Neruda is the second of two extremely blunt biopics directed by Pablo Larraín to be released in the U.S. this month. Like his more-visible Jackie, it openly discusses all of its themes in a free-form, non-linear editing scheme that diminishes plot while elevating mood and ideas. While Jackie unfolds with a level of grace that lets its endless discuss of society’s approach to beauty, fame, power, and women’s roles only start to wear by the end, Neruda is exhausting within its first ten minutes. To be fair, it has considerably more exposition to deliver, dealing with an episode in the life of a Chilean writer and senator that most audiences won’t be familiar with (contrasted with Jackie, which is about one of the most famous incidents of the 20th century), but the thorny backstory is only the beginning of Neruda’s endless series of complications, inventions, and speculations.

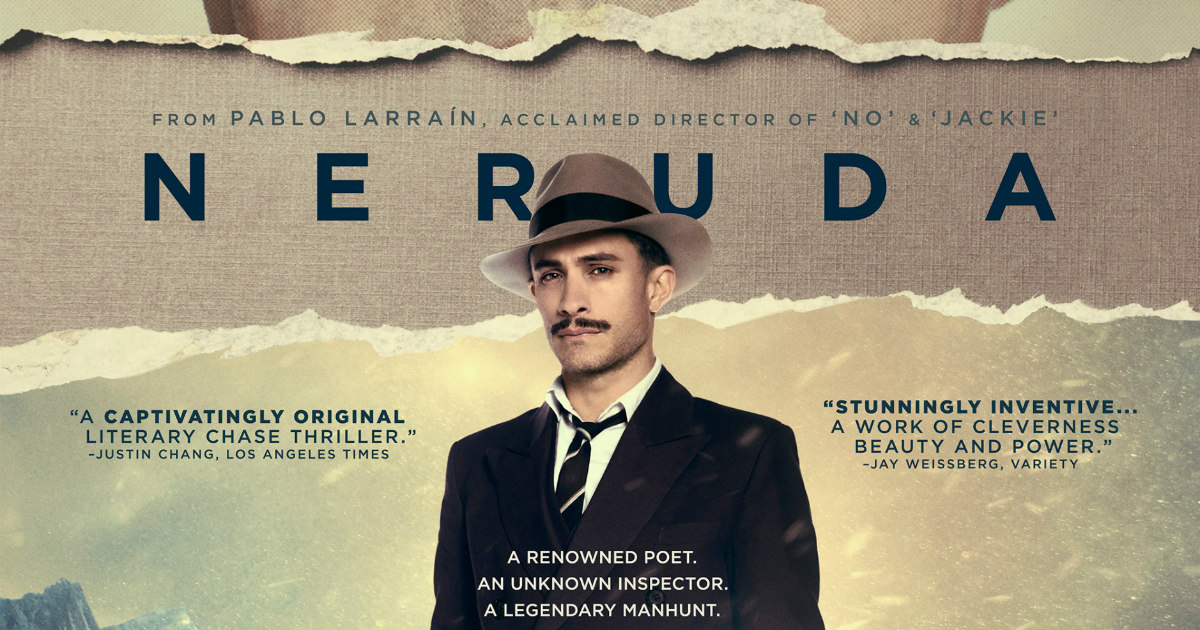

Here are the facts of the case – in 1945, poet and diplomat Pablo Neruda was elected to the Chilean senate, representing the Communist Party of Chile. But as the world stage turned against communism, Neruda became a minority figure, and in 1948, Chilean President González Videla outlawed the party and issued a warrant for Neruda’s arrest. He went into hiding for a year, then exile. Neruda casts Luis Gnecco as the bombastic public figure, who finds friends easily in the Chilean underground and even manages to have a bit of fun among their ranks. It also casts Gael García Bernal as Oscar Peluchoneau, a policeman determined to apprehend Neruda. Now, Peluchoneau really did exist. Whether he single-handedly chased Neruda across the country is less likely. That the character Bernal plays ultimately ends up questioning his very existence practically does the rest of the work for you.

On top of all that, Larraín cuts up the conversations in the model of The Limey, starting them in one place, continuing in another, possibly finishing in a third or fourth or fifth or who can even keep track anymore. No doubt the point is to disorient the viewer, further question the line between fact and fiction and create the sort of mindset in which someone of Neruda’s intelligence and creativity must have been. When the creative brain is turned against itself in the course of an actual manhunt, the potential threats are innumerable. Larraín’s strategy in replicating it similarly suggests there is no “right” interpretation, only a sense of dislocation and unease. It all proves a bit too much for the film to get a handle on. Larraín is an energetic director, eager to play with the physical demands of cinema by removing traditional barriers in lighting, blocking, eyeline rules, etc. Again, this work in Jackie – they shot on film, and the physicality of the production is immediately obvious. Neruda, which was shot digitally and employs rear-projection and other manners of artificiality, never conveys the same hurdles. The digital camera can be anywhere; limitations feel nonexistent. The decision to force those barriers over feel more like a bother than a thrill.

Gnecco and Bernal effectively drive home the central tonal conceit, that the left-wing in Chile is a fun-loving bunch dedicated to their fellow citizens while the right is authoritarian and hard-lined. As with many films that limit the interaction between their central players, the showdown between the two of them takes awhile to feel pertinent. Larraín plays with this somewhat by suggesting Oscar might be more an invention of Neruda’s self-aggrandizement than a genuine threat, which sort of makes them both part of a portrait of the poet, but by that point we’re too lost in a swarm of politics and “just what is storytelling, man” pontification to reconcile it all.