There are few filmmakers alive today more worthy of a biographical documentary than one William Friedkin.

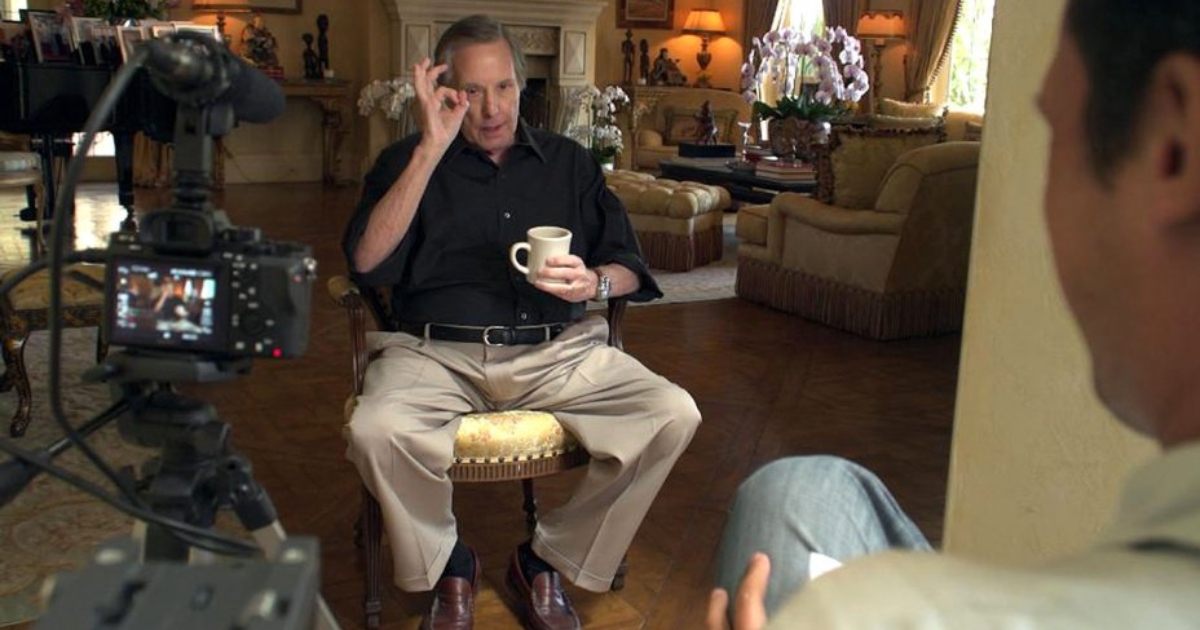

Nicknamed Hurricane Billy by those who worked with the director as he broke onto the scene, the French Connection and Exorcist auteur is the latest filmmaking figure to get the once over via documentary. Akin to films like De Palma, Friedkin Uncut sees the filmmaker sit down for a chat with documentarian Francesco Zippel, chatting about everything from the reception of The Exorcist to his pivot into documentary filmmaking with The Devil And Father Amorth. It’s just too bad none of it amounts to anything all that insightful.

While he and the aforementioned Brian De Palma have similar, shall we say, temperaments, Friedkin Uncut falls completely flat in comparison to De Palma’s titular biodoc. Shot flatly by Zippel, Uncut tells a relatively chronological yarn, going point by point through the highs and lows of the director’s storied career. With a killer collection of supplemental interviews including names like Francis Ford Coppola, Willem Dafoe and William Petersen, the film has all the makings of a captivating biography. However, none of it matters, ultimately, as what’s being asked of each party involved is barely negligible.

The film falters due entirely to low ambition. Most of the film revolves around his greatest hits, rarely breaking off to discuss the more curious entries in his career. There’s a lack of real narrative here, as the supplemental interviews break rarely from the “he’s the best director I’ve ever worked with” mold, even when someone like Juno Temple mentions Friedkin taking off his pants during the shooting of a scene in Killer Joe. It’s a moment like that, a moment of perverse performative masculinity that should, in a good film, be a launching point for a dissection of the generation that gave birth to he and his equally bombastic brethren, yet it’s played as some sort of auteurist stamp. A curious moment that shows his connection to his performers. It’s a proto-typical vanity project that begins with an eye-roll inducing comparison between Jesus and Hitler, a moment played as profound but only begins the film with a giant sigh.

It is a welcome change of pace once a film like Sorcerer is mentioned, a film with a rockier history with regards to its stance critically, yet even here the film doesn’t do it justice. The entire discussion surrounding the film is split between its tough shoot and its reappraisal as maybe Friedkin’s magnum opus, the exact conversation that’s been surrounding the film for the better part of the last decade. At best, Friedkin Uncut is a serviceable EPK on whatever Friedkin film is set to get yet another Blu-ray release. However, anyone looking for a smart discussion about this generation of filmmaker will be disappointed and any cinephile looking for incisive discussions about incredibly strange films like Bug will be left with something even worse; boredom.