While it may seem like, in the age of Bernie Sanders and the burgeoning Democratic Socialist movement, that socialism and specifically the thread of that belief system born out of labor movements and economic disparity is a new fad in American politics. With members in the tens of thousands, the DSA has become one of the most influential and important wings of the Democratic Party, and to many millennials thinking they are on the cusp of something entirely new, the idea that the roots of American socialism run deep into the DNA of American politics is confounding.

Which is why The Prairie Trilogy is as important a documentary series as you’ll see all year.

Made up of three short films, The Prairie Trilogy comes from famed documentarians John Hanson and Rob Nilsson (Northern Lights), and introduces viewers to Henry Martinson who is as a rare a bird as they come. Originally shot from 1978-1980, the three films include Prairie Fire, Rebel Earth and Survivor, all in their own way shining a light on Martinson and his life as a poet, artist and more importantly a labor organizer and an original member of the Socialist Nonpartisan League. The SNL began in 1916, and its formation is the main crux of the first short, Prairie Fire, turning into more of a verite style look at Martinson’s life as an organizer in then current day North Dakota.

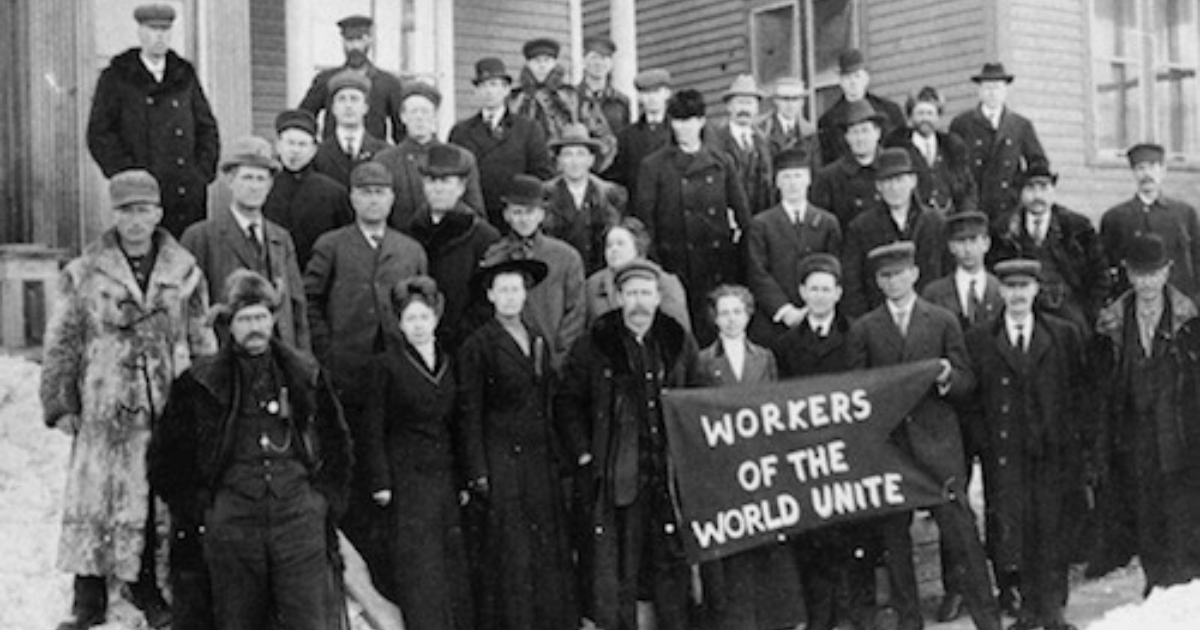

When taken as a whole, Prairie Fire is an incredibly singular premiere chapter. Built similarly to a feature like Dawson City: Frozen Time, Fire is a captivating mixture of sound and archival footage (shot by director Nilsson’s own grandfather), playing like a briskly paced and breathlessly vital proto-biography. Focusing squarely on the formation of the SNL, the film is as timely a work as ever, particularly when one embraces the endless energy within each frame. The black and white photography looks great here, as each short has been given a new 2k restoration, and watching activists push for economic and social changes still being fought for this very day is an exciting skewering of the idea that this sort of thinking is at all groundbreaking.

Beginning with the second film, Rebel Earth and flowing into the finale, Survivor, the style dramatically shifts. From focusing on the foundational history of this specific movement, these two shorts evolve into something closely resembling that of a filmed biography. Both of these shorts are gorgeously composed, each trying to get a different and fully formed view of the man himself. The first film pairs Martinson up with a younger farmer as he attempts to trace his steps through the life he lived. In Survivor, Martinson is again the central focus, shining a light on both his time as a socialist advocate at the dawn of the 20th Century and ultimately his time as a member of the SNL. A homesteader, activist, artist and even the state’s poet laureate, Martinson’s life was one fully lived, and while these documentaries are quite short, they give a fully formed insight into a man unlike any other.

Opening on Fire, this feature assemblage of these three shorts is a transcendent experience. Fire is a riot of a documentary, with its tone jauntier than one would expect, thanks to a rich mixture of archival photography and the occasional folk song. This is ultimately an anachronistic way of opening as the two subsequent documentaries feel more in step with the moment in non-fiction filmmaking in which they were made. More or less a document of Martinson recounting his life and sitting down with those closest to him to break bread, traveling the state with the filmmakers and trying to bring about one last burst of change before he kicks the bucket.

The energy in these two shorts is much lower, but Martinson is such a captivating screen presence that it more than makes up for it. There’s simply something deeply beautiful about the boundless optimism and hope Martinson has, in these films, for the future despite being on the brink of Reaganomics and the “greed is good” generation. Across these shorts Martinson can be seen and heard waxing poetic about the beauty of socialism and the labor movement he was thrust to the forefront of, and also about how at the end of the day the socialist movement will rule the day. And why wouldn’t he be optimistic? As he rightly points out, this very moment, no matter how slow the victories came, won everything from the battle over pensions to the fight for a strict, 40 hour work week. Therein lies the subtle beauty of this short film trio. While thousands upon thousands of people are turning to what they believe to be a groundbreaking socio-political movement, they don’t stop to realize that this type of worker-focused ideology is at the very heart of the American political experience. Maybe not as those living in 2018 think of socialism, but the DNA runs deep and runs clear.