Over the last handful of years, theaters across the country have been filled with documentaries of various levels of quality looking deep into the lives and work of various capital A artists. Be it the brilliant Tall: American Skyscrapers and Louis Sullivan or the insufferable Julian Schnabel: A Private Portrait, the rise of biographical documentaries looking at influential artists has seen some genuine highs and some frustrating lows.

And then there are films like Beuys.

To most people, the name Joseph Beuys means little to nothing. A formative German artist, Beuys was a figure whose import range from political revolutionary to someone more at home in an asylum than an art gallery, and director Andres Veiel has a hell of a subject for his new documentary, and does his able best to introduce the viewer to the man and his work. Using primarily archival materials, much of the picture sees the subject speaking for himself, particularly focusing on the artist’s battle with depression during his early days as an artist. Here the film brings to light some of Beuys’ early illustration work, and from there the picture evolves into an intimate portrait of a creator perpetually in crisis.

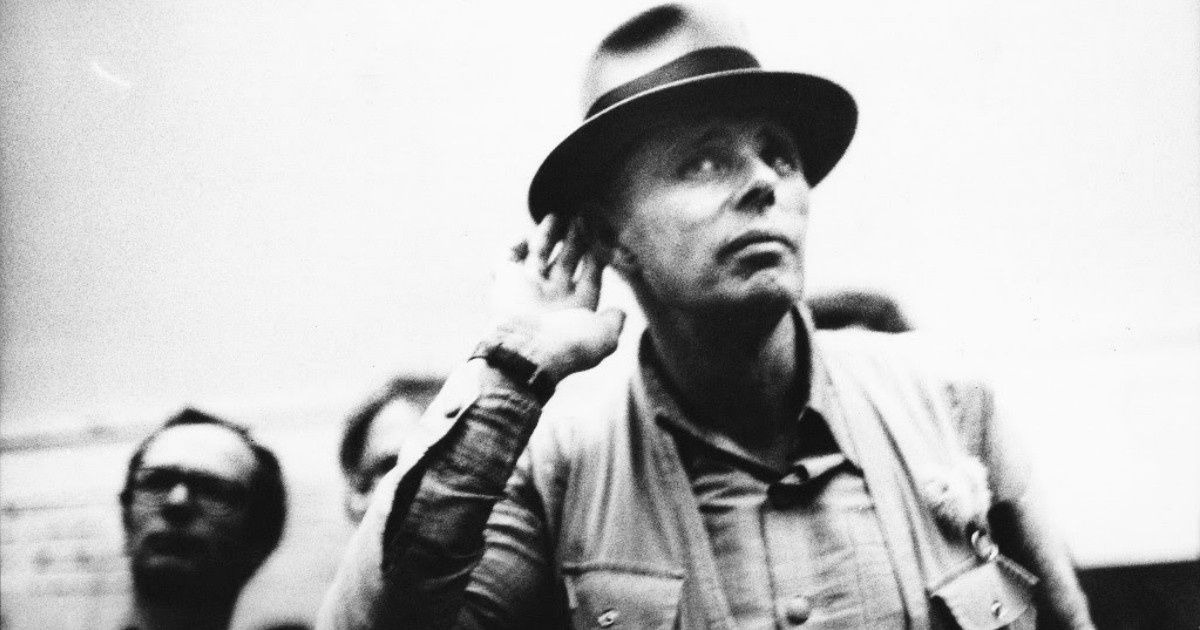

However, while Beuys is an inherently compelling film and Beuys an inherently compelling figure, director Veiel does little to really break free from the ever growing world of biographical non-fiction filmmaking. Beuys’ first hand account of his life and work are inherently interesting and compelling, but what isn’t is the editing or overall aesthetic of the film. Adorned with his trademark fedora, Beuys is front and center, but so are cumbersome talking head interviews that do little to add much context that isn’t added by the compelling archival materials. Be it interviews with the artist or his actual work spanning his entire life, these are the moments where the film really jumps off the screen, and battling with this work and this artist are the real heights of the picture. He is, afterall, best known as a proponent of the “everything is art” ideology, and while that’s battled with only superficially, hearing the artist confront almost primordial artistic questions are when Beuys is at its most entrancing.

That all being said, this is a truly important piece of work. While not all of it hits on all cylinders, what it does do well is give an insightful and compelling look into the work, and more importantly the life, of a great, unsung artist. Even to the most studied art aficionado, Beuys is a less than well known entity, and the questions the artists spent his life attempting to work out are ones that face artists spanning generations. Sure, some of his performance pieces may seem cartoonish (I Like America and America Likes Me is on the surface a ludicrous piece of art and something that feels a kin to a Simpsons-style pastiche of avant garde artwork), but Veiel gives the utmost respect to the art and its creator, something that is both admirable and important. Because while some choices here may not make for a completely compelling 100-plus minute viewing experience, great respect is given to the art at its center, and with equally thoughtful context about the artist’s life, what results is a simply made yet thought provoking piece of non-fiction filmmaking.