Flipping through my complete set of Eclipse Series DVDs for this week’s review, I selected a film with a central premise that seems rather timely. A young child is caught stealing a few coins from his family’s modest cash-on-hand, and as a punishment is sent to bed without supper. But the meal his father deprived him turns out to be poisonous, killing everyone else in his family! The boy internalizes from this unfortunate event the lesson that dishonest behavior sometimes reaps abundant rewards.

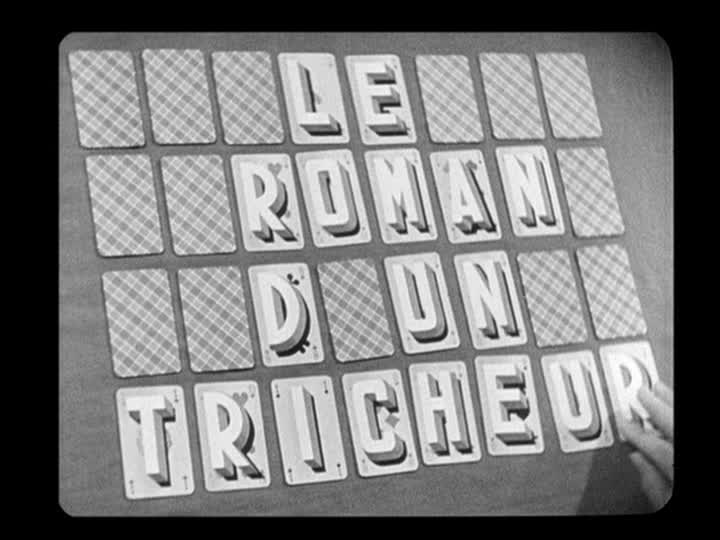

From this formative episode, he goes on to become a master of the art of deception, using benign manners, glib smooth talk, an impressive ability to disguise himself convincingly and well-rehearsed sleight of hand to win the trust of naive strangers. Those he allows into his inner circle come to recognize his manipulative skills but keep the secret quiet in order to profit from it themselves. He finds his path through life made easy through the confidence placed in him to handle large sums of other people’s money, and manages to evade the harsher sort of consequences that would befall most of us if we conducted ourselves as recklessly as he does. In short, the perfect kind of film to help me clarify the situation as I choose which politicians to vote for, since tomorrow is Election Day here in the USA. It’s The Story of a Cheat, from Eclipse Series 23: Presenting Sacha Guitry.

I guess I should make it clear that The Story of a Cheat is not really about a career in politics per se, but I attribute that as having to do mainly with Monsieur Guitry’s apparent lack of interest in the job as opposed to his lack of qualifications. For he is a rather charming and persuasive speaker, one who’s accustomed to holding his audience willingly captive as he spins his cleverly worded, seductively phrased and somewhat long-winded tales. This early (1936) talkie is perfectly suited to the Eclipse Series mission of “lost, forgotten or overshadowed classics,” for Guitry’s films fit each of those categories. Once upon a time, he was a literary and theatrical superstar in France. Son of a prominent stage actor, he made his showbiz debut at age 5 and grew up to become one of the most prominent and prolific comedic playwrights of the 1920s, scripting over 120 plays and 30 books.

Preferring the dynamics of live performance over the emerging medium of film, Guitry was at first very reluctant to get involved in cinema, even criticizing it rather bluntly before having a change heart several years later as he realized the potential for him to reach a larger audience on the screen. His greatest achievements on film were produced in France during the late 1930s, a golden age of sorts according to some cinephiles (and count me among them) when directors like Jean Renoir, Marcel Carne, Julien Duvivier and others were developing distinctly French subgenres like poetic realism, a precursor to film noir that placed timelessly tragic themes into rough-hewn working class settings. The works of Guitry, who without his old man make-up or other disguises bears more than a passing resemblance to the iconic French actor Jean Gabin, put him in somewhat wealthier, more fanciful and escapist surroundings, but they carry that same touch of elegant resignation and fatalistic bemusement that make films from that era so uniquely charming and enjoyable.

But Guitry’s reputation took a major hit during the Nazi occupation of France, as he was seen (with ample justification) as a too-willing collaborator with the German authorities in order to keep his comfortable celebrity lifestyle intact. Indeed, Guitry proved to be outright sympathetic to Marshall Petain, head of the Vichy Government that served as the Nazi proxy until France was liberated by the Allies in 1944, and was eventually arrested and imprisoned after the war for the offense. Though he eventually returned to writing, acting and directing movies into the 1950s, he never regained the level of admiration that he’d attained prior to 1940. In a sense, the same malleable ethics that he put on such humorous display in The Story of a Cheat did come back to haunt him when the situation in France took a turn to the much more serious.

Be that as it may, Guitry’s fall from grace, both politically and culturally, may explain why relatively few of us Criterion fans had ever heard much about him last spring when this new Eclipse set was announced, but I’m personally quite glad to have discovered it. Ideological and character considerations aside, Guitry turns out to be quite a suave and engaging bon vivant as he basically gives us an illustrated monologue. He tells his fictional life story in retrospect, sitting down at a cafe one afternoon to write out his memoirs, pausing occasionally to interact with his waiter and customers seated near his table. The flashback structure, now familiar to us in so many films that have used it over the decades, was innovative at the time, perhaps even the earliest example of its use in film, from what I read on French Wikipedia. However that debate is resolved, the off-screen narrator technique is used creatively to incorporate an intriguing variety of filmic elements that still seem fresh, even experimental, in the way that Guitry assembled them:

- light comedy sketches of late 19th century village life when his unnamed character was a young boy

- episodes of misadventure as he’s abducted by a greedy relative and his horrid wife, then runs away to become a bellboy at upscale restaurants and hotels frequented by the wealthier members of the bourgeoisie

- a subplot involving an anarchist conspiracy to assassinate Czar Nicholas, featuring vintage film clips of the czar and his entourage from his 1896 visit to Paris and the brief appearance of a young and dark-haired Roger Duchesne, best remembered now for his immortal role as Bob le flambeur (true to form, the conspirators even hatch their scheme in Montmartre)

- a brief musical performance, set in a brother frequented by soldiers, by Frehel, a plump matronly singer who was quite popular at the time and performed a similar bit in Duvivier’s Pepe le Moko

- documentary-like footage of the geography, architecture and cosmopolitan history of Monaco

That last feature, along with the extended scenes set in a casino at the end of the film, where le tricheur works as a croupier at the roulette table, makes The Story of a Cheat a nice companion piece to Ernst Lubistch’s Monte Carlo, one of the earliest titles I featured in this series of reviews. Nowadays it’s easy to take legalized high stakes gambling and all its glamorous accouterments for granted but the two films offer a nice glimpse of an era when the mere thought of a night in Monte Carlo conjured up fantasies of the liveliest, most stylishly refined diversions attainable, for those fortunate enough to find themselves in its rarefied environment. Even with casino action so ubiquitous to the point of overkill in our times, there’s something quite delightful to me about watching old clips of that classic aristocrat’s playground set squarely in the middle of Monte Carlo, the glittering “pearl in the crown” of the French Riviera (oops, that’s a different movie…)

Though my comments to this point have focused mainly on how The Story of a Cheat recounts its lead character’s financial swindles, cheating of the relational sort is involved as well, in a series of running gags that cover all the stages of a man’s amorous life, from the fleeting excitement of one’s first sexual encounter with a frisky countess to the entanglements of wife and mistress and the conflicting emotions that attach themselves to each woman, all kindred cheating spirits in their own way. (Guitry married five times over the course of his life, and seemed quite susceptible to the sultry feminine stare, so I suppose he drew from abundant experiences in scripting this portion of his tale.) For the most part, the lessons gleaned from his encounters are more frothy and ephemeral than profound, and I don’t feel much inclined to spell them out here. See and enjoy them for yourself!

My hunch is that most who read this have yet to see The Story of a Cheat, and if you think this is the kind of film you’d enjoy, I’d rather preserve the element of surprise. Just keep a close eye on the lead character – second and third viewings reveal a lot of droll subtleties that you might miss the first time around. Even those who have seen the film probably regard it as a tasty bonbon rather than a substantive meal, which is a perfectly fine thing to enjoy! Guitry himself offered it to us as such, an effervescent and seemingly effortless (but really, quite brilliantly executed) reminiscence, aimed primarily to amuse and prompt knowing nods of recognition from his worldly-wise audience. To the degree that The Story of a Cheat instructs and moves us to correct our course, I suppose it serves a constructive social purpose. But my experience is that characters dedicated to using deceptive means to garner easy riches and the appearance of success are too committed to such pursuits for a mere movie to significantly affect their choices. As the film’s lead character demonstrates, life has to hit them upside the head a lot harder than that with real-world calamities before sufficient motivation is found to change their ways and make honest gamblers of ’em.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

Very nice write up again, Dave. Wonderful, underrated director!