Last week on my Criterion Reflections blog, I published a review of Le Notti Bianche, Luchino Visconti’s 1957 adaptation of a short story by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Through another of the curious synchronicities forged by my chronological scheme, the next film in that queue is another cross-cultural interpretation of Russian literary source material, Akira Kurosawa’s version of The Lower Depths, based on a play by Maxim Gorky.

So when it comes to this week’s Eclipse review, which I generally write between installments on my personal site, there’s simply no better option to connect those two films than a Kurosawa take on a Dostoevsky original! Just don’t assume that, if I give you an elbow nudge and say “hey, take a look at that idiot,” that I’m being rude or making fun of someone. No, in this instance, I’m simply directing your attention to one of the most unusual entries in the vast filmography of a great man. It’s The Idiot, from Eclipse Series 7: Postwar Kurosawa.

Even though The Idiot was filmed and released directly between two of Kurosawa’s most widely appreciated masterpieces, Rashomon and Ikiru, it’s nowhere near as famous or revered.

Given the phenomenal power and success of those two films, quite different in setting and tone, one can’t be faulted for approaching The Idiot eagerly, to see what splendors are found therein. However, The Idiot is less renowned for a reason – it’s one of Kurosawa’s most troubled projects and gives plenty of indication that he was still at a point in his career where his ambitions exceeded his grasp.

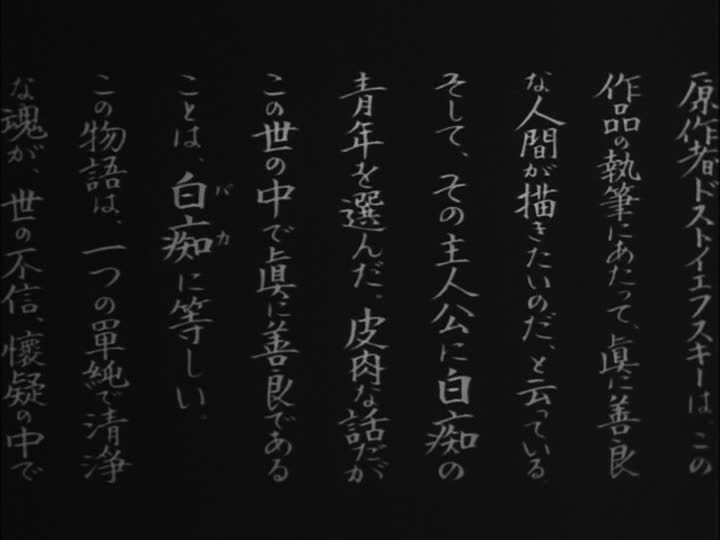

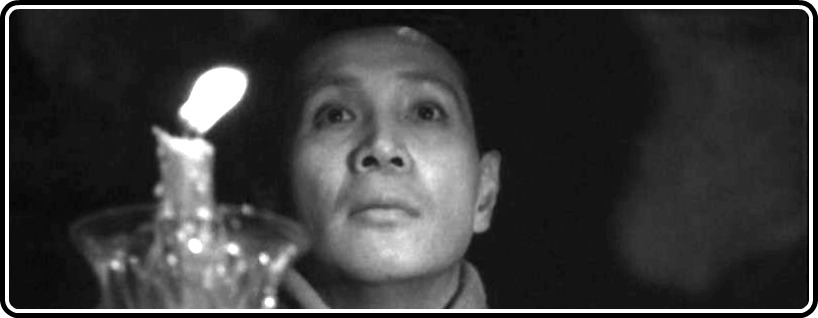

The “idiot” referred to in the title is Kameda, a soldier whose life had been spared just moments before he was to face a military firing squad. Though given a reprieve when all seemed lost, the stress overwhelmed the poor innocent man, triggering a series of epileptic seizures that transformed his personality. Whatever Kameda was like in his personal interactions before, from that point on he was perpetually wide-eyed, hyper-sensitive, childlike in his simplicity and innocence, and painfully slow on the uptake to common social cues.

He spoke whatever was on his mind, and possessed an unerring insight into the hidden depths of the people around him. In short, Kameda is a guileless soul, pure of heart, easy to exploit but unnervingly profound in his ability to push aside the veil of petty deceits and customs typically used to manage affairs in respectable society.

As Kameda travels from a prison camp on the southern island of Okinawa to the northernmost island in Japan, Hokkaido, he makes the acquaintance of Akama, the rebellious son of a rich family. Akama, realizing that there’s something “special” about Kameda, tells his new friend about Taeko, a beautiful woman that he is eager to reunite with. Upon seeing her portrait displayed in the window of a photographer’s studio, Kameda has an epiphany as he stares deeply into the image.

He detects in her intense, commanding gaze a nobility and desperations that transfixes him, creating a destiny-altering bond even though they have yet to meet in person. As it turns out, their paths will cross soon enough. (Let me mention here that Akama is played by Toshiro Mifune and Taeko is played by Setsuko Hara. If the mere mention of those two names doesn’t automatically crank up your interest in this film, go back for a refresher in Japanese Cinema 101 before bothering to read much further…)

Kameda, the idiot, moves in with the family of his sole living relative Ono (Takashi Shimura, another giant among postwar Japanese actors, though he’s merely a side player here.) Ono has an employee, Kayama, who’s agreed in principle to marry Taeko, who we learn has been a “kept woman” (basically, a concubine) of a wealthy man who now intends to get some distance from her tainted reputation.

Because she’s viewed as so much damaged goods by the eligible men of Hokkaido, a payment of 600,000 yen has been promised to Kayama as compensation for the risk and embarrassment he’ll suffer.

The deal still hinges on Taeko’s agreement, and when she visits her betrothed, that’s when the fateful encounter between her and Kameda, and then, shockingly, Kayama and the intruding, boastful Akama, unfolds. It’s the first of several dramatically super-charged showdowns, each brilliantly shot and edited by Kurosawa and bearing his distinctive touch for creating pivotal “all or nothing” moments. In this one, we learn that Taeko is unwilling to yield easily to anyone’s plans for a convenient transfer of her services.

She’s understandably embittered by the abuse she’s suffered, and also aware of the power of attraction she holds over the men who desire her despite the scandal that comes with her acquaintance. Determined to take full advantage of her rare position of control over the situation, Taeko skillfully inflicts her own share of torments on the men pressing in on her, cackling with maniacal glee as she relishes each moment of revenge… until Kameda’s innocence finds its way through the protective barriers that Taeko has erected around herself and wins her heart.

If the entanglements I’ve described so far haven’t confused you yet, I suppose you’re ready to handle the introduction of another pivotal character, Ayako, Ono’s daughter and the female rival to the imperious Taeko. Ayako is more of the girl next door type, a modest but still temperamental young woman who gradually takes an interest in Kameda (apparently their family relationship is not so close as to forbid an eventual marriage.) Thus we wind up with a knotty thicket of relationships and rivalries that practically require a flow-chart to keep straight as we move into The Idiot‘s riveting conclusion. Here’s how it lays out in bullet points:

- Kameda loves Taeko, though his feelings are based more on a first impression than on actually knowing her

- Kayama loves Ayako, his boss’s daughter, but is drawn to the wealth that would come from marry Taeko

- Taeko loves Kameda, but realizes that his pure heart would be destroyed if they consummated the relationship, so instead she chooses the thuggish Akama, the only kind of man she considers herself worthy to live with

- Akama desires Taeko for the sake of lust and control, but knows that she really loves Kameda, which provokes his jealousy

- Ayako loves Kameda but recognizes Kameda’s obvious yearning for Taeko

- Kameda develops an attachment to Ayako based on fondness, admiration, loyalty and circumstance

As tedious as this synopsis may read, I think it provides a helpful primer for anyone viewing The Idiot for the first time. The density of the plot, some awkward edits (explained in part below) and the drawn out tempo make this film more difficult to access than the fast-paced, exciting adventures that most of us immediately think of when Kurosawa’s name is mentioned.

I’ve watched The Idiot three times this week and now consider myself sufficiently prepped to appreciate the interplay of various character types, meditations on the struggles between spirituality and materialism and numerous creative subtleties packed into what survives of the film. But that’s a unique advantage that comes with living in the DVD era. Here’s a very short and delicate fan edit of several moments from The Idiot that may give you a sense of the foreboding (and snowy!) atmosphere it conjures up.

According to Kurosawa himself, filming The Idiot had been a longstanding ambition of his, preceding his plans to shoot Rashomon. When that film started to rack up the awards and international acclaim, Shochiku Studios gave the young director a green light on the daunting task of filming one of those archetypal sprawling Russian novels. Granted, The Idiot is no War and Peace – it generally prints up at “only” between 600- 700 pages – but it’s a big ol’ brick of a book in any case. And in its original cut, which sadly no longer exists, Kurosawa’s adaptation was just as massive, with a running time of nearly 4 1/2 hours.

The full version’s first screening drew such a mediocre response that the studio demanded 100 minutes of cuts, to whittle it down to a more manageable 2 hours and 46 minutes. That’s still a long movie, but with Kurosawa’s intention of telling nearly the whole story of the novel, transposed to a postwar Japanese setting, it’s easy to imagine the narrative gaps that resulted when huge chunks of the film were left on the cutting room floor. And those gaps are quite apparent, especially in the movie’s first half, where long scrolling intertitles and expository narration are used to connect scenes that otherwise wouldn’t flow together.

As easy as it is to dump our anger on faceless studio chiefs who care nothing about art and focus only on the financial bottom line, I can understand why they pushed Kurosawa to trim it down to more conventional length. The story takes a long time to get casual viewers fully engaged, and if the current conclusion of Part I was supposed to serve as the ending of the first film of a two-part series, I think a lot of audience members wouldn’t have bothered coming back the next night, or even after the intermission.

In an era when phrases like “TV mini-series” or “home video sales” meant absolutely nothing, putting bodies in the seats was the only way to recoup the investment. And The Idiot, despite some extraordinarily fascinating aspects of great interest to Kurosawa fans today, was probably just too slow-moving and high-brow literary for the average Japanese film-goer of 1951.

Even so, I think The Idiot is a film that should be actively sought out by anyone eager to see:

… a different side of Setsuko Hara than the saintly virtuous Noriko she’s best known for in Ozu’s Late Spring, Early Summer and Tokyo Story;

… a young Toshiro Mifune, looking about as cool and rowdy as ever, just on the verge of his emergence into major stardom;

… most significantly, a project that was dear to and expressive of the heart of Akira Kurosawa, filled with unique passages like the “Night on Bald Mountain” ice festival and Kameda’s paranoid wanderings through the snowscapes of urban Hokkaido.

The Idiot‘s focus on a lead character with whom Kurosawa identified deeply and personally sheds much light on his artistic vision. It’s fair to conclude that, with the commercial failure of this film, Kurosawa had no other choice but to hone his craft with greater concern for popular tastes.

The fact that he was able to rebound with films as innovative and memorable as Ikiru andSeven Samurai is a testament to his genius. But it may be The Idiot, even in its truncated form, that offers the clearest example of a Kurosawa “labor of love.”

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

1 comment