Susan Sontag famously wrote, “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art.” Those are good words to keep in mind when one considers Holy Motors, the rare beast that stands apart from such classical modes of viewing (and creation) like “intent,” “meaning,” or worst of all the persistent question, “what was this filmmaker trying to say?”

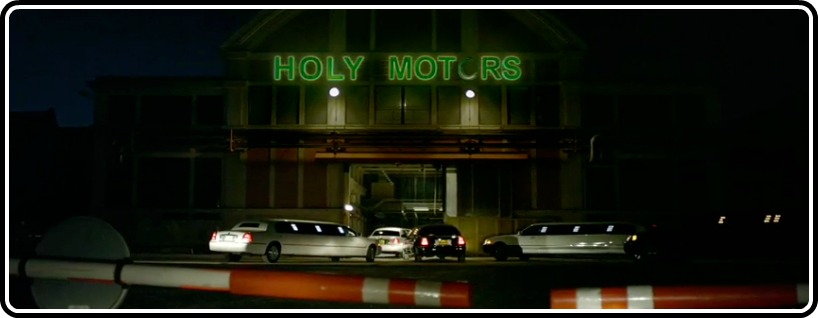

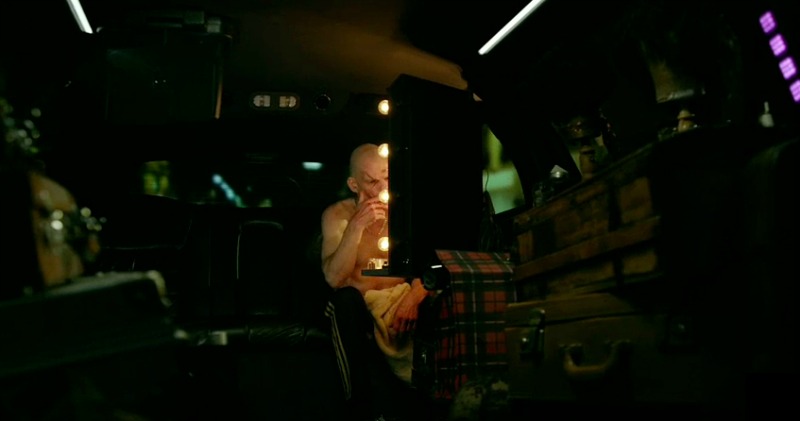

This is not to imply Leos Carax didn’t have anything on his mind when unleashing Holy Motors, but rather that his insistence on such notions is suitably buried, preferring instead to simply express and present something unto itself. So, sure, Holy Motors is “about” a guy named Oscar (Denis Lavant) who receives a series of assignments wherein he transforms into one character or another and performs in public, sometimes at a relative remove, but more often as an aggressive part of, and force to, his surroundings. The extent to which the people around him are “in” on his performance is at first the sort of thing you’d never question, but then becomes wholly more complex.

The result can feel episodic, leaving some sections exhilarating and others a little dull in a certain moment-to-moment sense, but the cumulative effect is surprisingly cohesive, even if it takes one a little while to truly start to feel it. For myself, it took nearly a week before the totality of the thing hit me and all its eccentricity started to cohere into something I not only “respected,” but truly loved. Because of the nature of its structure, Carax is given license to do almost anything, and the earlier sections take this and run, towards some incredibly off-putting material, pointedly daring the audience to hang with him. As this gives way to more poignant material, it becomes clear that Oscar’s performances are as much a part of himself as they are fabrications.

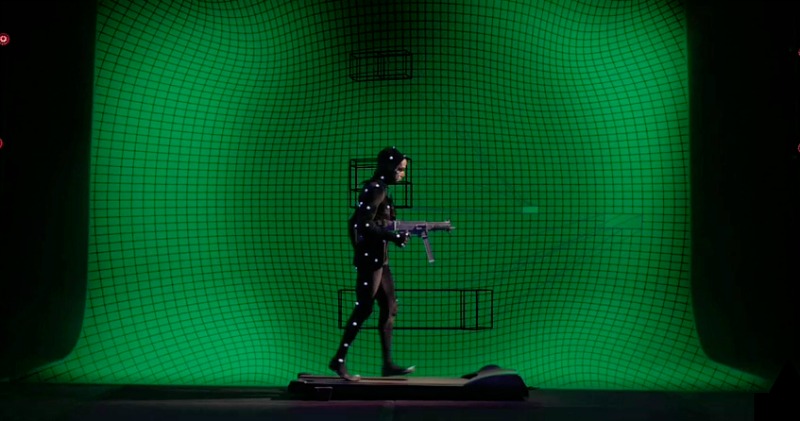

Holy Motors is not the kind of film one would say came from an “actor’s director” (though Lavant gives one of the best performances of the year in it), yet it is a remarkable tribute to the art of acting, which requires one to live at least part of one’s life in the public space. I always find it remarkable, particularly at the theatre, that we are given such open access to the way somebody is living for a set period of time, and it’s the rare form that makes public the act of creation. One can write or paint in total privacy, direct a film in relatively controlled circumstances, but to act, one must live part of one’s life in public.

In the context of the film, there are hints that Oscar’s performances are being filmed in some way by tiny, unseeable cameras, as his mourns the days when the presence of a camera was obvious. In this way – bolstered somewhat by Carax’s finance-driven decision to shoot the film digitally – the movie is something of a wake for celluloid while also the baptism of the new, digital era.

Lavant grounds Carax’s mystery with surprising humanity. Actors call upon themselves as much as the world around them, and each stop reveals something new about Oscar. Or perhaps nothing at all. In one iteration, we dip into what appears to be Oscar’s “true” home life (he begins the day with one family and ends it with another, so who really knows), but even that could simply be another assignment. Given the sheer breadth of what he’s asked to do (the numerous roles that Cloud Atlas asks of its cast is nothing compared to what’s on display here), simply achieving what each assignment demands would be something extraordinary; than he makes it all congeal is something else altogether.

To discuss much further would be to spoil the joy of discovery, and besides, the film is so infinitely mysterious that one could come up with perhaps infinite readings of the film that would all be equally valuable. I know there are many who would reject this sort of opacity, but even if we can’t totally deduce what Carax is up to here, I have little doubt that he knows. Besides, the experience of watching the film is so singular, so often captivating, and certainly intriguing that to bemoan its disinterest in summarizing its “themes” would be akin to leveling the same charge at Stan Brakhage’s Untitled (For Marilyn). It’s the rare film that doesn’t feel the need to be “about” anything, but simply is something. At turns hilarious, transcendent, tragic, and terrifying, Holy Motors is indeed, quite something.