Filmmaking, as in anything, even politics, is a collaborative effort. You have the director, the leader of the troops, the commander-in-chief, shall we say. Then there are the actors, players in the director’s show, and also men and women the filmmaker can bounce ideas off of, collaborate with, and ultimately help with his or hers vision making it to the big screen. And just like in politics, the more collaboration between the two parties, the more ultimately is achieved both palpably, and also creatively.

Then there is Lincoln. A film inherently about a man willing to go to any length to get his vision across, director Steven Spielberg gives us his vision of the iconic former President of these United States. However, with Daniel Day-Lewis as the man himself, the collaboration between star and director has ultimately turned this film into not only one of the director’s greatest films, but also one of the oddest and most esoteric entries into his legendary filmography.

Based on the book A Team Of Rivals, Lincoln focuses (much like a film like John Ford’s brilliant Young Mr. Lincoln) on a specific portion of this man’s life. With the Civil War still in full swing, we find Lincoln caught directly in the middle of a battle not only for the reconstitution of this nation, but also the decision to give all black men and women the freedom they so rightly deserve. Toss in the return of a son who is Hell bent on enlisting in the war and other issues at home, and you have a telling meditation on the life of a man who has since become both a myth and something more than any one single entity ever could. Today a symbol, Lincoln attempts to shine a light on the titular man as just that, a man and a politician.

And thankfully, it’s one of 2012’s greatest films, and arguably the best Steven Spielberg picture since Minority Report.

Penned by Tony Kushner off of the aforementioned Doris Kearns Goodwin-penned doorstop of a book, Lincoln‘s greatness comes from both the man in front of the camera, and the man behind it. Kushner’s screenplay screams stage play, and Spielberg has a field day with it. Giving the film over 100 speaking parts, this is far and away Spielberg’s most performance-driven piece of work to date, as well as being his most cinematically inspired. The film doesn’t rely on faux Hollywood melodrama lighting like a film like War Horse so heavily used or big gaudy action set pieces, but instead the film is allowed room to breathe within Spielberg’s lengthy takes and energetic dialogue interchanges. The filmmaker does allow himself a few flights of fancy, with swooping camera movements and a rustic frame that speaks volumes about he and Kushner’s respect for the subject matter and the era with which it is from.

Lush and palpable in its respect for the time period, the below the line aspects of this film are absolutely top-notch. John Williams’ score is beautifully and evocatively used, coming in at the exact moment you’d expect a Williams tune to pounce, but without every over-staying its welcome. Janusz Kaminski’s photography is awards worthy, giving us easily the most beautiful period photography in years. There are a few moments where you feel as though Spielberg’s appreciation for the films of John Ford comes in to play a little too much, where the gloss of Hollywood feels a bit over bearing, but Kaminski’s photography really suits this picture like a perfectly sized glove. Edited by Michael Kahn, the film is structured perfectly, where it’s two hour run time feels like an absolute breeze. Finally, Rick Carter’s production design and the costumes from Joanna Johnston are surefire Oscar locks, just the cream of this year’s crop in their departments.

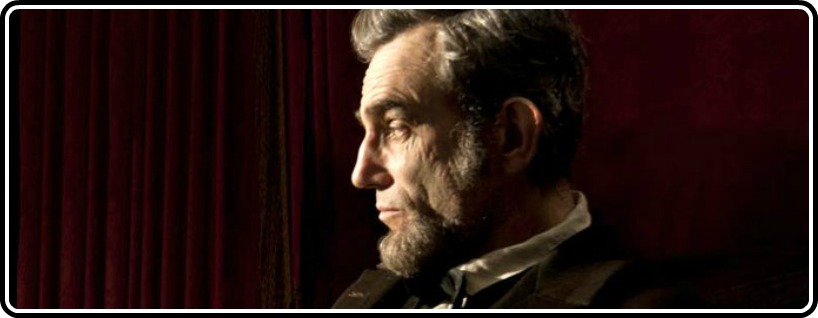

However, this is Daniel Day-Lewis’ world, we are all just lucky to live in it.

Yes, the voice may take a moment to get used to, but the brilliance of Day-Lewis’ turn is not that it is a larger-than-life, towering performance. It’s that there is a level of warmth, a level of fire and a level of human truth to the entire turn, that it feels like you are watching something truly special. Instead of simply a museum-level re-enactment style performance, Day-Lewis’ Lincoln is given so much heart and life through the eyes of the actor that it’s an absolutely show-stopping performance. Able to bounce around from a tone similar to that of a grandfather telling his young grandson a story to that of a leader lighting fire under the bottoms of his troops in a rousing speech at the drop of a hat, his performance is breathtaking. But that’s not the only brilliant turn this features.

Of the 100-plus speaking roles, every single performance is knocked out of the park. Sally Field plays Mary Todd, and her relationship with her husband is visceral. The pair have had their issues, but like any great and strong couple, they light a fire inside each other that is not seen anywhere else. Their relationship feels real, and it’s partially thanks to Field who truly has not been this good in ages. David Strathairn plays Lincoln’s right hand man William Seward, and his voice alone adds a level of gravitas to the political discussions he shares with the President. Joseph Gordon-Levitt is wasted but fine here as Robert Lincoln, and the likes of Hal Holbrook, Bruce McGill, Jared Harris and even Jackie Earle Haley pop up to give brief but fantastic performances. However, there are four supporting actors who shine above them all.

Playing comedic relief are Tim Blake Nelson, John Hawkes and James Spader, and all three are a breath of fresh air. For what should have been a rather stuffy meditation on the man who is Abraham Lincoln, to have these three play three men that can only be described as buffoonish lobbyists for the President with such hilarity really makes the film breeze by. Never allowing the film to lose its emotional and intellectual weight, the balancing act between the drama and the comedy is something that Spielberg has not really shown us much recently, but it’s absolutely thrilling here. Finally, Tommy Lee Jones sweeps the film up from under Day-Lewis’ feet, giving an almost career defining turn here as Thaddeus Stevens, the firesome anti-slavery supporter with a penchant for putting his foot in his mouth. Playing as almost a second emotional core for the film, Jones gives the film’s strongest performance, proving that while we may not see him a lot, he’s still more than got it.

Summed up perfectly by a line near the end of the film spoken by Jones’ character, Lincoln follows the story of how one of this nation’s greatest moments, the ending of slavery, was ‘passed by corruption,’ but ‘aided and abetted by the purest man in America.’ A meditation on Lincoln as that man, and not as the mountain of a myth he has since become, Lincoln gets yet another brilliant performance out of the best actor alive, Daniel Day-Lewis, while also finding director Steven Spielberg at his absolute best. Unlike any Steven Spielberg film prior, this is a passion project for the legendary director, and hopefully it marks the beginning of what may very well be the greatest period in the career of today’s biggest director.

1 comment