There are few narrative tropes seemingly less interesting in today’s film world than the “men behaving like children” subset of film comedy. Be it the Apatow suspended adolescence comedies or the vulgar auteurism (using the actual definition of both of those words and not the confoundingly ridiculous critical term) of Todd Phillips, cinema has become flooded with tales of men at their worst seeking some sort of redemption while never quite maturing in the process. That is, until director Athina Rachel Tsangari jumped into the fray.

While fellow Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos has garnered the majority of headlines out of the seemingly still young New Wave of Greek cinema, it has been Tsangari (who helped produce Lanthimos’ masterpiece, Dogtooth) who has brought to the screen some of the most exciting films out of Greece in ages. Debuting with the impossible-to-see The Slow Business Of Going, it took her roughly 10 years to break onto the scene as a filmmaker, with the brilliant Attenberg, and now she has returned with arguably her greatest achievement to date.

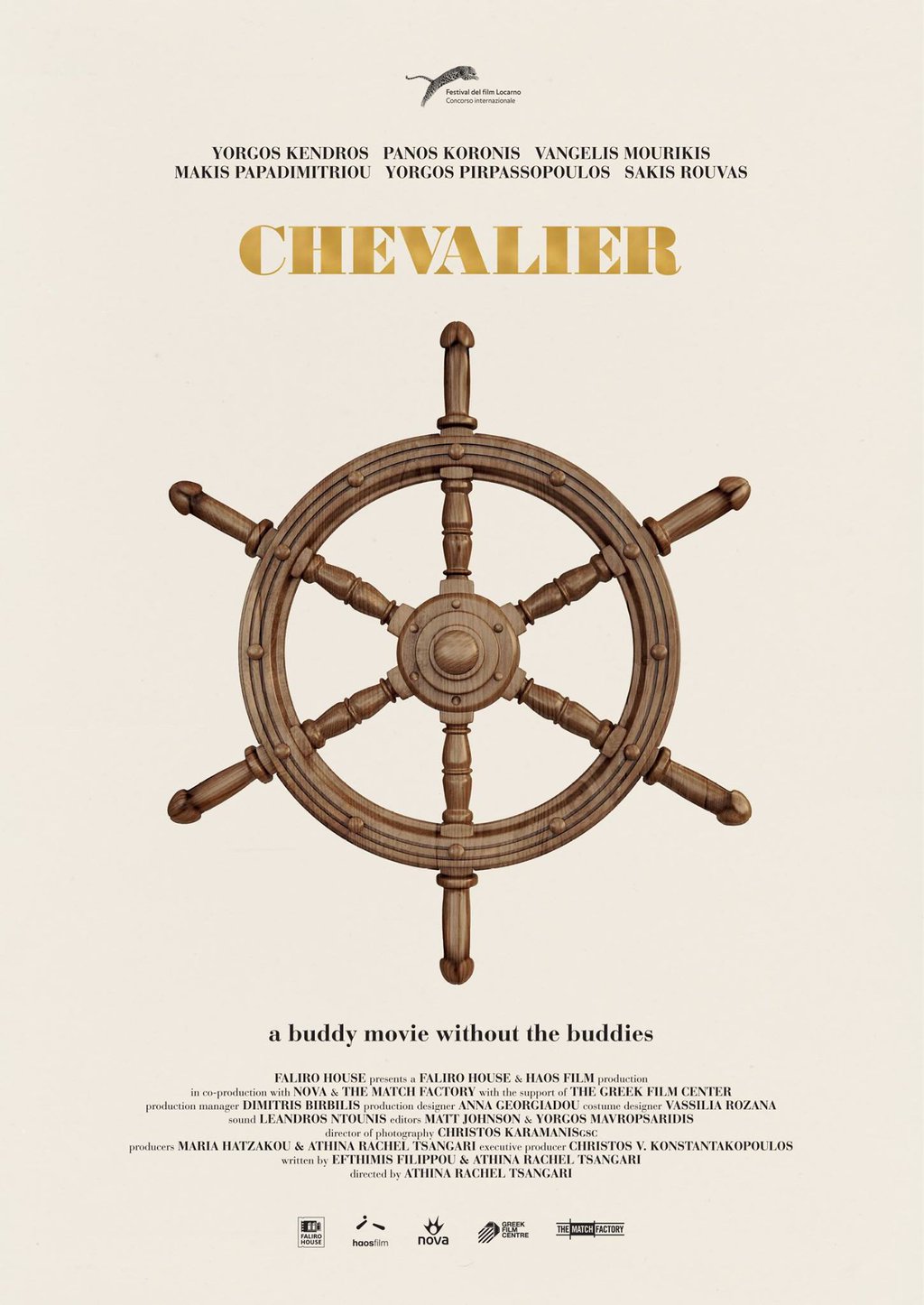

Chevalier has a relatively simple conceit. The picture introduces us to half a dozen men of various ages and tax brackets, although all appear to be of some affluence and knowledge of one another (or else how could this trip have taken place). Set aboard a ship somewhere off the coast of Greece, the film has a small scale, and yet when the men begin a game to test a handful of talents, our story dissolves into a profoundly comedic and provocative look at masculinity in a country driven to the brink of complete collapse.

Among our principal cast are Yorgos Kendros’ “Doctor,” a wealthy man on the “back nine” of his life, and the brother duo of Dimitris (Makis Papadimitriou) and Yannis (Yorgos Pirpassopoulos). Christos (Sakis Rouvas) is married to the doctor’s daughter, and the cast is rounded out by the resident alpha male of the alpha males Yorgos (Panos Koronis) and Josef (Vangelis Mourikis) resident partier and lothario. In the film’s earliest moments, these broad strokes are the beats being played, but as the briskly paced black comedy progresses, we discover that not only is this a film of breathtaking nuance, but it’s also a lushly composed and taut comedy, of sorts, that evolves with each new and more histrionic test of masculinity.

That’s ultimately the film’s narrative structure. As we are introduced to the cast of characters, the men begin to take upon themselves a series of tests, a game in which every aspect of one’s life is potentially the root of a comparison to the person standing next to you. Be it building a shelving unit for seemingly no real reason outside of testing who can do it faster and with high quality or a literal testing of one’s, ahem, manhood, the film jostles from the purely comic to the quietly moving without much of a shift in mood or atmosphere, making each contest feel of the same narrative and culminating in the same thematic discussion. As we see the men take these challenges on with a life or death sense of urgency and importance, pettiness arises, and the film truly comes to life in the second and third act, with a ritual sequence playing as one of the most comedic set pieces seen on screen in quite some time.

Tsangari, who directed her first film roughly 15 years ago, is one of the most interesting filmmakers in world cinema today. Where her counterpart, Lanthimos, makes films that are decidedly surreal and have a tactile sense of absurdity to them, Tsangari’s films are rooted far more in the type of films seen out of Eastern Europe, just with a slightly quicker heartbeat behind them. This film especially, with it’s lush photography and quiet direction taking place across one intimate setting, feels right out of Romanian cinema of this decade, and the dry sense of humor is an equally important quality shared between them. That is to say, the film doesn’t shy from absurd moments. Much of the humor has its absurdist beats (like a nighttime break dance sequence) but it all feels as though it comes from a slightly different place than the deeply troubling surrealism of a film like Dogtooth.

All things being equal, Chevalier will find a happy home in arthouse cinemas and on VOD through various platforms. A quietly told comedy for the #masculinitysofragile age, Tsangari has made a deeply profound, if slightly overlong (at roughly 100 minutes it does tend to drag near the end of the first act), meditation on manhood and modern masculinity.

Mon, Feb 15, 2016 at 8:30 PM (Regal Fox Tower)

Tue, Feb 23, 2016 at 8:30 PM (Roseway Theater)

https://youtu.be/lkmN1WnysUE