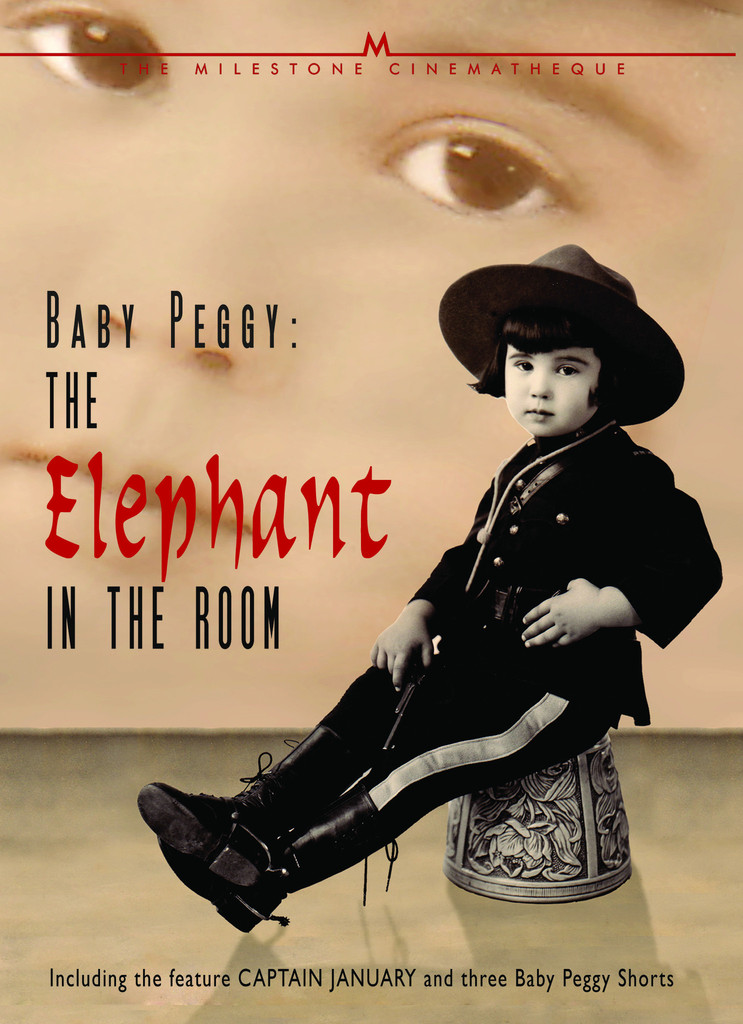

Over the past several years, it’s safe to say that fans of the Criterion Collection have had their cinematic horizons enlarged, almost by force, as the company continues its exploration of the early 20th century silent film era. Whether it’s the celebrated editions of early Charlie Chaplin and Jean Vigo, the recent acquisition of rights to Harold Lloyd (including the possible tease last week for The Freshman), a lavish box set of Josef von Sternberg features, Eclipse Series compilations of rarities from 1930s Japan or rescued-from-obscurity one-offs like People on Sunday, The Phantom Carriage and Lonesome, chances are near-certain that anyone who keeps up with Criterion has ventured into unfamiliar territory through these releases. Aside from the often brilliant artistry that went into the creation of these films, part of the enjoyment is in exploring the roots of many movie traditions that went on to become venerable archetypes in subsequent decades. The titles listed above cover a full spectrum of genres – slapstick, crime thrillers, domestic melodramas, romantic comedies, documentaries, even a ghost story, and viewing these early examples can lead us to better appreciate the tropes and customs that are now so familiar. One niche that Criterion hasn’t explored yet (unless you include their Hulu Plus exclusive of Chaplin’s The Kid, co-starring Jackie Coogan) is the early development of broadly popular family comedy, especially those featuring cute kids as their main focus. These aren’t typically the kind of films that we associate with the Collection, and just to be clear, I’m not really advocating for a deluxe annotated compendium of Little Rascals shorts festooned with the spinning C. But this week’s home video release of Baby Peggy: The Elephant in the Room definitely opened my eyes in a new way to the hardships experiences by child actors who are often dragged, quite naively, into a lifetime of psychological hang-ups and strained family relationships when they get caught up in the showbiz.

This hour-long documentary was first shown on the Turner Classic Movie channel in 2012, and as a standalone feature, it’s quite effective at informing viewers of a long-forgotten sensation who was, in her time, every bit as culturally influential as just about any other screen personality of the early 1920s that one could care to name. The main factors leading to her eventual obscurity were the lack of adequate preservation measures for the fifty-odd films she starred in between 1921-24 and her sudden disappearance just when she was at the peak of her popularity. With this DVD release, we’re given a chance to see a few of the films that have withstood the ravages of time so that we can discover for ourselves Baby Peggy’s undeniable magnetism.

Peggy Jean Montgomery was the youngest of two daughters born to a horse-riding stuntman and his young wife who had relocated from the American Midwest to Southern California just after World War I to find work in the housing boom associated with the rise of Hollywood and the general prosperity of the region. Through a series of unlikely circumstances, she fell into the acting profession and, as “Baby Peggy” experienced within the span of four years, a meteoric surge of popularity that propelled her to international fame, a fortune that was squandered almost as rapidly as it had been accumulated, and a sudden withdrawal from the film industry that was every bit as unplanned and surprising as her ascent had been.

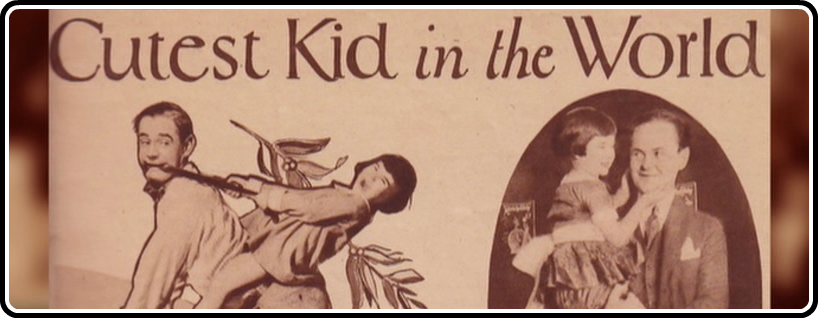

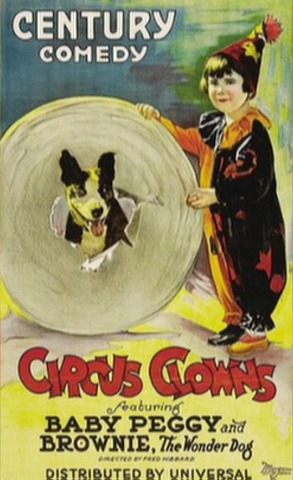

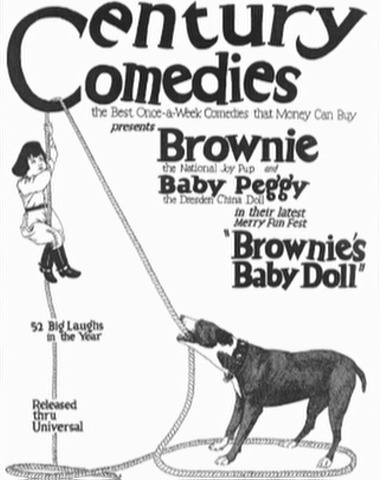

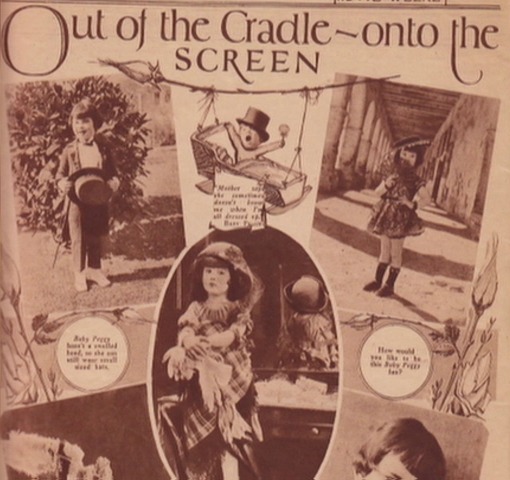

Though she might be all but forgotten now (except by those who’ve seen this film or who are smitten with the unique charms of this pivotal epoch of cinema history), Baby Peggy’s career has all the requisite elements of a legend that’s built to last into perpetuity. She was discovered in an almost offhand manner, as the story goes, when a director noticed how efficiently and unquestioningly she followed her father’s orders. Peggy’s combination of expressive disposition, photogenic body language and complete pliability on the set made her the ideal sidekick to another well-trained performer, Brownie the Wonder Dog. Their antics proved quite successful in provoking laughs throughout a series of amusing two-reelers that continued for several months until Brownie died. By that point, Baby Peggy had proven herself as a child comedienne who could hold her own without having to rely on a perky pup to keep the audience engaged. Her relentless energy and apparent zeal to soak up the spotlight quickly made her a popular sensation. The studios couldn’t crank ’em out fast enough to exhaust her enthusiasm for dressing up fancy and mugging on cue, and it was soon quite clear that Baby Peggy had a grasp on America’s “little miss sunshine” title that her rivals could only dream of snatching away.

The only limits on what Baby Peggy could accomplish were those imposed by a lack of imagination on the part of her writers and directors. She had a versatility and a willingness to position herself in just about any role they could dream up, almost as easy to configure as an animated character. Indeed, I had the sense of watching “cartoons cast in real life” as I watched the 10-12 minute shorts that accompany the title feature here. Peggy’s dress-up parodies of major Hollywood stars of the times like Pola Negri and Rudolph Valentino reminded me of the way that Warner Brothers employed characters like Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck later on in the 1930s and ’40s to lampoon their own cast of silver screen idols.

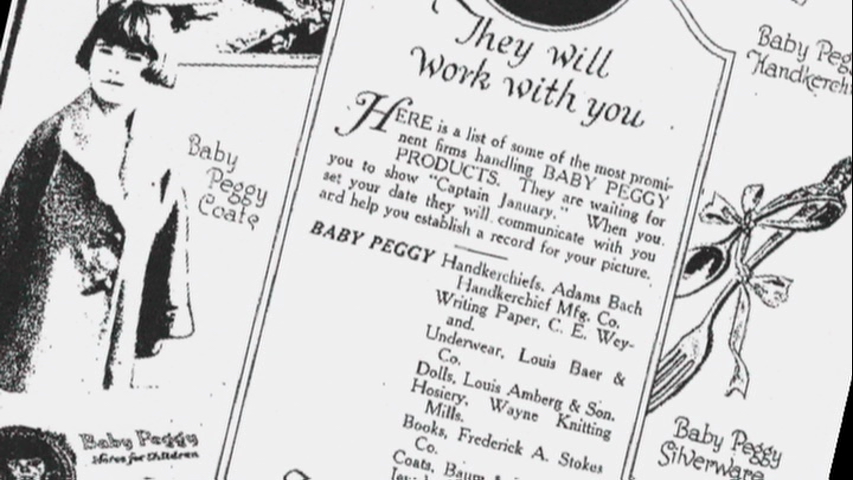

As Baby Peggy’s fame shot through the stratosphere, she became one of our earliest cultural prototypes for exploitative branding and merchandising. Her name was lent to all sorts of different wares, and it’s easy to imagine just how loose and shady the industry practices were back in those days, when trademarks, images and reputations were not quite as closely safeguarded as they are in our contemporary and highly litigious marketplace.

And just to prove that the appeal of an irresistibly charming and adorable kids transcends all borders and languages, Baby Peggy: The Elephant in the Room offers ample testimony to just how widespread her fame grew in that compressed span of time. Posters and other artifacts from across the globe were created and eventually collected decades later, a powerful demonstration of the effect that film can have in creating a meta-cultural ideal of childhood, or just about any other phase of human existence. Throughout this time, of course, Baby Peggy herself had no concrete sense of just how famous she was, or what made her youthful experience of life so distinctive from that of other boys and girls her age. Sure, there were a few other famous child actors in that era, but in truth, their numbers were extremely small and I doubt that any were as utterly ubiquitous as she seemed to be during the first half of the 1920s. But despite all that momentum, and the support of an industry that was certainly willing to ride the Baby Peggy train until it completely ran out of steam, the plug was pulled quite rudely and abruptly in 1924, by her father’s own obstinance. His refusal to honor the terms of her contract, after he mistakenly over-estimated her drawing power, completely derailed her career and threw the family into a death-spiral of financial reversals and heartbreaking loss. By the time Peggy was five years old, her peak earning years (an annual salary as high as $1.5 million in 1920s dollars) were already behind her. Relocation, bankruptcy, divorce and estrangement awaited Peggy and her family – a blunt and depressing reminder that regardless of how free and easy life may seem when everything’s in alignment, there are no guarantees that the ride will continue even one more day.

The second half of the documentary turns out, happily enough, to offer a redemption story as sublime and uplifting as any plot that might have been scripted by Hollywood’s most acclaimed talents. After being rudely abandoned by those who had profited from her contributions to the movies, Peggy went on to perform in the vaudeville circuit, carrying on like the little trooper she’d been raised as, shouldering the responsibility of providing for her family in a new way just as she had for as long as she could remember. Despite her dedication and obliging deference to do whatever Daddy demanded of her, it wasn’t enough to keep the family together, or establish her on the path to a happy young adulthood. She had a lot of hard knocks and heartaches to endure before she could finally come to peace with her journey. Part of that process involved changing her name to Diana Serra Cary, the identity through which she became a successful author and advocate for humane child labor laws as they pertained to the entertainment industry. Her remarkable poise, grace and wisdom as a mature woman living into the 21st century, one of the very last surviving stars from the heyday of silent cinema, lends indelible value to this film, elevating it above the usual rags-to-riches-to-rags stories that we’ve become so familiar with in tracking the tribulations of faded pop stars from the age of rock’n’roll. In particular, Cary’s serene insight and remarkable lack of bitterness regarding the hardships she endured directly as a result of her father’s ruthless and heavy-handed exploitation proved to be quite inspiring, even moving my 20-something daughter to tears as we watched the film last night.

As informative and thought provoking as the title feature is, it’s the inclusion of three vintage shorts and one of only a few full-scale feature films that Baby Peggy made in her all-too-swift perch atop the throne that make this DVD release by the Milestone Cinematheque such a vital, well-rounded package. (Milestone is a pretty cool company that has developed a fine catalog of rare archival films dating back to the earliest days of cinema. They also pull off a clever adaptation of Criterion’s old left-to-right horizontal line splash screen DVD opener.) Without the opportunity to see the child star take on and own a role from start to finish, her saga would mostly just prove to be a passing curiosity. The four titles we get here are released in roughly chronological order, starting with 1923’s Carmen Jr. in which Peggy plays a diminutive Spanish temptress who gets dizzy from the tango and slips into a crazy dream about bullfighting. Peg o’ the Mounted plants her up in the Yukon (actually, in the vicinity of Yosemite National Park) where she challenges roughneck moonshiners, including the 7′ 7″ ex-circus giant Jack Earle, with no particular objective in mind other than to stir up warm chuckles in response to the silliness of it all.

Such is Life, from 1924, admittedly drags a bit and serves most significantly to demonstrate just how crass and negligent Baby Peggy’s studio could be in simply thrusting her into any role, regardless of the story’s quality. It’s a loose adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “Little Match Girl” that sees her move from pitiful snow-dappled street urchin to spoiled little guest in a rich family’s home. The appeal of this short rests primarily in watching Peggy ham it up shamelessly – by this point, you’ve either fallen in love with the little imp or you’ve had your fill, at least for awhile.

The unquestionable gem of the set, and one that, in a more just universe would have received top billing (with the 2012 documentary included as a bonus supplement) is Captain January. It’s an hour-long “Universal Jewel,” indicative of that studio’s highest caliber, fully budgeted production at the time. The story is undeniably a bit on the mawkish and tear-jerking side, with each twist of the plot easily predicted and telegraphed every step of the way. But I say that in full admiration for its unapologetic sentimental appeal. It’s the story of Jeremiah Judkins, an old lighthouse watchman who one day rescued an infant from the pounding waves that killed her mother and marooned her in a shipwreck. He names the babe Captain January (presumably, the month she was pulled from the storm) and she becomes his trusted source of comfort, joy and companionship in his old age. Of course, their splendid idyll is too pleasant to carry on indefinitely and before too long, meddlesome busybodies from the harbor town decide that the little girl needs to be removed to an orphanage to be brought up more properly than the scruffy old salt could ever manage. Various tensions, intrigues and mirthful interludes are set up and carried out to satisfying effect, and in watching them, we get at least a brief glimpse at Baby Peggy’s delightful concoction of innocence, whimsy and pathos that made her rich, famous and, for awhile, miserable, before a measure of grace came into Diana Serra Cary’s life to teach her, and us, that there’s more to life than the amusing phantoms that dance ever so fleetingly across the screen.