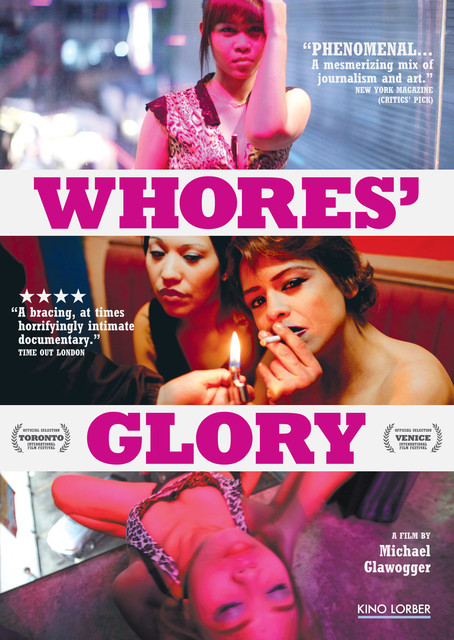

I can’t and won’t mince words. Whores’ Glory is probably the most difficult film I’ve had to process, digest and review in recent memory. The recently released Kino Lorber DVD was sent to me by my own choice – I selected it for the insight it would give me in regard to my profession in social work, where I train staff who work with young women caught up in this coercive nightmare – and I am truly grateful for the opportunity to watch it and have a copy that I can watch again and share with a select group of friends and colleagues. But it’s not a film that I can freely or casually recommend for the average movie-goer, even though I think that pondering its images and message will, with adequate reflection, deepen one’s insight into the human condition and initiate a cognitive process that will make one a more empathetic and overall better person.

The film’s title alone is challenging enough. In the realities that most of us inhabit, whores are not all that glorious, and the two hours of footage that director Michael Glawogger has chosen to share with us don’t deliver all that much glory either, at least not as it’s conventionally understood. The film, which he correctly labels as a “triptych,” takes us into three complex subcultures, simultaneously fascinating and horrifying for those of us who live in safer, more comfortable realms: brothels situated in Thailand, Bangladesh and Mexico, each one revealing its own particular brand of depravity and desperation, a gradual but inexorable descent into ever-descending circles of misery and oblivion, masked by rough orgasmic or drug-induced sensations to convince those suffering its torments that their plight is not really all that bad after all.

Though I haven’t seen the two films Glawogger directed to precede Whores’ Glory (and to be honest, I had no idea who he even was until I watched this one), it serves as a capstone of sorts to a trilogy he made as a statement on the effects of globalization and human exploitation in the new millennium. Megacities (1998) is a broad overview of life in New York, Moscow, Mumbai and Mexico City – four of the globe’s most imposing and incomprehensible metropolises. Workingman’s Death (2005) looks like it could be regarded as a companion piece to Godfrey Reggio’s Powaqqatsi in its focus the harsh conditions endured by the vast portion of humans consigned to work as low-wage laborers in some of the most dangerous working conditions on the planet. With Whores’ Glory, Glawogger strips away all pretense (in the most literal sense of that phrase) in confronting his viewers with the spectacle of carnal transactions of the most rudimentary, lust-fueled nature – “the world’s oldest profession,” as it’s so often been labeled, and one that all indicators dictate will effortlessly outlive us all, regardless of whatever outrage or dismay it might trigger in those who wish it weren’t so.

The path that Glawogger pursued in order to create Whores’ Glory remains, to me at least, mysterious and elusive. This DVD doesn’t really offer much in the way of explanatory supplements or background information as to how he chose his locations or managed to win the trust of those he captured on film. That inexplicable accomplishment is just one of the marvels of this film, as he achieves a degree of unvarnished candor and transparency with several of his subjects that must leave his documentarian peers and rivals gasping with envy. He traverses the complex subcultures of Bangkok’s highly commercialized, technologically advanced “Fish Tank” (where girls are tagged and numbered for male consumption like menu entrees at a fast food restaurant), the slums of a Bengali “City of Joy” district, and the rugged sleaziness of “The Zone,” a pothole infested strip on the outskirts of a Mexican border town where the prostitutes flaunt themselves to impress the men trolling by in their trucks, pockets bulging with cash and misogynistic fury. It’s quite likely that Glawogger himself had to fork over a fair amount of currency to the overlords who profit most directly from each of these establishments. Even without the completion of any sex acts, the footage he captures is a rare and valuable commodity, and I cannot imagine that he and his crew would ever have been given the incredible degree of access that we observe on the screen without making it worth the pimps’ and madams’ time to let them in. As impressed as I am by the film’s verisimilitude, it’s fairly obvious that some of the scenes are something different than strict “fly on the wall” observation. Everyone on the screen, almost all of whom emerge unnamed and completely anonymous at the end, has some skin in the game.

Though I’m mostly over it now, I acknowledge that I was pretty stirred up and antagonistic after my first full viewing of Whores’ Glory the other night. It’s a tough ordeal for anyone harboring more than a shred of empathy for our fellow humans to see even a hint of the full extent to which young women who, through no fault of their own, are born into a system that will devour and dehumanize them all for the sake of some relatively easy cash profits and fleeting pleasures. Listening to the boasting and blatant sexism of men who casually justify their role as customers in the business was nothing less than infuriating for me – full disclosure here: I’m a married guy who’s been monogamously faithful and happy in that relationship for 28 years now, so I have a hard time relating to guys who hit up the prostitutes on a weekly (or even more frequent) basis while also privileging themselves with steady wives or girlfriends back at home. Whatever kicks they may get, however “generous” or “philanthropic” even they may feel in their patronage of girls they express some affection for, I have a hard time accepting since the film (and my own life experience) has shown me the devastation that such cravings have left in their wake.

But before I go off on mere editorialism regarding victims of the global trade in sex trafficking and the inherent disrespect for women that makes such a horrific enterprise conceivable in the first place, let me shift the focus back to the film itself. Whores’ Glory is an impeccably well-crafted movie – the quality of the images, the editorial discretion, the profound slices of life it captures and the inherent wisdom (some of it spiritually grounded and emotive, some of it ridiculously wild, barbaric and vicious) it conveys make it among the most affecting cinematic works I’ve had a chance to watch lately. I would like to hope that the knowledge that comes from a careful viewing would move more people to act, but I’ll be the first to admit that the situation we see on screen appears way too deeply embedded, even vital to the local economy and cultural constructs that so many depend on in their respective societies, to hold out much hope that the situation will significantly improve in our lifetime. Indeed, the overwhelming impression I get from watching each of these segments of the triptych is that commercialized sex-for-hire is close to being part of the indigenous culture in these societies – as one of the Bengali men puts it (and I paraphrase), “if it weren’t for the brothels, women wouldn’t be able to walk on the street without being molested.” That is an outrageous reality to accept, but it is in fact a common perception that holds sway in more societies than Whores’ Glory has time to survey.

A significant portion of the frustration I felt in watching this film stems from the fact that the trauma and spiritual disconnection that I saw on the screen was so far away, so infinitely distant from any ability I had to address and improve the situation, even though it resonated so much with the unfortunate experience of clients I’ve worked with and friends I’ve known over the years. Another layer of futility grows out of the sad role that religion itself plays in placating and rationalizing the oppression that these women have taken upon themselves in order to make some sense of the chaos they inhabit. My main hope in promoting this film, with all the qualifiers that precede this final statement here, is that it will genuinely rattle us to re-examine how we regard women who have been forced by poverty, sexism and brutal domination to subject themselves to such miserable treatment over the course of a young and tragically wasted lifetime. Whores’ Glory is not an easy watch, nor is it anything approaching “entertainment” in the conventional sense of the word. But it is truly unforgettable and viscerally gripping cinema, fearlessly provocative and worthy of solemn contemplation.