In the world of art, the struggle between critic and artist is often anguished and eternal. However, throughout at least the history of film, numerous critics have themselves ventured behind the camera, even going as far as making some of the very greatest films within the medium (shout out Godard). While one should never “listen to the critics,” it appears as though some students of the medium through a critical lens have a knack for the artistry of it as well.

Therein lies Kent Jones, a staple of the New York film critic and film programming scene, who is leaping from the world of not just film scholarship but also documentary filmmaking, tackling his first narrative fiction feature Diane.

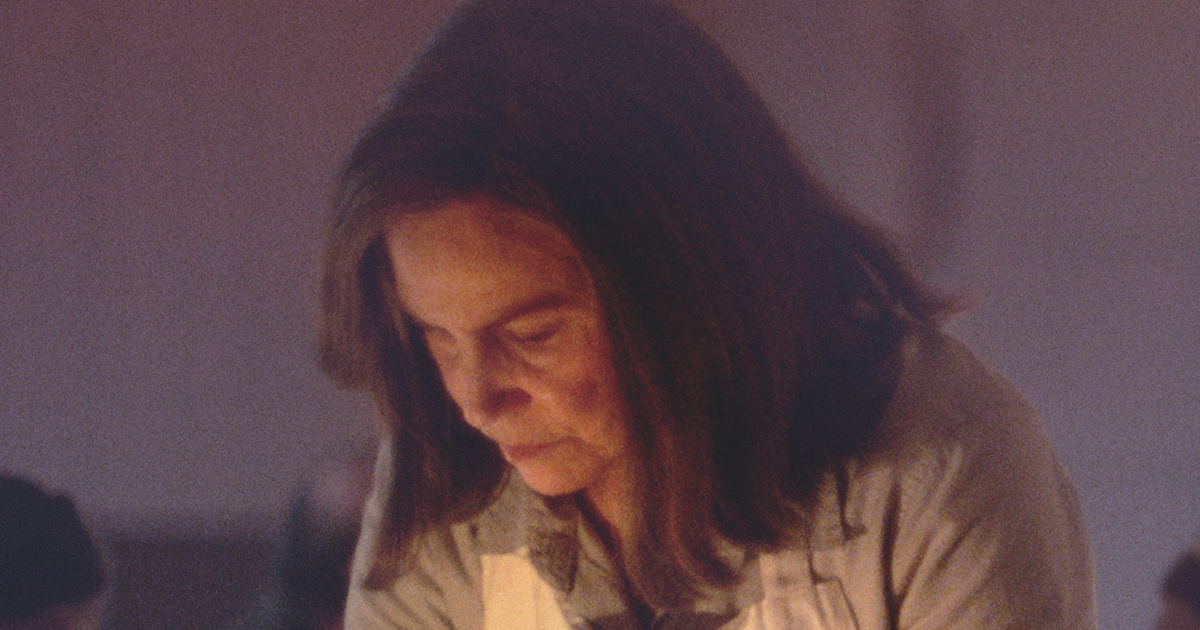

Starring Mary Kay Place, Diane tells the story of, that’s right, Diane (Place), a woman with a passion for bringing about joy in the lives of everyone except, it appears, herself. As often found at her local soup kitchen feeding those in need as she is at the bedside of any of her ailing friends, Diane appears to be one of the rare forces for good in this world that feels almost otherworldly in both her selflessness as well as the enjoyment she appears to get from that very concept. The rare soul that feels at complete peace sitting by the side of a sick friend for whom she just baked a fresh casserole for, without any request, Diane isn’t all smiles and helping hands, however.

Under the surface (boiling over quietly in moments thanks to a career-best performance from Place), Diane is a deeply troubled individual. With a cousin on the back nine of her life thanks to a cervical cancer diagnosis and a son with a nasty habit for kicking and picking back up heroin (played by another actor, Jake Lacy, giving a career-defining performance), Diane’s life is at a moment of true upheaval, and through director Jones’ humane and humanist direction viewers become privy to a film about love and memory as the end of the road nears.

After seeing Diane, it should be relatively clear as to why Kent Jones was such a beloved scholar and film curator. A staple of the video essay world (in this house we stan his video essay on Criterion’s Week-End release), Jones also directed the top-notch documentary feature Hitchcock/Truffaut, and now he has to his credit a beautiful and naturalistic rumination on grief and guilt. Clearly showing reverence for his influences like Paul Schrader (the use of close-ups and the film’s editing style is very much in conversation with, particularly, late period Schrader, think First Reformed but exponentially less cosmic), Diane has the trappings of a James White-like slice of life drama, but feels more along the lines of recollected memories than anything resembling 2019 neo-realism. There’s a lack of fussiness to each frame that feels at once refreshing and also decidedly intimate, particularly when put to use in a film about more or less making due with what one has been given in that day. The static camera feels also connected to the work of Schrader, as the focus on objects and ritual shares a tight connection to that legend’s filmography. Wyatt Garfield shot the piece, who is himself best known for lensing intimate, very interior dramas such as Mediterranea and the vastly undervalued Beatriz At Dinner. His photography is absolutely top notch, and while it’s a bit less impressionistic than his work on something like Mediterranea, each frame carries with it a lived-in quality that only amplifies the film’s quiet drama.

It’s an unassuming film, until it’s very much not, specifically in the scenes between Diane and her son, which are more or less the crux of the film’s drama. These are scenes of incredible violence, not in any real physical way but the anguish as seen through the performances from both Lacey and Place is palpable and unshakable. They’re triumphant turns from two generational talents, with Place particularly flexing every muscle in her body for this role. She gives a performance that’s often very funny, a performance that’s often very quiet and yet every beat feels of a piece and getting as close to whatever the concept of “truth” in acting actually is. There’s not a false moment in her time on screen, and it’s a performance that’ll likely get forgotten come awards time because for some reason this is the worst of all timelines. Lacey is also quite good, although a pinch more uneven than one would hope, which in turn could be a benefit as this is a character that’s never quite in the center. Fluctuating from one extreme to the next, we watch as Lacey’s Brian kicks heroin only to become addicted to the original drug, G-O-D himself, marrying into a world of devout religion. There’s a particularly captivating exchange between the two when emotions explode in a way viewers have been waiting an hour-plus to see. This is a slow burn of a drama, but boy, when it burns, is it utterly unforgettable.

For more on Diane, check out David Blakeslee in conversation with director Kent Jones.