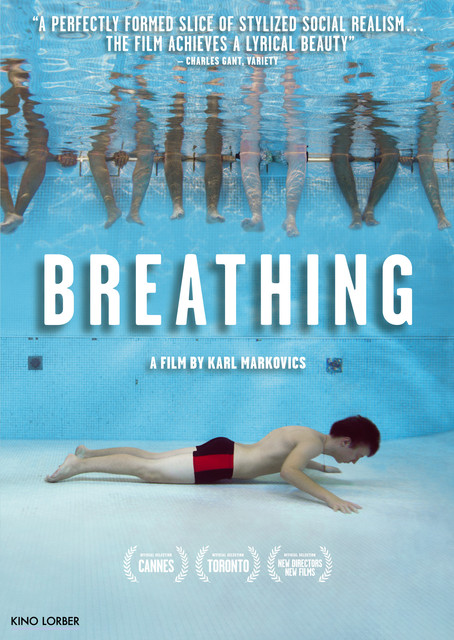

As film titles go, Breathing is about as minimalist and basic as it gets in regard to a chosen aspect of human experience. The breath is fundamental to our consciousness, our continued sense of individuated existence, from that first rude awakening of birth to the last gasp we give up before moving on to whatever’s next. And going back to its original German title, Atmen, only raises the profundity and broadens the scope, with its linguistic allusion to Atman, a core concept of Hindu, Buddhist and Jain philosophies. So it’s a bit on the audacious side to name a film Breathing, especially when the one in question is a directorial debut that also serves as the first on-screen feature performance for the young man who rarely leaves our sight throughout. The risk of falling flat or, worse yet, over-reaching for some grand gesture has to be dealt with, and fortunately for us, director Karl Markovics and actor Thomas Schubert do a commendable enough job pursuing their ambitions in this stripped down story of a young man coming to grips with the formative crises that reveal essential truths of his life and the world he inhabits.

That phase of late adolescence and young adulthood, in which we agonizingly begin to discover ourselves and make naive, impulsive decisions that define us for decades to come, serves as the inexhaustible pool from which many a script writer has ladled out the much-maligned “coming of age story.” I know that some readers would be happy to go the rest of their lives bypassing nearly all such cinematic offerings, but I don’t count myself among that company. I’m usually more than willing to go along with them, eager to appreciate new and interesting variations on the formula: stories from different cultures, times past, present and future, grim expositions of social realism or epic quests set in fantastic realms. A well-made coming of age tale finds fresh ways to connect with this universal rite of passage by incorporating unique formative experiences of the characters and new degrees of willingness on the part of the stories’ creators to risk investing themselves and their personal memories of those years for the sake of saying something they find important. Of course, the format doesn’t always work, and it’s easy to fall into some kind of derivative emotional hokum if mass appeal ranks too high on the producer’s priority list.

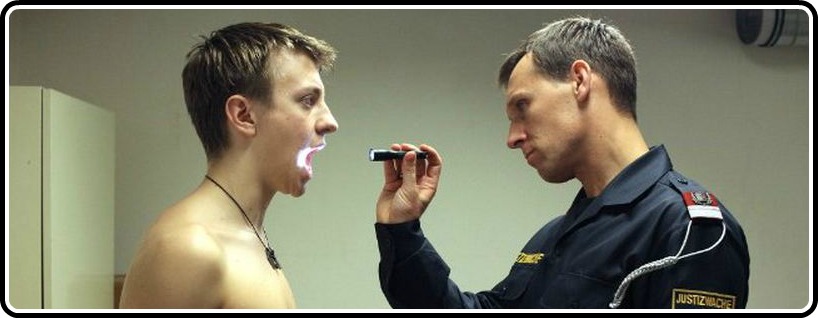

Breathing clearly belongs to the realist camp as it situates us in a surprisingly drab, nondescript Vienna, circa 2010, and the numbing mundane existence of Roman Kogler, a teen living in a juvenile prison as he awaits a hearing for his responsibility in the death of a peer several years earlier. Roman has spent practically his whole life in one institutional setting or another after being given up for adoption as an infant. The net result of this impersonal shuffling around through the Austrian child welfare system is a young man detached from everyone around him and unwilling to put forth any effort to make the situation any better for himself. He really doesn’t see the point.

Roman is nudged out of his isolated torpor into some kind of productive enterprise by Walter, his persistent but chronically overloaded case worker/probation officer. Walter knows that if Roman is to have any shot at a favorable release from detention and an opportunity to take on the world as a free adult, he’ll have to show his readiness by getting a job, maybe something in a factory. But Breathing‘s opening scene reveals that Roman isn’t fit to be a productive member of the assembly line, and soon enough, his morbid disinterest in humanity finds a fitting expression: he applies to work for a government run mortuary. The taunting of his jaded co-workers, most of them twice his age or older, Roman’s sullen lack of communication skills and the grim intensity of the work itself seem like a perfect set-up for failure. It might even be Roman’s subconscious way of proving to himself that this world has no use for a misfit like him. But the jolts provided by the experience of hauling off the dead lead him in various ways to reconnect with life.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rLPwjQKpdLk?rel=0]

Though there’s little in Roman’s persona to earn our affection (and I suppose there are some viewers who will find him so flatly drawn that they never find themselves caring what happens to him), his attachment problems become easier to understand as he begins to piece together vital clues about his long-hidden past. Having worked with a number of kids like him over the years, I deeply appreciate director Markovics’ resistance to making Roman more likable via cheap expressions of quirkiness or overtly angsty melodramatics. There are a lot of kids growing up like Roman nowadays in various child caring institutions all around the world – sitting back warily behind invisible barriers of not giving a shit and wondering why their life sucks anyway. They become too familiar with the routine of being passed from one sincere but ineffective caretaker to another. They see the commercialized pleasures, the material goods, the freedom to pursue grand adventures in this world (distilled here in a mockingly enticing travel ad posted in the subway station Roman travels from every day), but they quickly learn that those enjoyments are out of their monetary and vocational range, largely due to hardships imposed upon them when they were too young to have much say in the matter. They see the hard-eyed withering stare of the system’s enforcers, standing in wait to knock them back deeper into the hole that they’re trying to climb out of whenever they mess up by acting on old impulses hard-wired in.

Breathing gives us a palpable sense of one kid’s process of untangling the knot that his confusion, repression and early life insults produced. The cinematic elements and subdued soundtrack are handled in a way that lends careful discerning authenticity to the story’s telling. Roman’s aspirations are quietly, calmly recorded as they range from shallow inhalations staring into the cold eyes of a corpse, the convulsive gasps as the actual and metaphorical stench of death invades Roman’s increasingly acute senses and the release of reluctant bubbles at the bottom of a pool that refuses to allow him to drown. Cut from a similar cloth as films like Fish Tank and the upcoming release of The Kid With a Bike, this nearly bare-bones DVD may not get the attention that those two films have generated through their Criterion affiliation. Nevertheless, in a comparative competition of new millennium coming-of-age flicks, Breathing easily holds its own.