Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg, now returning to theaters for its 40th anniversary in a startling new 4k restoration, is that rare cinematic achievement that arrives, as unknowable as it may be, as less a series of events that convey a story, and more like some sort of religious text, expressing the authors worldview.

I mean, just take it from the man himself. Speaking to RogerEbert.com for this new theatrical run he said:

“My goal was to convey the concept through the film while minimizing the focus on the characters and the story. The characters, as well as the story itself, are merely symbols—materials for visualizing metaphors. When I made this film, I believed it was possible to express that idea through cinema.”

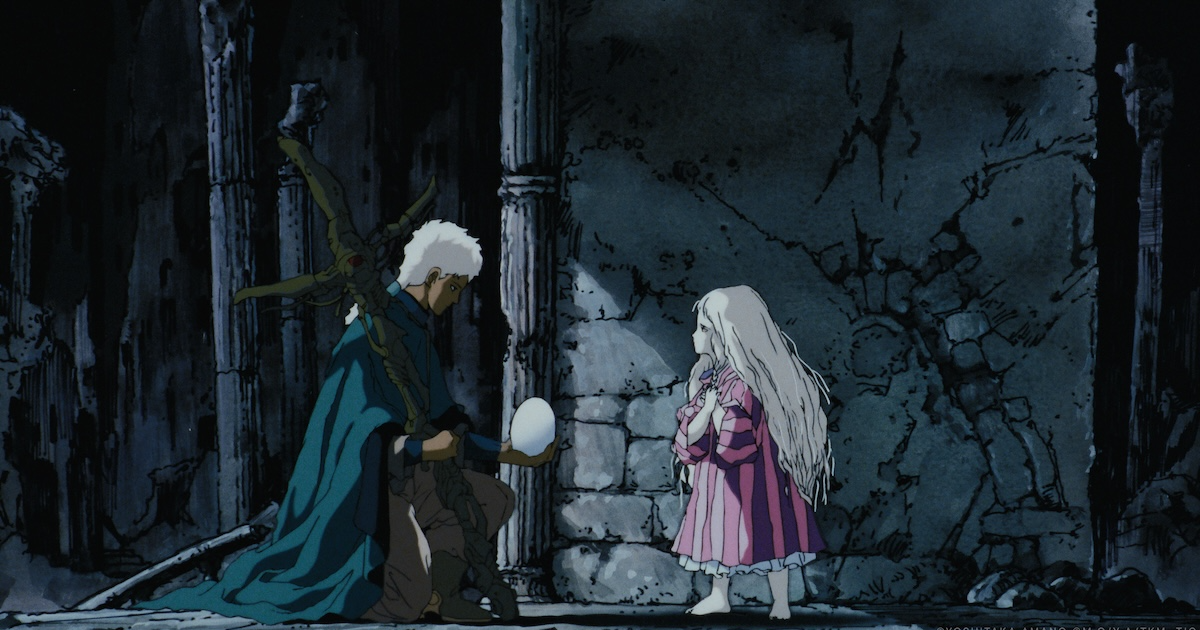

Standing in stark opposition to a recent run of (in their own right great) anime features like Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc (which, again, it must be said is absolutely one of the year’s great films) that have broken at the box office, Angel’s Egg feels no less like a bolt of lightning than it did upon its release in 1985. Created in collaboration with celebrated illustrator Yoshitaka Amano, the features minimal dialogue and a world that seems to exist entirely fossilized. Petrified. A young girl protects a mysterious egg with sacred intensity, like that of a priest maintaining a place of worship far beyond its viability. A man with the build of a warrior, carrying a cross-shaped staff/rifle to match, meets her. They speak in fragments, wander among colossal statues and empty Gothic structures, and search for something—perhaps a bird, perhaps a truth, perhaps God. The film does not clarify. It refuses to.

It’s in this place of abstraction that the film truly reaches transcendence. Interpretations over the years have proposed Christian allegory, Gnostic myth, autobiography, and even political metaphor. Ask the filmmaker himself, and he’ll say otherwise. Oshii himself famously rejected any singular reading, as if to insist the work must remain an open wound of symbolism. The egg becomes more than a plot device—it is a container for whatever meaning a viewer is willing, or desperate, to place inside it.

The girl’s devotion to the egg is unwavering, though she seems unable to explain why she believes in it. Her conviction is pure but not reasoned. It is here that Oshii’s film transitions from opaque symbolism to a devastating inquiry into faith: What does belief mean when we cannot confirm that the object of belief exists? How do we survive when faced with the ultimate question? Meanwhile, the soldier embodies the opposite belief, but with no less certainty. He does not mock her belief, but he questions it. There’s an expression on his face that suggests a man who has felt faith before and lost it. When he makes his ultimate decision (I won’t say what it is, but one second into him being on screen and you know how this relationship ends) it is an act as shocking for its spiritual consequence as for its narrative abruptness. He has not merely acted violently; he has shattered a worldview. It remains, even on what was my maybe fifth or sixth watch, one of the most upsetting moments in the canon of not just anime but film itself. It’s a profoundly moving moment.

And yet the film doesn’t play as a tragedy. Instead, the young girl is reborn as something more. The film offers no vindication for the boy and no condemnation for the girl. It is not a parable about the foolishness of blind faith or the superiority of skepticism. It is instead a lament that belief, doubt, and the longing for certainty might coexist in a world that offers none.

That this film returns in 2025 is not a coincidence of anniversary scheduling but a statement about the medium’s expanding self-consciousness. Anime has undeniably entered a global box-office boom, where event releases regularly rival Hollywood franchises. Audiences are turning out in record numbers for high-intensity, serialized cinematic experiences—violent spectacle, emotional crescendos, IMAX-scale battles of demons and devils. Against this backdrop, Angel’s Egg is hitting at the exact right time. It suggests that animation can still be metaphysical, inscrutable, and indefinable. That a cult OVA from the mid-1980s can receive a wide theatrical revival 40 years on proves that growth in anime viewership has not only expanded commercial appetite but also widened what the audience will spend their hard-earned dollars on. The market can now sustain not just the anime that explains itself, but the anime that asks us to sit with what cannot be explained.

Speaking of that 40-year revival, the new restoration is something truly special. Already one of the most beautiful anime pictures ever made, this new 4k restoration only cements it as one of the highest achievements in all of filmed media. The atmosphere is rightly oppressive, with the dystopian landscapes playing perfectly into the hand of Yoshitaka Amano. I spoke earlier of a set piece involving what originally appeared to be statues but now are fishermen hunting ghostly whales through the abandoned streets of an abandoned city in an abandoned world, and it’s in this scene that everything really sings. The action is intense and chaotic, the themes of men blindly destroying the last remnants of society in a flurry of violence not expressed shyly. And what follows is a journey through the young woman’s “home,” which is itself one of the more awe-inspiring settings in all of anime, its endless jugs of water laying in honor of a giant fossilized half-bird half-human being. It reads like the stream of conscience ramblings of a man on the brink of spiritual implosion, and to be honest, this new restoration kind of makes you believe it actually is. And it’s one of the great films ever made.

Some films end when the credits roll. Angel’s Egg continues long after, carried silently within the viewer, like a secret object whose fragility makes it no less essential.