It’s the sign of a truly special documentary that, some 50+ years after its initial release, it feels as vital and vibrant in 2019 as it did during those first premiere screenings.

Released in 1968, director Frank Simon’s The Queen is one of those rare, incredible and groundbreaking documentaries.

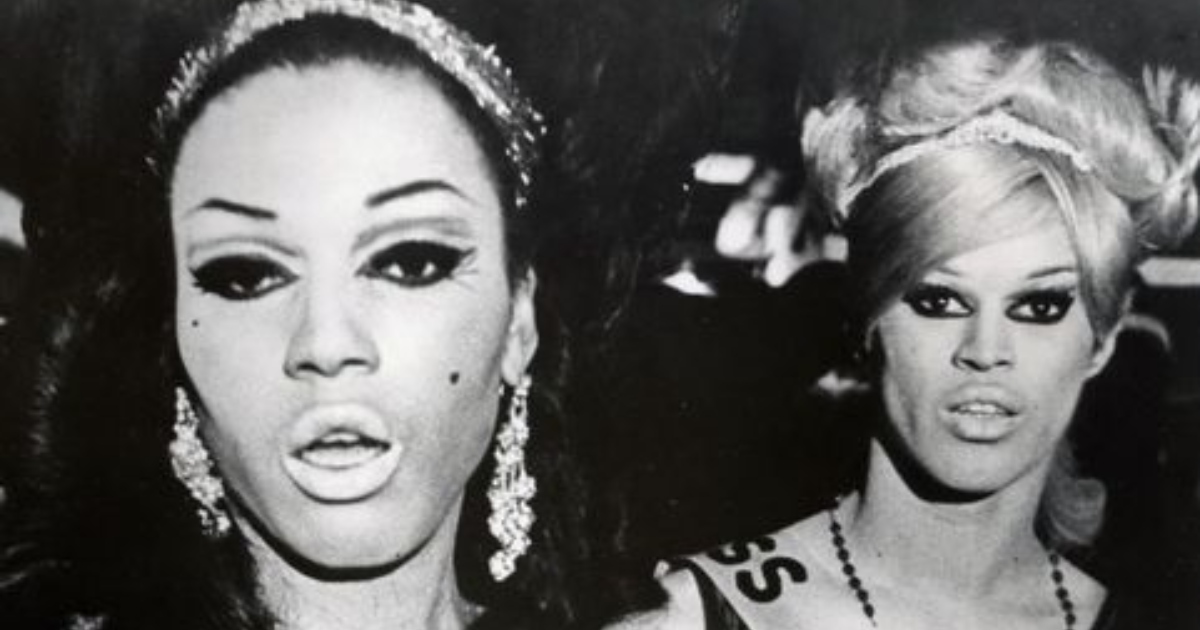

Back in theaters thanks to a new restoration spearheaded by the folks at Kino Lorber, this lively documentary shines a light on a subculture that only recently has hit the mainstream. Decades before Paris Is Burning and shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race, The Queen takes viewers into the world of the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant, a competitive drag contest. At just a pinch over 60 minutes in length, this brisk, energetic documentary is being paired theatrically with the incredible short film Queens At Heart, and makes for one of the most rewarding and eye opening evenings of non-fiction cinema one has seen yet in 2019.

Newly restored in glorious 4K, The Queen is both an important queer cinema text and also a provocative non-fiction piece in an era of stayed, rudimentary talking head films. In theaters just a week after a film like Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, The Queen plays in stark contrast to that clinically made film. Simon’s direction is intimate and alive, with the 16mm popping off the screen at every turn. Rooted heavily in the verite style that sparked just under a decade earlier with films like Primary. Released in the same year as Salesman, this is a definitive fly-on-the-wall type documentary that offers up intimate conversations with performers and organizers at a moment in history where such gender-bending was outlawed in New York outside of theater performances. Close ups abound here, and the camera is rightly as vibrant and energetic as the performers it focuses on.

It’s also an immensely important queer cinema text. Besides being a captivating watch aesthetically, much of the context surrounding the film remains profoundly important. A moment in queer culture pre-Stonewall, the film never turns away from difficult topics such as gender reassignment surgery or the racial component of drag in late 60’s New York City. With each of these conversations playing out as raw and unfiltered, the film carries its aesthetic energy through to a sense of intellectual intimacy that’s rare even today. We watch as the performers prepare for the contest and deal with the ramifications of their art, as well as apply their craft resulting in some of the more entrancing performance sequences you’ll see in all of 2019.

There’s a particularly moving moment during the conclusion of the film that plays superficially as the lament of a performer given a second-place spot, but in actuality is an incredibly aware and moving moment of aggression. The person giving this tirade is none other than Miss Crystal LaBeija whose House Of LaBeija would become a main focus in the incredible documentary Paris Is Burning and while the screed does feel rightly performative it also hints at real and important racial dynamics within the community. Her complaint about being passed over for a white performer even though she feels like she put in exponentially more effort is both raw in the context of a runner up feeling rejected and even more transgressive when the racial component she brings up feels unresolved even to this day. It’s a shattering sequence in a film that is chock a block with unforgettable moments. The other crowning set piece involves a group of performers discussing the merits of going under the knife for gender reassignment surgery. This is an important conversation within the context of the film as its one of the more explicit glimpses into the life of drag performers and what they see as their art. Never once are these performers seen as anything less than self-aware artists, and this first-hand account of their experience in pre-Stonewall NYC is an essential and urgent piece of anthropology, even 50+ years later.